-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hidetoshi Shidahara, Masakazu Hashimoto, Keiichi Mori, Shintaro Kuroda, Hiroyuki Tahara, Tsuyoshi Kobayashi, Hideki Ohdan, Curative resection of multiple primary neuroendocrine tumors enabled by preoperative imaging: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 1, January 2025, rjae805, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae805

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Neuroendocrine tumors (NENs) originate from neuroendocrine cells and predominantly occur in the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and pancreas. Although the liver is commonly involved in NEN metastasis, primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumors (PHNETs) are rare. Herein, we report a case of a 52-year-old female who presented with slowly enlarging, cystic, multiple PHNETs. Two tumors in segments 6 (S6) and S7 were noted on computed tomography (CT), and an additional S7/8 tumor was found on magnetic resonance imaging. Additionally, CT during hepatic arteriography (CTHA) revealed a small tumor in S8. No other primary tumors were detected in other organs. Posterior segmentectomy and S8 partial resection were performed for the tumors. The postoperative pathological diagnosis was a grade 2 neuroendocrine tumor. The patient showed no recurrence of tumor 3 years postoperatively. In this study, CTHA was more effective than other examinations in detecting small tumors, which could be resected without any residual tumors.

Introduction

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) originate from neuroendocrine cells and frequently affect the digestive tract, pancreas, and lungs [1, 2]. In the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 18 registry grouping (2000–2012), the highest incidence rates were 1.49 per 100 000 in lung NENs, 3.56 per 100 000 in gastro-entero-pancreatic NENs (GEP-NENs), and 0.84 per 100 000 in NENs with an unknown primary site [1]. Among GEP-NENs, 53%, 20%, and 13% occur in the rectum, pancreas, and stomach, respectively [2]. On pathologically identifying a neuroendocrine tumor within the liver, the initial consideration is often metastasis from other organs. Primary hepatic NENs (PHNENs) are exceedingly rare, representing 0.8% of NENs [3], and typically have a poor prognosis [4]. Here, we describe a case of slowly progressing multiple primary-hepatic neuroendocrine tumors (PHNETs) presenting with cystic lesions.

