-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Utku Kubilay, Canberk Kertmen, Orçun Delice, CT navigation-assisted intraoral extraction of large submandibular gland stones: a minimally invasive approach, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 1, January 2025, rjae832, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae832

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Sialolithiasis is a common cause of salivary gland obstruction, leading to symptoms such as pain and swelling. In cases of intraparenchymal submandibular stones and proximal ductal stones larger than 7 mm, interventional sialendoscopy may fail, necessitating sialoadenectomy. As an alternative, intraoral stone extraction can be performed with CT-guided navigation. This case report describes a 52-year-old male with previous sialadenitis complaints. Imaging confirmed a fixed intraparenchymal stone measuring 21 × 18 mm. Using CT navigation, the stone was located and removed intraorally. Salivary flow resumed through Wharton’s duct on the same day postoperatively and the patient was discharged without further complaints or new stone formation during a 1-year follow-up. This minimally invasive method, utilizing CT navigation, allows for the preservation and functional recovery of the submandibular gland, avoiding skin scarring and reducing the risk of nerve damage.

Introduction

The submandibular gland is particularly prone to sialolithiasis due to the viscosity of the secretions and the upward trajectory of the Wharton duct [1]. Although most stones form within the duct, a significant proportion can be found within the gland parenchyma [2]. Minimally invasive techniques, such as interventional sialendoscopy with or without extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL), have shown efficacy in managing intraductal stones smaller than 7 mm. However, for proximally located intraparenchymal and intraductal stones larger than 7 mm, these methods may not always be feasible. Traditionally, these stones often require gland excision, which carries risks of nerve damage and cosmetic concerns.

Intraoperative CT navigation provides a detailed anatomical map, enabling precise targeting and extraction of these stones with minimally invasive techniques.

Case presentation

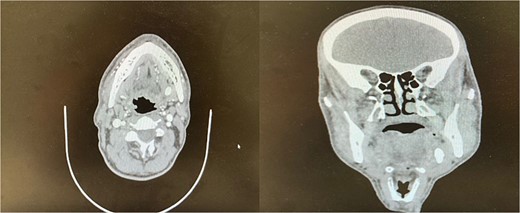

A 52-year-old male presented with a history of recurrent pain and swelling in the left submandibular region, suggesting sialadenitis. Ultrasound (US) identified a deeply located glandular stone measuring 2 cm. Subsequent CT confirmed the presence of a 21 × 18 mm fixed stone located deep within the gland parenchyma (Fig. 1).

Preoperative coronal and axial CT images showing a sialolith within the submandibular gland.

A navigation system (Fiagon, Hennigsdorf, Germany) was used during the surgery. The patient was positioned supine with the head stabilized to replicate the alignment of the preoperative imaging. Surface registration was performed by matching stable anatomical landmarks, including the hard palate, alveolar ridge, and gingiva, using the CT navigation system (Fiagon, Hennigsdorf, Germany).

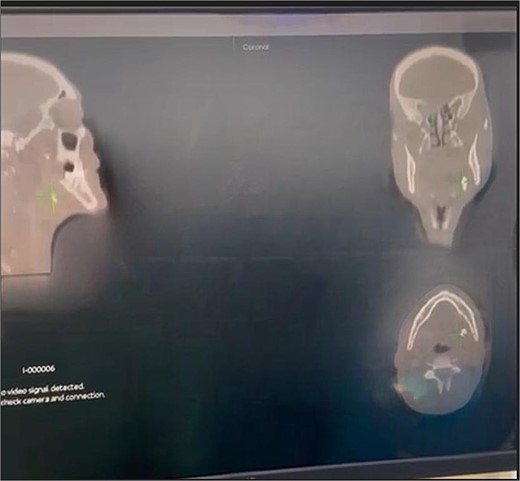

The accuracy of navigation was periodically verified by referencing stable bony landmarks, such as the mental foramen and mandibular condyles, with the navigation probe. Realignment was conducted as needed to ensure consistent anatomical mapping and precise localization of the submandibular stone (Fig. 2). After surface registration, a 1 cm mucosal incision was made intraorally at the nearest point indicated by the navigation pointer, parallel to the anticipated course of the Wharton duct. Blunt dissection was performed to expose the duct, with navigation toward the stone guided by the system. Great care was taken to protect the lingual nerve throughout the procedure. The depth of dissection was gradually advanced by periodically verifying the position with the navigation pointer probe (Fiagon) to maintain precision. During dissection, the stone was accurately located within the gland parenchyma using real-time visualization, and it became palpable, distinguished by its unique color and texture (Fig. 3). The stone was fragmented and removed in pieces because it was fixed (Fig. 4). The surgical field was flushed with saline to remove any residual stone debris, and the incision was closed with 4/0 Vicryl, which is an absorbable suture.

