-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Muhammad Imran Aumeerally, A puzzling pelvic passenger: case report of a wandering splenunculus, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 10, October 2025, rjaf841, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf841

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A pelvic accessory spleen is a rare congenital anomaly. The majority of accessory spleens are found at the splenic hilum. This unusual localization may result in diagnostic uncertainty and may be an exceedingly rare cause of pelvic pain. This article reports the case of an accessory spleen presenting as a symptomatic left adnexal mass. The mass was removed laparoscopically and histological assessment revealed the mass to be an accessory spleen. An accessory spleen is not uncommon and would be of no clinical concern in the vast majority of patients. However, a pelvic accessory spleen is a rare condition and its presence can confound the typical differential diagnosis for pelvic pain. While a pelvic accessory spleen is not a typical cause of pelvic pain, this case report teaches the value of a broad differential diagnosis and continuing further investigations when there remains diagnostic uncertainty.

Introduction

An ‘accessory spleen’ describes splenic tissue found in ectopic locations and is found in an estimated 10%–30% of the general population [1]. Accessory spleens are typically found in the splenic hilum, tail of the pancreas, or omentum [2]. This article presents a case of symptomatic pelvic accessory spleen in a patient who was being investigated for infertility. This case report has been reported in line with the Surgical Case Report (SCARE) guidelines [3].

Case report

A 36-year-old female presented to the obstetrics and gynaecology (O&G) outreach clinic of a rural Australian hospital in March 2022. She was referred from her general practitioner (GP) with primary infertility and the sonographic finding of a 5 cm left adnexal mass.

Her primary concern was the inability to fall pregnant despite active attempts over the past 12 months. She had an associated history of intermittent left-sided pelvic pain over the past 6 months which would last several minutes to hours before resolving spontaneously.

She had a background of regular periods and no dysmennorrhoea. She would occasionally report some mid-cycle pain. She did not experience dyspareunia. She had no previous history of sexually transmitted illness. Her last cervical screening test was performed in 2019.

The patient had no significant past medical history. Her surgical history was notable for a diagnostic laparoscopy performed in Hong Kong in 2010 for the removal of an ovarian cyst.

Her abdominal examination did not reveal any palpable masses nor did it illicit any tenderness. Speculum and vaginal examinations were also unremarkable.

Laboratory investigations were unremarkable, including haemoglobin, haematocrit, platelet count, and a routine biochemistry panel. Tumour markers, including CA-125 and CA-19.9, were normal.

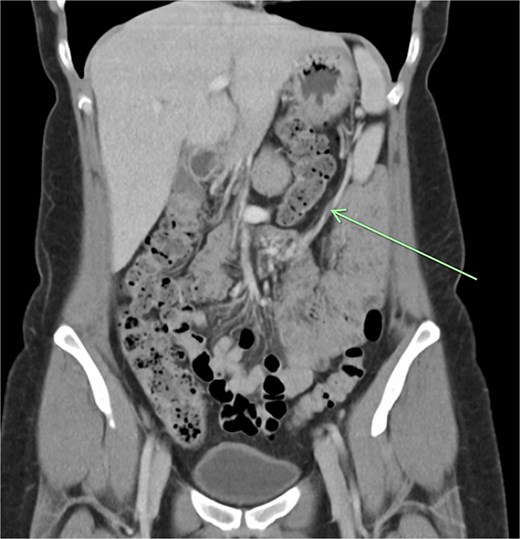

Transvaginal ultrasound demonstrated a large solid vascular mass in the left adnexa measuring 50 × 52 × 54 mm separate to the left ovary. Sonographic appearances of the uterus, endometrium, ovaries, kidneys, and bladder were reported as normal. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a solid rounded lesion with moderate enhancement measuring up to 55 mm. This lesion was reported as most likely to represent a broad ligament or pedunculated fibroid.

The patient underwent an elective diagnostic laparoscopy under general anaesthesia. The uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes, and the pouch of Douglas all appeared normal. A dye test was performed and found the fallopian tubes to be patent. Importantly, no lesion consistent with the preoperative imaging was identified within the pelvis.

