-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rakesh Quinn, Jodie Ellis-Clark, Surgical approach of anorectal mucosal melanoma with locoregional disease – a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 8, August 2024, rjae477, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae477

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Anorectal mucosal melanoma is rare entity. There is currently no consensus on optimal surgical treatment for loco-regional anorectal melanoma that has a favourable outcome. Abdominoperineal resection has not shown a survival benefit over wide local excision due to the inevitable distant recurrence. With local excision considered favourable given reduced surgical morbidity and avoidance of permanent stoma. However, anorectal melanomas are often diagnosed late, with an increased tumour size and depth of primary lesions, increasing the risk of local recurrence and subsequent disease morbidity when excised locally. The decision to proceed to local excision versus abdominoperineal resection is complex, it needs to be individualized, based on primary tumour clinicopathological features and driven by multidisciplinary discussion, with the goal to improve quality and quantity of life. We present a case of a 66-year-old female with anorectal mucosal melanoma with locoregional disease and our surgical approach.

Introduction

Anorectal mucosal melanoma (AMM) is a rare entity, accounting for 1% of all malignant melanomas [1–3]. The disease often presents with rectal bleeding, anal mass, painful defaecation, and/or altered bowel habits [4, 5]. These non-specific symptoms can lead to delayed diagnosis, with 20%–40% of patients having occult distant disease at presentation [6, 7]. Optimal treatment for this rare condition is debatable, with systematic reviews of retrospective studies, case series and case reports providing best available evidence. Local excision (LE) and abdominoperineal resection (APR) are the two available surgical options for management of local disease. However, regardless of surgical management, AMM has a poor prognosis with 5-year overall survival (OS) of 15% [1, 5].

Case

We present a case of a 66-year-old Caucasian female who presented with a few months’ history of perianal pain and bleeding. She is an otherwise fit and healthy patient, with no history of melanoma. Reviewed in the consulting rooms, she was found to have a palpable low rectal mass and was referred for an urgent colonoscopy and examination under anaesthesia. Intra-operative findings found a 3 × 2 cm pigmented friable low rectal mass at the 5 o’clock position, the distal extent at the dentate line. The colonoscopy was otherwise unremarkable, with no evidence of synchronous lesions. We proceeded with per-anal localized excision of the pigmented mass down to muscle and primary closure of the mucosa.

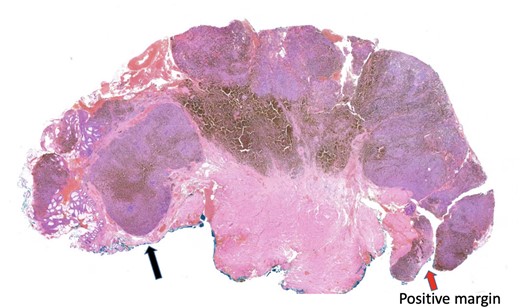

The histopathology report found an ulcerated AMM with positive SOX10, MelanA, and HMB45 immunohistochemistry. The lesion had a mitosis count of 12 per mm2, lymphovascular invasion, no tumour necrosis and BRAF negative. The tumour invaded to a depth of 8 mm into the submucosa, with involved peripheral margins and a deep margin clearance of 1 mm (Fig. 1).

Histopathology slide with involved peripheral margin, labelled ‘Positive margin’.

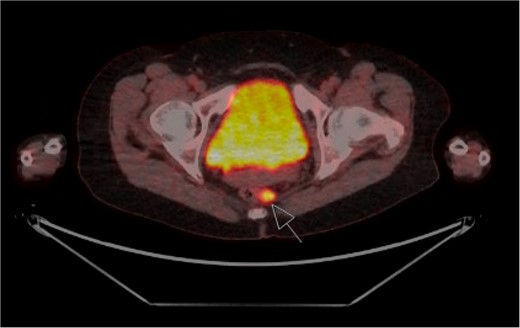

The patient was staged with a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain and fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan which identified several prominent FDG-avid mesorectal lymph nodes concerning for regional disease, with no evidence of distant metastases (Fig. 2). Due to the rarity of the presentation, the case was presented at both colorectal and melanoma multi-disciplinary team meetings. The consensus decision was to proceed to an APR for management of the loco-regional disease. The APR histopathology confirmed Stage 2 disease, with 2/18 lymph nodes involved. There was no residual invasive disease at the site of previous resection, however, a 4 mm submucosal aggregrate of melanophages at the tumour bed was found. The patient recovered well post-operatively and was referred to medical oncology for systemic treatment.