Case report

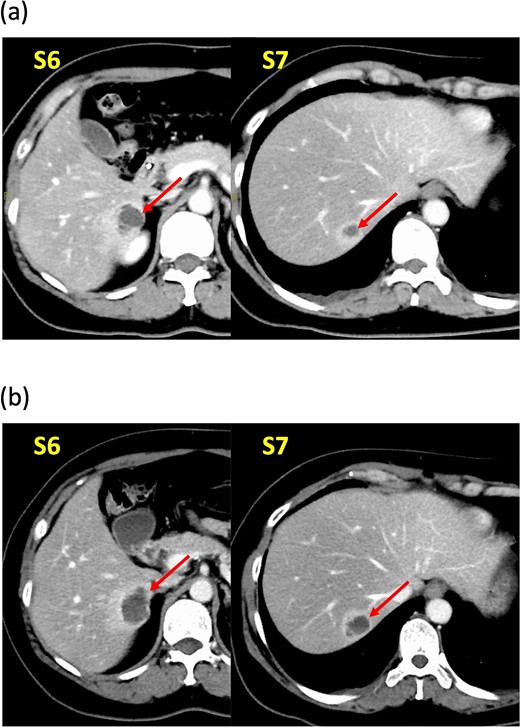

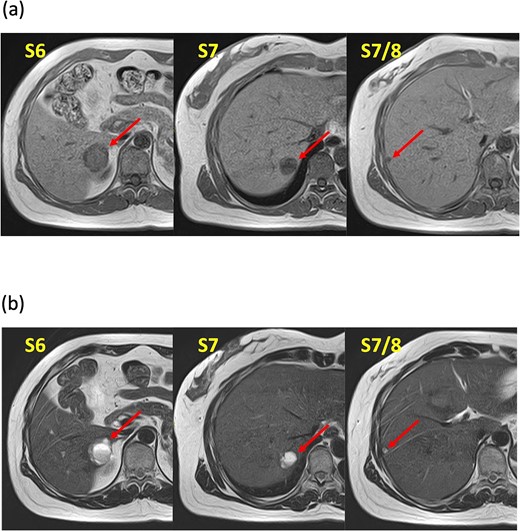

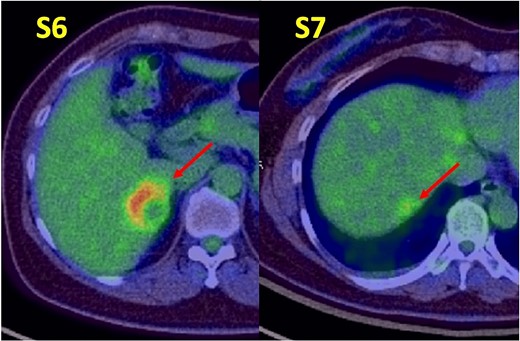

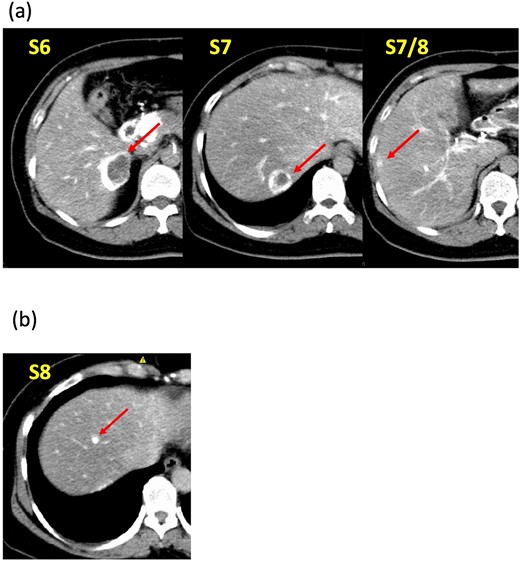

A 52-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital for the evaluation and treatment of multiple cystic liver tumors. Two years earlier, dynamic computed tomography (CT) had detected multiple cystic tumors in segments 6 (S6) and 7 (S7), which were subsequently monitored (Fig. 1a). The patient showed no symptoms; laboratory tests for tumor markers such as α-fetoprotein, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II, carcinoembryonic antigen, and carbohydrate antigen 19–9 were within normal ranges. Dynamic CT identified two low-density tumors with peripheral enhancement in the portal phase, featuring cyst-like internal septa (Fig. 1b), which showed slow enlargement over 2 years. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using gadoxetic acid (gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid; EOB Primovist®) revealed that tumors appeared as low intensity signals on T1-weighted imaging and high intensity signals on T2-weighted imaging and diffusion-weighted imaging. Additionally, a 7-mm lesion was observed at the S7/8 boundary (Fig. 2a and b). Positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) showed abnormal uptake in S6 and S7 tumors but not in the S7/8 lesion (Fig. 3). CT during hepatic arteriography (CTHA) demonstrated well-contrasted tumors at the periphery, with no contrast enhancement in the center (Fig. 4a). Moreover, CTHA detected a new tumor in S8, displaying clear and uniform contrast but not visible with other imaging modalities (Fig. 4b).

Dynamic computed tomography (CT) findings. (a) Two years ago, cystic tumors were detected as low-density lesions surrounded by contrasting tissue in segments 6 (S6) and 7 (S7). (b) Preoperative CT shows both tumors had enlarged slightly.

Magnetic resonance imaging findings. Known tumors are visible in S6, S7, and an additional tumor is found at the S7/8 boundary. These tumors appeared as low-intensity lesions on (a) T1-weighted images and (b) high-intensity lesions on T2-weighted images.

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography findings. Abnormal tracer accumulation are observed in the S6 and S7 tumors.

Computed tomography during hepatic arteriography findings. (a) Known tumors in S6, S7, and S7/8 exhibit peripheral contrast enhancement but lack contrast in their centers. (b) The new tumor in S8 displays a distinct, uniform contrast effect.

Owing to anatomical challenges, a liver biopsy was not performed. CT, MRI, and PET-CT revealed no extrahepatic lesions. Upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopies and small intestinal capsule endoscopy found no abnormalities in the gastrointestinal tract. Given the malignancy potential, the patient underwent posterior segmentectomy, partial resection of S8, and cholecystectomy. The surgery lasted 296 minutes, with an estimated intraoperative blood loss volume of 220 ml. The patient required antibiotic therapy for postoperative pneumonia and was discharged 14 days postoperatively.