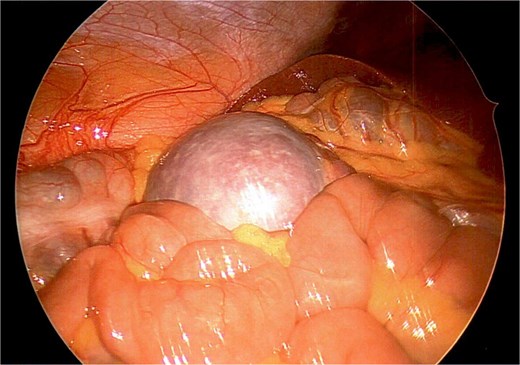

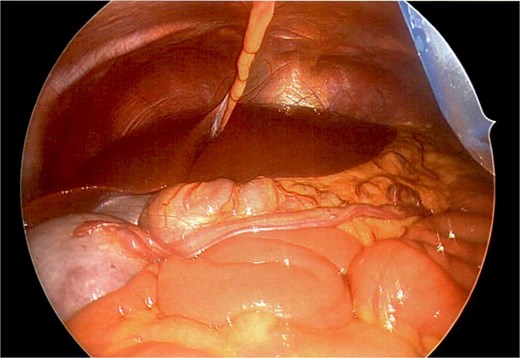

A firm solid well-circumscribed 6 cm lesion was identified in the right upper quadrant. The general surgery team was contacted for intraoperative consultation. This lesion appeared to be mobile and attached to a long vascular pedicle which was followed to the left upper quadrant, where it passed over the transverse colon towards the splenic hilum (Figs 1 and 2).

Wandering accessory spleen located in right upper quadrant with patient in Trendelenburg position.

Long vascular pedicle of accessory spleen leading to left upper quadrant.

The aforementioned CT was reassessed intraoperatively together with this new information. The vascular pedicle was traced from the lesion towards the splenic vessels at the tail of the pancreas. A normal spleen was identified in the left upper quadrant (Figs 3–5). The overall impression was that this lesion represented accessory splenic tissue. The general surgery team called the patient’s next of kin, who gave consent to proceed with an excision of this wandering accessory spleen.

Long vascular pedicle leading to accessory spleen in the pelvis.

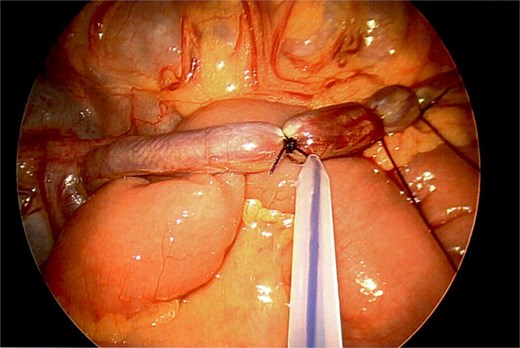

The vascular pedicle was secured as proximally as possible in the left upper quadrant using three PDS Endoloop ligatures (Ethicon) between which the pedicle was divided using scissors leaving two Endoloop ligatures on the remnant stump (Fig. 6). The lesion was placed in an Endo Catch specimen retrieval pouch (Medtronic) and then retrieved through a small Pfannenstiel incision (Fig. 7).

On follow-up telephone appointments with the general surgery and O&G teams, the patient reported that her intermittent pelvic pain had resolved. The histology of the vascular lesion confirmed the removal of an accessory spleen. Ultimately, the patient would fall pregnant within the next 6 months and give birth to her first child the following year.

Discussion

The spleen is a foregut-associated structure located under the diaphragm in the left upper quadrant of the abdominal cavity. While it is not a direct derivative of the foregut, it shares the same blood supply as the foregut-derived organs – the coeliac axis. The spleen develops from the mesenchyme in the dorsal mesogastrium as a condensation of these cells. As a result of this embryogenic process, it is susceptible to the development of accessory spleens, wandering spleen, and polysplenia.

The pelvic accessory spleen is considered a very rare entity. A meta-analysis by Vikse et al. reviewed the prevalence of accessory spleens and found the overall incidence to be 14.5% [2]. The meta-analysis grouped all rare sites of accessory spleens (left paracolic space, upper pole of left kidney, left hypochondrium, and pelvis) together with a pooled prevalence estimate of 5.4%. A study by Unver Dogan et al. reviewed 720 autopsy cases, identifying two pelvic accessory spleens – <0.3% [3].

There are currently nine reported cases of splenectomy of a pelvic accessory spleen. Most of these pelvic accessory spleens present with torsion, while others were incidentally identified [1, 4–7]. A publication by Taskin et al. reported a similar case of symptomatic pelvic accessory spleen, which was ultimately removed by laparotomy.

The management of a wandering accessory spleen should depend on whether it has been symptomatic or on the likelihood that it may cause future symptoms. This can be based on the mobility of the accessory spleen along a long vascular pedicle, which places it at risk of torsion or of causing bowel obstruction.

It is probable that in our case report the wandering accessory spleen was symptomatic given the presence of pelvic pain prior to and the absence of pain following surgical removal of the lesion. This intermittent pain may have been due to the repeated torsion and detorsion of the accessory spleen around its long vascular pedicle.

Conclusion

Given the rare nature of this phenomenon, a wandering accessory spleen should not be the primary consideration in the work-up of a pelvic mass, although it should be included in an extended differential diagnosis. The treatment of a pelvic accessory spleen should be guided by symptoms or the likelihood of future risk.

Conflict of interest statement

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

There was no grant or financial support for this case report. There are no financial contributions to disclose.

Patient consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and the accompanying deidentified images.