FDG-PET staging scan with enlarged FDG-avid mesorectal lymph nodes (arrow).

Discussion

Unlike cutaneous melanoma, optimal management of AMM is uncertain. In particular standardized treatment for clinically or radiologically node-positive disease without distant metastases is limited to retrospective reviews from epidemiological databases [1, 6, 8]. However these systematic reviews have found that regardless of stage, the two surgical approaches of LE and APR have similar OS, with distant recurrence inevitably occurring [2]. As such, if negative margins can be obtained with preservation of the sphincter function, it has been suggested that LE is preferable.

AMM are often advanced at diagnosis with a median tumour thickness reported between 5-10 mm and median tumour size of 2.2–3.2 cm [8–11]. The feasibility of resection with clear margins and preservation of the internal anal sphincter at this advanced stage needs to be considered. Very few studies document the margin obtained at LE and unlike for cutaneous melanoma there are no evidence-based guidelines to follow. Local recurrence is strongly associated with tumour thickness, and so should be considered for surgical planning [11, 12]. Studies have suggested excision margins similar to the relationship of breslow thickness in cutaneous melanoma [10, 12]. With tumour thickness < 1 mm, a 1 cm margin is sufficient. Tumour thickness 1-4 mm, requires a 2 cm margin with the depth of excision limited by the sphincters. Tumour thickness > 4 mm were associated with high rates of local failure, and LE was insufficient [10, 12]. With several studies reporting that patients who underwent APR had larger tumour size and tumour thickness compared with those who had a LE, suggesting the primary tumour parameters plays a significant role in treatment choice [4, 5, 10].

APR has been shown to have statistically significant improved rates of local control when compared to LE [5, 13, 14]. With studies reporting those with local recurrence often require re-excision, salvage APR or palliative colostomy for symptom and disease control [9, 10]. This potentially compromises the benefits of LE of reduced surgical morbidity and improved quality of life. The addition of adjuvant radiotherapy, in high-risk patients, to sphincter sparing LE has been found to combat this, with reported improved rates of local control of 82% at 5 years [3, 9]. However, radiotherapy is not inert, with a reported late radiotherapy complication rate of 48%, commonly presenting with proctitis and lymphedema [9]. Additionally, despite the promising impact on local recurrence, adjuvant radiotherapy has no impact on disease free survival or OS [3, 9].

Lymph node status in cutaneous melanoma significantly impacts patient’s prognosis and determines adjuvant therapy. Similarly, in AMM, lymph node status provides prognostication, with median survival of 33 months in cN0 and 18 months in cN+ disease [1, 3]. However, studies have failed to show that performing a lymphadenectomy improves OS. A large Chinese database found that the number of lymph nodes involved (1 versus 2–3) in mucosal melanoma significantly impacted OS rates (HR 1.62, 95%CI: 1.16–2.28, P = .001 [15]. Additionally, studies have shown a 26%–34% upstaging in clinically N0 patients, suggesting a high rate of occult regional nodal spread in AMM, implying ongoing value in pathological assessment of nodes for prognostication [1, 3].

There is currently no consensus on optimal surgical treatment for loco-regional AMM that has a favourable outcome. The benefits of LE reducing surgical morbidity and permanent stoma can be outweighed by the local failure rates, feasibility of an R0 resection and complications of adjuvant radiotherapy treatment, with prognostication and local control favouring APR. Ultimately, it is the failure of distant disease control that is the basis of the demise of patients, with further research in systematic treatment needed to address this. Therefore, decision to proceed to local excision versus APR should be individualized, based on primary tumour clinicopathological features and driven by multidisciplinary discussion, with the goal to improve quality and quantity of life.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Funding

None declared.