-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Salma Marrakchi, Rania Bouanane, Sara Ez-zaky, Ouiam Taibi, Salma Aouadi, Samia Sassi, Khaoula Lakhdar, Fatima El Hassouni, Nazik Allali, Latifa Chat, Sihame El Haddad, Voluminous cervical polyp delivered: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 5, May 2024, rjae338, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae338

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Cervical polyps are common gynecological findings, typically small and benign. However, larger polyps can mimic malignant neoplasms and pose diagnostic challenges. We present a case of a 40-year-old woman with a large cervical polyp, highlighting the critical role of radiological imaging in diagnosis and management. The lesion was successfully resected, with histological examination confirming a benign nature. This case underscores the necessity for careful evaluation of large cervical polyps to ensure accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Introduction

Cervical polyps are usually small, benign growths of the endocervical canal, commonly encountered in middle-aged women [1]. Although typically asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, they can sometimes present with abnormal vaginal bleeding or discharge [2]. Giant cervical polyps, over 4 cm in size, are a rarity and can be confused with more serious pathology due to their size and presentation [3, 4]. We report a case of a voluminous cervical polyp managed successfully with radiological imaging and surgical intervention.

Case report

A 40-year-old nulliparous woman, presented to the gynecological consultation for abnormal vaginal bleeding. She had no significant medical history. She reported intermittent vaginal bleeding unrelated to her menstrual cycle.

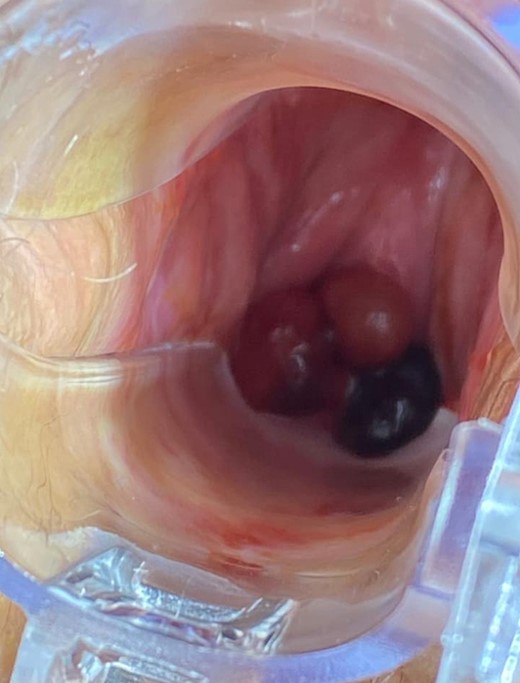

Upon examination with a speculum, a lobulated oval-shaped, red-pink, firm mass occupying a substainal portion of the vaginal cavity was observed (Fig. 1).

Speculum examination revealing a lobulated oval-shaped, firm mass occupying a substantial portion of the vaginal cavity.

Colposcopy confirmed the presence of a voluminous pedunculated mucosal polypoid mass, with poor vascularity, originating from the anterior lip of the cervix.

Pelvic suprapubic ultrasound, did not reveal notable abnormalities, while endovaginal ultrasound, was inconclusive due to interference from the intravaginal polypoid mass.

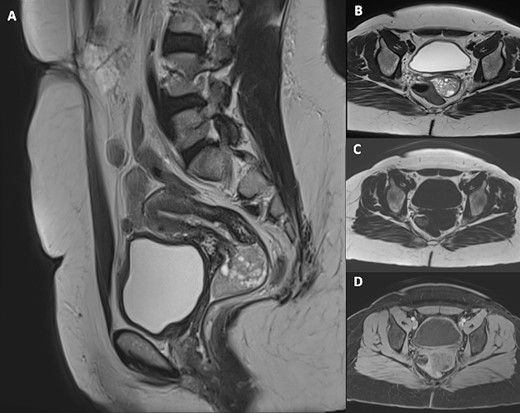

Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a 5 cm × 3 cm × 3 cm intravaginal mass, with endocervical implantation, well-defined, featuring slightly lobulated margins and an oval shape. The mass exhibited the same signal as the endometrium: isointense on T1-weighted images, moderate hypersignal T2 intensity, containing areas of marked hyperintensity on T2. There was no diffusion restriction, and a slight enhancement was observed after Gadolinium injection (Figs 2 and 3). This finding primarily suggested a cervical polyp delivered through the uterine cervix.

