-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Harsimran Panesar, Geoffrey Pelz, Daniel Mansour, Intercostal artery aneurysm presenting as a spontaneous hemothorax in a patient with neurofibromatosis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 3, March 2024, rjad725, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad725

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Beyond the commonly known clinical presentation of neurofibromatosis, vascular pathologies are increasingly becoming a known complication. We present a case of a 41-year-old adult with neurofibromatosis type 1 who came with a right-sided spontaneous hemothorax due to a ruptured 13-mm fusiform aneurysm of the right posterior T9 intercostal artery. Patient underwent a transcatheter angiographic embolization with subsequent video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) for a retained hemothorax. Patient was discharged home on Hospital Day 5, and follow-up imaging demonstrated a complete resolution of the hemothorax. This presented case contributes to literature by demonstrating intra-arterial embolization as a viable option to obtain hemostasis in fragile vessels. However, this may not always result in hemostasis, and VATS should be considered to achieve and ensure complete hemostasis.

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis is an inherited, autosomal dominant pathology leading to germline mutations in either neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), NF2, SMARCB1, or LZTR1, resulting in an unregulated growth of neural crest cells. NF1 is the most inherited subtype, with an incidence of 1:2600–1:3000 individuals. Clinical features include learning impairment, optic and nerve gliomas, café-au-lait spots, axillary and inguinal freckling, and Lisch nodules.

Vascular disease is becoming a recognized complication of NF1 due to decreased elasticity in vessel walls, making them more fragile. The estimated incidence of arterial lesions among NF1 patients is reported as 2.3%–3.6%, which is likely an underestimate [1]. NF1 is diagnosed at a mean age of 11 ± 10 years, with vascular lesions identified around 38 ± 16 years. In a retrospective study of patients with NF1, majority had arterial aneurysms (57.1%), followed by arterial stenosis (28.6%) and arteriovenous malformation (7.1%) [2]. As a result, these patients are at a higher risk of spontaneous hemothorax due to aneurysmal rupture.

Case presentation

The participant has consented to the submission of the case report to the journal.

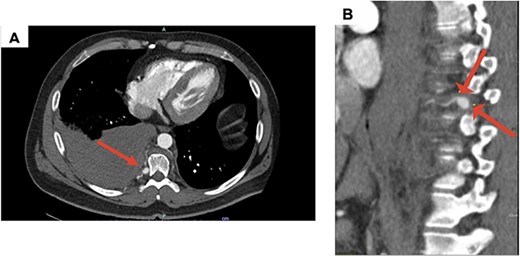

A 41-year-old adult with NF1, presented with a spontaneous right-sided hemothorax after strenuous exercise associated with a presyncopal episode at home. A CT chest angiogram revealed a moderate-to-large right side hemothorax and a 13-mm fusiform aneurysm of the right posterior T9 intercostal artery without active extravasation (Fig. 1A and B). Due to concern for aneurysmal rupture, he was transferred to a tertiary care center.

(A) Axial CT with contrast demonstrating a large right hemothorax on presentation; (B) sagittal CT with contrast, arrows showing T9 intercostal artery aneurysm.

The patient was hemodynamically stable on arrival with a hemoglobin of 11.7 g/dl. He underwent a bedside chest tube placement with immediate evacuation of 1000 cc of blood. Patient remained hemodynamically stable with a total output of 1300 cc over the first 24 hours.

After stabilization, patient was sent to interventional radiology for transcatheter angiographic embolization (TAE) of the T9 intercostal artery. On angiography, the intercostal artery aneurysm was associated with an arteriovenous malformation with venous outflow into the intercostal vein and azygos vein. Therefore, patient has an aneurysm and arteriovenous malformation. The patient underwent a successful coil embolization of the venous outflow, with no filling noted at the completion of the procedure (Fig. 2).

Angiography of T9 intercostal artery aneurysm with successful coil embolization of T9 intercostal artery aneurysm.

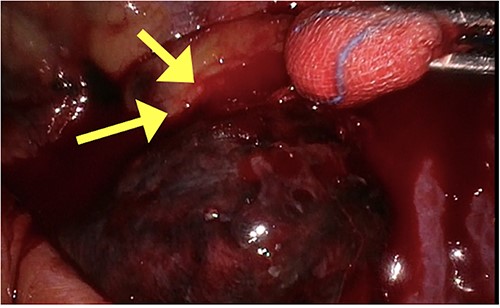

On Hospital Day 2, a repeat non-contrast CT of the chest showed a moderate retained hemothorax. The patient underwent a video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) to remove retained hemothorax. During the procedure, ~300 cc of clots were removed and active bleeding from various small vessels was noted at the location of the aneurysm along with inflamed and friable tissue (Fig. 3). Monopolar and bipolar electrocautery with multiple hemostatic agents were used. Hemostasis was achieved and a chest tube was placed for further monitoring.