Intraoperative navigation identifying the location of the sialolith.

Intraoral extraction of the submandibular gland stone during the procedure.

Fragments of the submandibular gland stone extracted during surgery.

Postoperative care included a 7-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanate for antibiotic prophylaxis and a liquid diet for the first 48 hours. Salivary flow was observed through the Wharton duct on the first postoperative day, and the patient was discharged the same day. Follow-up visits with US assessments at 1 week, 1 month, and 1-year revealed no recurrence of symptoms or formation of new stones.

Discussion

The treatment of sialolithiasis depends on the size, location, and whether it is fixed [3]. Interventional sialendoscopy has been shown to be highly effective for stones between 4 and 7 mm, sialoendoscopy, combined with ESWL, is the preferred treatment. Intraparenchymal and proximal intraductal stones larger than 7 mm may not be removable using sialendoscopic techniques combined with ESWL. These cases often require traditional sialoadenectomy.

Accurate identification of the stone's location is critical in guiding the surgical approach.

When the stone is not palpable, sialoendoscopy illumination, ultrasound (USG), or CT navigation can be used to determine its location. Deep parenchymal stones and distal intraductal stones may be difficult to locate endoscopically due to strictures or kinking of the ducts, preventing the progression of the sialoendoscope [1].

Carroll et al. have proposed using intraoperative US as a guide, but its operator dependence and size of the equipment are disadvantages [4].

For parotid stones, CT has 93% specificity and 94% sensitivity, although dental restorations or radiolucent stones can complicate the diagnosis [5]. CT-assisted navigation can localize radiopaque stones, especially those impacted, with an error margin of ~2 mm, allowing for targeted dissection and stone removal with minimal tissue disruption [6].

Although combined sialoendoscopy with extracorporeal lithotripsy was proposed as the first-choice modality, it was not available in our center, and the patient declined to be referred elsewhere. We did not have sufficient experience with US detection of the stone.

Compared with intraoperative US guidance, CT assistance has higher sensitivity and is easier to interpret than US. However, the CT scan image guidance does not provide real-time images, making it best reserved for fixed immobile stones. Confirmation of the location of the stone with a scope during surgery may be useful. On the other hand, ultrasonography guidance provides real-time images, does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, and is less expensive than CT; however, it is less sensitive and operator-dependent [1].

We acknowledge that slight deviations in navigation accuracy may occur, particularly during prolonged procedures where patient positioning can shift. However, the multi-point verification approach we employed significantly mitigated this issue. By using stable anatomical landmarks, such as the mental foramen and mandibular condyles, and incorporating a forehead marker as a fixed reference point, we were able to identify and correct discrepancies in real time.

This systematic process allowed for precise recalibration of the navigation system when necessary, ensuring accurate localization and successful extraction of the sialolith. These measures minimized the risk of errors and enhanced the overall reliability of the navigation-guided approach.

In our case, after the extraction of the stone, we checked the surgical field with a 2.7 mm pediatric endoscope intraorally, since we did not have a sialoendoscope.

An alternative approach to CT navigation-assisted transfacial surgery exists, but it carries risks of facial nerve injury and skin scarring.

Conclusion

CT navigation-assisted intraoral extraction may offer an alternative to submandibular gland excision, especially for large, fixed, and impacted distal intraductal and parenchymal sialoliths that cannot be reached or have failed treatment with sialoendoscopy. This method preserves gland function, minimizes complications, and avoids cosmetic drawbacks associated with traditional surgical approaches. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of CT navigation-assisted intraoral extraction.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Informed consent

The patient has given his informed consent and consent to the use of his personal information.

Ethical considerations

Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.