Pelvic MRI including sagittal T2-weighted (A), axial T2-weighted (B), axial T1-weighted (C) and axial post-Gadolinium injection (D) images, demonstrating a 5 cm × 3 cm × 3 cm intravaginal mass with endocervical implantation. The mass is well defined, featuring a slightly lobulated oval shape. It exhibits the same signal as the endometrium: isointense on T1-weighted images, moderate hypersignal T2 intensity, containing areas of marked hyperintensity on T2 with slight enhancement after Gadolinium injection.

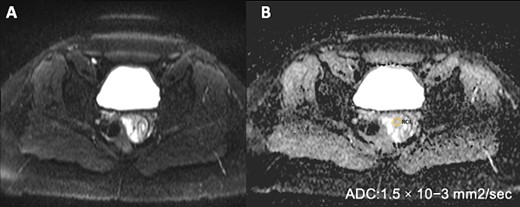

Pelvic MRI on Diffusion sequence and ADC mapping reveals no diffusion restriction, indicated by an elevated ADC value of (1.5 × 10)–3 mm2/s, suggesting benignity.

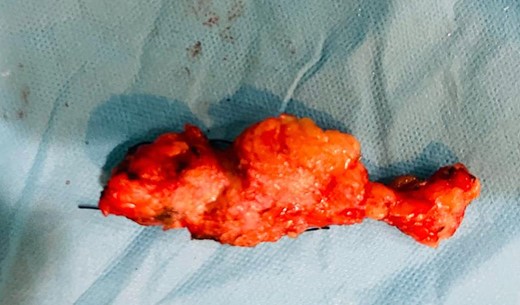

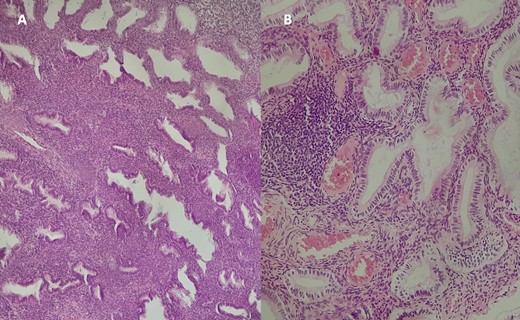

An ultrasonic polypectomy was performed with the Harmonic scalpel under general anaesthesia. The polypectomy specimen (Fig. 4) was sent to the pathology laboratory, where histopathological examination revealed endometrial glands without signs of dysplasia or malignancy (Fig. 5). The patient underwent a postoperative follow-up without experiencing any further vaginal bleeding. The final diagnosis was a voluminous cervical polyp delivered through the uterine cervix, measuring 5 cm, with no signs of malignancy.

Macroscopic view of the polypectomy specimen, measuring 5 cm with a lobulated surface and firm consistency.

Histological examination of the excised specimen with Hematoxylin–Eosin staining at ×10 magnification (A) and ×40 (B) revealing endometrial glands of variable size and shape, often dilated and cystic, lined by a regular pseudostratified cylindrical epithelium. The stroma is cytogenetic with hemorrhagic changes, without signs of dysplasia or malignancy.

Discussion

Cervical polyps are a common gynecological issue, typically without symptoms and often found during unrelated pelvic imaging. When large, they can lead to symptoms like unusual uterine bleeding, pelvic discomfort or fertility problems [5]. These polyps stem from a localized increase in endometrial tissue, varying from single to multiple occurrences, and may attach to the uterus in different ways [5].

While cervical polyps, especially large ones, are seldom cancerous, current studies suggest removing those that are symptomatic or show abnormal cells [6]. Vigilance remains key due to their rare but possible serious progression [7].