Intraoperative picture of aneurysm with friable tissue and bleeding vessel highlighted by arrows.

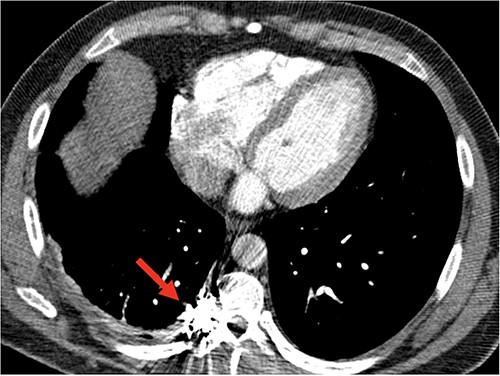

Postoperatively, the chest tube was removed on Day 2, and the patient was discharged to home. The following week, a chest X-ray showed no accumulation of hemothorax. Five weeks following surgery, a repeat CT angiogram demonstrated a stable right T9 intercostal artery embolization coil pack without further evidence of aneurysm or AVM (Fig. 4). The patient was referred to the genetics counseling team for an ongoing follow-up.

Follow-up CT angiogram demonstrated a persistent occlusion of aneurysm, noted by arrow, and resolution of the hemothorax.

Discussion

Individuals with NF1 manifest with a wide spectrum of vascular disorders. The exact pathophysiology of NF1 vasculopathies is not well understood, but the neurofibromin proteins are expressed in the endothelial and smooth muscle layers of blood vessels. When NF1 gene mutation prevents the expression of neurofibromin protein, the vessels undergo an abnormal proliferation, including concentric intimal proliferation with fibrinous thickening, aneurysmal dilatation with irregular smooth muscle loss, and nodular proliferation [1]. Patients with NF1 are at increased risk of bleeding intra- and postoperatively due to vascular dysplasia as well as primary hemostasis disorders related to platelet and collagen interaction.

Spontaneous hemothorax in NF1 patients is a rare but life-threatening complication. Given the fragility of the vasculature, adequate hemostasis is critically important and often technically challenging. Conservative treatment with only hemothorax drainage is not recommended due to a high likelihood of rebleeding. Resuscitative thoracotomy as the initial treatment in neurofibromatosis patients historically resulted in high operative mortality, up to 33%. TAE is an effective way to control bleeding in hemodynamically stable patients and has dramatically improved the outcomes in these patients [3]. Ultimately the patient’s presentation and hemodynamics dictate the initial treatment course. If the patient is stabilized, urgent TAE is the preferred treatment, with surgical intervention reserved for patients with hemodynamic instability. However, in this presentation, a chest tube was placed in the emergency room prior to a thoracic surgery consultation or discussion with the interventional radiologists.

After embolization, the patient had a retained hemothorax, prompting VATS for hematoma evacuation. Despite the embolization, significant ongoing bleeding, given the vascular friability, made it difficult to achieve homeostasis like what is seen in other reports [3, 4]. VATS for retained hemothorax has shown to reduce the risk of infection and length of stay. While the procedure was completed in a minimally invasive fashion, a thoracotomy may be required for adequate exposure and control in difficult cases. Ultimately, this patient had an uncomplicated recovery course and was discharged home without incident.

Clear surveillance guidelines for vascular anomalies in adult patients with NF1 have yet to be described. In a similar reported case, the patient was managed with endovascular embolization, only to present again 7 months later with a spontaneous hemothorax on the contralateral side due to a second ruptured intercostal aneurysm [5]. There are established surveillance guidelines for patients with NF1 regarding neurological, orthopedic, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and psychological complications, but nothing regarding screening for vascular anomalies.

Conclusion

Spontaneous hemothorax in NF patients is a rare but major complication, requiring a prompt diagnosis and intervention. Conservative treatment with the evacuation of the hemothorax alone is not recommended due to high risk of rebleeding and complications. Given the arterial fragility, TAE in stable patients may be the safest way to reach homeostasis. Surgery is reserved for patients presenting with hemodynamic instability or for those with a retained hemothorax following embolization. The case presented here suggests the need for consistent surveillance imaging to monitor for potentially life-threatening vascular malformations, including intercostal artery aneurysms.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this case report.

Patient consent

The participant has consented to the submission of the case report to the journal.

Author contributions

All authors contributed substantially to the conception and design of this manuscript, drafting the work, and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published was given by all authors.