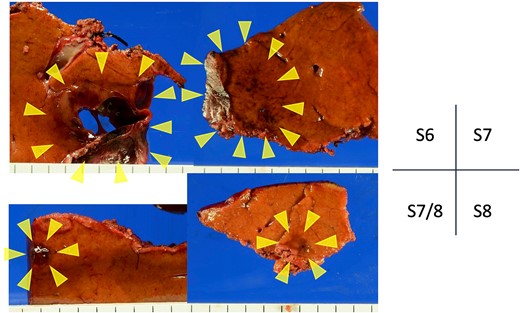

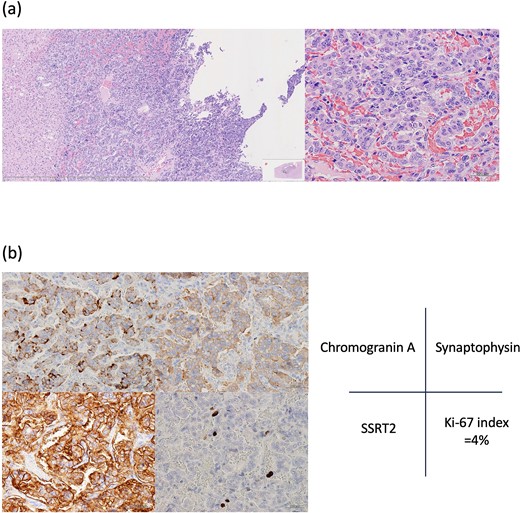

According to the pathology report, all four lesions were fully resected (Fig. 5). Histopathologic examination revealed that the lesions comprised large tumor cells with granular and oval nuclei, organized in cord-like and glandular-luminal-like structures, with no involvement of veins or bile ducts. Cyst-like structures were likely formed owing to tumor-cell spillage, leading to central necrosis (Fig. 6a). Immunohistochemical analyses showed chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and somatostatin receptor type 2 expression. Ki-67 was positive in 4% tumor cells (Fig. 6b). Accordingly, a grade 2 neuroendocrine tumor (NET G2) was diagnosed. As no primary lesions were detected outside the liver, a final diagnosis of PHNET G2 was made. The patient has remained tumor-free for 3 years post-surgery.

Resected gross specimens. All tumors with brownish areas are indicated by yellow arrows. Tumor in S6 with cavities.

Histopathological findings. (a) Hematoxylin–eosin staining shows pleomorphic nuclei and dense chromatin in tumor cells, as well as cyst-like structures likely formed by exfoliated tumor cells. (b) Immunopathological examination: Tumor cells are positive for chromogranin A, synaptophysin, somatostatin receptor type 2 (SSRT2). Ki-67 is positive in 4% of tumor cells.

Discussion

NENs are considered rare, but data from the SEER program indicate a rising incidence in the United States [1]. The World Health Organization’s 2019 classification collectively refers to pancreatic and gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors as NENs, encompassing well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs). NETs are further classified into G1, G2, and G3 based on Ki-67 labeling index values of <3%, 3%–20%, and > 20%, respectively. NECs, characterized by a Ki-67 index >20%, include small-cell and large-cell subtypes [5]. Since the liver is frequently affected by metastatic disease from extrahepatic NENs, ruling out other primary tumor sites is crucial before diagnosing the liver as the tumor origin [6]. In this case, both the Ki67 percentage (4%) and absence of primary lesions outside the liver were pivotal in confirming the PHNET G2 diagnosis.

Investigating NENs in the liver during the preoperative examination requires several diagnostic modalities. Common recommendations include contrast-enhanced CT, MRI, ultrasound, PET-CT, and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, with the modality choice depending on the specific clinical situation. NENs often cause minimal symptoms and are frequently discovered incidentally on CT. Although many NENs are characterized by hypervascularity, those with higher malignancy levels may exhibit reduced vascular density and contrast enhancement, occasionally appearing as cystic lesions [7]. MRI is considered more effective than CT for detecting lesions [8]. The high diagnostic potential of EOB-MRI for liver tumors is recognized and considered an alternative to the invasive CTHA and CT arterial portography [9]. However, the S8 lesion herein was only delineated by CTHA. CTHA appears to enhance the accuracy of hypervascularized tumor detection by imaging immediately after selective hepatic-artery contrast administration. In this case, CTHA showed contrast at tumor margins but none at the center, indicating necrosis. The smaller lesion in S8 had not yet developed central necrosis and displayed only contrast on CTHA. Owing to tumor delineation by preoperative CTHA, we could resect it with no residuals. Furthermore, the patient has been recurrence-free for 3 years post-surgery. Thus, CTHA may be particularly useful for PHNET.

In a study analyzing data from 291 patients, the overall 5-year PHNEN survival rate was 30.2%, while the 5-year survival rate post-hepatic resection was significantly higher at 71.9% [4]. Moreover, two studies reported that patients who underwent hepatic resection for primary hepatic carcinoid tumors achieved 5-year survival rates of 74% and 78%, respectively [10, 11]. These findings underscore hepatic resection as the primary and preferred treatment for PHNENs, highlighting the importance of maximal tumor removal when possible. Prognostic factors for PHNENs include high Ki-67 expression, high tumor grade, and surgical resection [4, 12, 13]. However, alternative treatment options for cases where hepatic resection is not feasible remain limited. Some studies have indicated that transcatheter arterial chemoembolization could be useful due to the rich vascularity of NENs and their predominant arterial supply from the hepatic artery [14, 15]. However, further research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of other treatment modalities, such as radiofrequency ablation, somatostatin analogs, and chemotherapy, in managing these challenging cases.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.