-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Maryam Hassanesfahani, Jane Tian, Luke Keating, Noman Khan, Martine A Louis, Rajinder Malhotra, Omental infarction following robotic-assisted laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 5, May 2024, rjae343, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae343

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Omental infarction (OI) is a rare condition with an overall incidence of less than 0.3%. It can occur spontaneously or can be secondary to trauma, surgery, and inflammation. While previously a diagnosis of exclusion, due to development in imaging technology, OI can now be identified based on CT findings. OI symptoms can mimic an acute abdomen, prompting potentially unnecessary surgical exploration. Treatment options range from conservative management to interventional radiology or surgical resection of the infarcted omentum. We are presenting the first case of OI following robotic-assisted inguinal hernia repair. This case highlights the importance of considering OI in differential diagnoses for patients presenting with acute abdominal pain, the utility of imaging workup in identifying OI, and guidance for conservative treatment approaches to reduce unnecessary surgical intervention.

Introduction

The omentum is a two-layered folding of the parietal peritoneum hung from the greater curvature of the stomach down to the pelvis with other free edges. It contains fat, lymphatic tissue, and vessels. Omental infarction (OI) is a rare cause of acute abdomen which can occur idiopathically or secondary to trauma, recent surgery, inflammation, hernia, adhesions, or any other possible lead point. Regardless of the etiology, the pathophysiology consists of blood flow interruption leading to venous stasis and edema. OI is a rare condition with an incidence of 0.001%–0.3% [1]. Children and adults with morbid obesity are at increased risk for spontaneous OI due to the heavy burden of fat tissue and omental redundancy.

Although idiopathic OI in children and in non-surgical contexts have been reported many times, relatively few case reports and series have included patients with OI secondary to surgical intervention. Since 1946 when OI was first described, there have been less than 50 cases reported of OI following surgery, but all cases reported on OI were following pancreatic, gastric, or colonic surgery or following cesarean section [2]. The average time for presentation varies from weeks to months after the primary surgery. OI can mimic other possible complications such as pancreatic fistula after the cases of distal pancreatectomy as reported by Javad et al. [3]. It can also be concerning for local tumor recurrence [3, 4] or peritoneal seeding [5].

We are presenting the first reported case of OI following robotic-assisted inguinal hernia repair. This case highlights the importance of considering OI in differential diagnoses for patients presenting with abdominal pain postoperatively, the utility of imaging in identifying OI, and treatment options from conservative to surgical management.

Case presentation

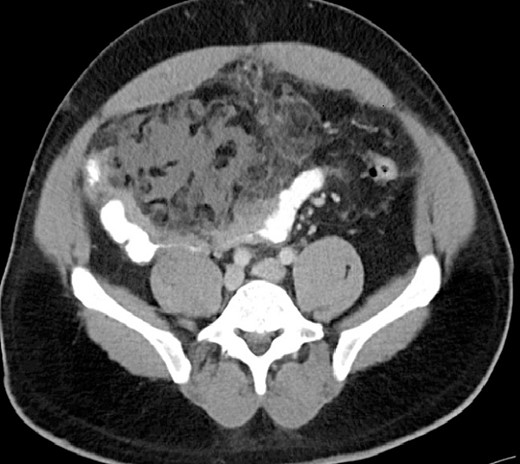

A 44-year-old male underwent an ambulatory, uneventful robotic-assisted laparoscopic left inguinal hernia repair and was discharged to home on the same day. On postoperative Day 16, he came back to emergency room with complaints of 3 days of right lower abdominal pain associated with fever and chills but no other gastrointestinal or urinary symptoms. Other than a temperature of 101.3 F, he was hemodynamically stable. BMI: 33.5 kg/m2. On physical examination, the abdomen was distended, with significant right lower quadrant tenderness, rebound, and localized guarding. The blood work was unremarkable. CT scan revealed localized focal omental edema and inflammation overlying small bowel wall edema and a small amount of free fluid in the lower abdomen (Fig. 1). The patient initially received intravenous hydration and a broad-spectrum antibiotic but failed to improve. He underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy which was converted to laparotomy due to extensive adhesions. Intraoperative findings included a small amount of serosanguineous free fluid in the right paracolic gutter, matted small bowel loops covered with fibrinous tissue, and wrapped within a portion of necrotic omentum. Resection of the omentum and dusky bowel (about 15 cm) with primary anastomosis were done. The patient was discharged in 5 days with no issue. The histopathology review of the omental tissue revealed extensive fat necrosis, focal ossification, and areas of abscess formation, along with focal organizing thrombosis. The resected small bowel had evidence of acute and chronic inflammation with micro-abscess formation involving muscularis propria and serosal surface and surrounding adipose tissue with extensive fibrinous adhesions. No evidence of thermal injury and no micro/macro perforation were seen. The culture of intra-abdominal fluid came back as bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and bacteroides vulgatus anaerobic gram-negative rods.

CT finding of OI with focal omental edema and inflammation overlying small bowel wall edema.

Discussion

In our case, the initial operative finding was a matted bowel with omentum in RLQ with a scant amount of intraperitoneal serous fluid. No free gastrointestinal content and no evidence of hollow viscus perforation were seen. There was no twisting of the omentum; however, it was very edematous at the base next to the transverse colon and completely dusky on the distal side overlying the small bowel. With the initial finding of the matted bowel, the first concern was a possible thermal injury versus a serosal tear with delayed presentation of small bowel perforation. An en-bloc resection of the necrotic omentum, which severely adhered to the bowel, was done. The length of the resected bowel was 15 cm. On postoperative Day 1, the culture of intraperitoneal fluid came back positive with few gram-negative gastrointestinal rods which supported the initial concept of bowel injury. However, the pathology of the resected specimen revealed that there was no evidence of thermal injury with completely healthy mucosa throughout the lumen of the small bowel. There were, however, characteristic findings in favor of OI. At this point, the presence of low-burden gram-negative rods was attributed to sudden impairment of omental function and significant changes in intraperitoneal oncotic pressure that led to bacterial translocation from the small bowel [6]. This highlights that positive culture does not always imply bowel perforation as the initial event.

Clinically, the presentation of OI is often difficult to distinguish from other causes of acute abdominal pain. However, due to developments in imaging technology, CT findings can now identify OI accurately. Although it can mimic intra-abdominal abscess-containing gas with rim enhancement, the presence of heterogeneous fatty attenuation is highly suggestive of OI [7].

OI can be treated conservatively if found incidentally on imaging in an asymptomatic patient as it was done for five patients who were asymptomatic and OI was an incidental finding on their follow-up CT post distal pancreatectomy. However, if the patient is symptomatic, OI should be managed with interventional radiology in case of abscess formation or surgically if there is significant infarcted omentum causing pain or sepsis [3].

Conclusion

OI is a rare condition and was previously a diagnosis of exclusion. However, due to developments in CT technology, CT findings can now be helpful in avoiding unnecessary surgical intervention. OI is a possible complication following upper abdominal surgeries that manipulate the omentum. However, OI can occur even after surgical intervention that does not manipulate the omentum, including, as we report here, inguinal hernia repair surgery. Treatment should be started with conservative management if the patient is stable; in cases of failure to improve or when the diagnosis is in doubt, surgery via laparoscopy or laparotomy is warranted.

Conflict of interest statement:

None declared.

Funding

None declared.