A literature review has established that the incidence of endometrial polyps tends to increase with age, particularly among nulliparous and post-menopausal women, although a selection bias is possible due to the higher likelihood of investigating postmenopausal vaginal bleeding [3–5]. Such polyps, especially the large cervical variety, are most frequently observed in adult nulliparous women, aligning with the profile of our case subject [5].

These polyps display a size range from 5 to 17 cm and can be found intravaginally; some may extrude beyond the vaginal introitus spontaneously or during a Valsalva maneuver. They account for 23% of polyps located on the uterus [8].

Commonly reported symptoms of this condition include leukorrhea, malodorous discharge and a range of bleeding irregularities such as abnormal uterine bleeding, menorrhagia, irregular menstruation and postcoital bleeding is often observed in instances where polyps emanate from the cervix [8]. Intermenstrual bleeding and infertility may also occur, as illustrated in our case study. Notably, while pain is not typically described as a primary symptom, patients can be asymptomatic for extensive timeframes [5].

Under microscopic examination, endometrial polyps characteristically consist of a dense fibrous tissue, known as stroma, interspersed with sizable, thick-walled blood vessels and varied glandular structures, all covered by an epithelial surface layer [8, 9].

Diagnostic imaging modalities serve as pivotal tools in the evaluation of uterine fibromas and the detailed examination of the polyp’s base, complementing clinical and colposcopic assessments.

Pelvic ultrasonography is often the initial step, typically depicting a lesion that is hyperechoic with well-defined margins situated within the uterine cavity, demarcating the endometrial walls, and surrounded by a thin hyperechoic halo. Doppler ultrasound can be beneficial, particularly when it successfully delineates the vascular supply to the polyp [5, 10].

Nonetheless, when dealing with cervical polyps, conventional imaging techniques may encounter limitations due to the lesion’s challenging location. In these instances, pelvic MRI is particularly advantageous [5]. The standard MRI protocol include sagittal, oblique axial and oblique coronal views with T1 and T2 weighting, as well as diffusion and contrast sequences. Notably, Diffusion imaging is integral for distinguishing between endometrial cancer, polyps, hyperplasia and normal thickening of the endometrium [11].

Indeed, on MRI, cervical polyps are typically visualized as multicystic lesions on sagittal T2-weighted images, filling the endometrial canal or issuing from the cervix, exhibiting varied signal intensities on T1 and T2 sequences and contrast enhancement [11]. They are isointense relative to the myometrium in diffusion-weighted imaging, a feature confirmed by elevated apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values, aiding in their characterization [12].

The gold standard for histologic assessment of endometrial polyps is hysteroscopic-guided biopsy [12], which enables simultaneous visualization and removal of the lesion. Modern advancements have further refined this technique, allowing for direct visual excision in some cases [12].

Treatment modalities for endometrial polyps range from observational management to various surgical interventions, including polypectomy and, when indicated, hysterectomy. Decisions regarding management are multifactorial, considering symptom burden, the impact on patient daily life, but also the risk of malignancy, fertility implications and the surgeon’s expertise. Clinical outcomes post-intervention is generally positive, with a substantial decrease in symptoms like intermenstrual bleeding noted [5].

In practice, the majority of cases are resolved via polypectomy, though instances necessitating hysterectomy—performed abdominally or vaginally—have been documented. The vaginal approach is particularly advantageous in cases with concurrent conditions such as uterine prolapse, mitigating the need for abdominal surgery [13]. The work of Sheth et al. highlights the importance of a thorough preoperative evaluation to determine the most appropriate surgical route, especially in premenopausal women with large myomatous polyps, where vaginal hysterectomy may be preferable [14].

Despite the benign nature of giant cervical polyps, as documented in several studies, their significant size and omnious clinical presentation can mimic malignant pathology. Therefore, rigorous clinical and paraclinical examinations are imperative to exclude neoplastic disease. Surgical excision remains the primary treatment modality, with histopathological examination providing the definitive diagnosis [15].

Ethic approval

All guidelines have been diligently followed, including those set forth by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), and International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) ensuring transparency in authorship, contributorship and dispute resolution processes.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.