-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Alberto Arcia, Gabriela Alexandra Muñoz, Galo E Jimenez, Monica G Albuja, Thais Suarez Yumbla, Oswaldo H Venegas, Andrea G Velasco, Diana Parrales, Gabriel A Molina, Fishbone perforation of the stomach into the lesser sac and pancreas with abscess, a fishy business, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 12, December 2024, rjae787, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae787

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Ingestion of foreign bodies is common in critical practice. Thankfully, most of these objects will pass without complications; however, sharp and metallic objects can cause severe complications like ulcers and perforation. Perforation of the gastrointestinal tract is rare; however, once it happens, prompt treatment is needed to prevent dreadful complications. We present the case of a 52-year-old patient who presented with abdominal pain and fever. A tomography detected a fishbone perforation of the stomach, which was in the lesser sac attached to the pancreas. After surgery, the patient successfully recovered.

Introduction

Unintentional fishbone ingestion is a common occurrence yet is usually unrecognized until complications appear. Most fishbones will pass without complications through the gastrointestinal tract, but in 1% of cases, it can cause perforation, leading to peritonitis, abscess, and death if left untreated.

We present the case of a 52-year-old male with a fishbone perforation of the stomach; the fishbone caused an abscess in the lesser sac and was found embedded in the pancreas. After surgery, the patient fully recovered.

Case report

The patient is a 52-year-old male with a past medical history of hypertension and kidney stones. He presented with a 5-day history of lower abdominal pain and multiple episodes of diarrhea. At first, the pain was mild and was controlled with painkillers; nonetheless, as time passed, the pain became unbearable; therefore, he presented to the emergency department.

On clinical evaluation, his vital signs were normal; however, severe pain on palpation and tenderness were found throughout his abdomen. Complementary exams revealed leukocytosis with neutrophilia, and due to his pain, appendicitis, cholecystitis, and diverticulitis were among the differential; nonetheless, a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was requested to reach a more definitive diagnosis.

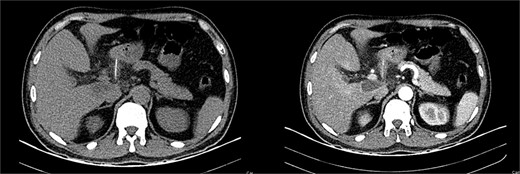

It unveiled a linear hyperdensity behind a thickened stomach wall in the lesser sac, in close contact with the pancreas and duodenum; it had areas of surrounding fat stranding and tissue thickening without pneumoperitoneum. A perforation caused by a fishbone was suspected (Figs 1 and 2).

(A) CT, the fishbone is seen in the lesser sac. (B) Contrast enhanced CT, the fishbone is seen free in the lesser sac in close contact to the pancreas.

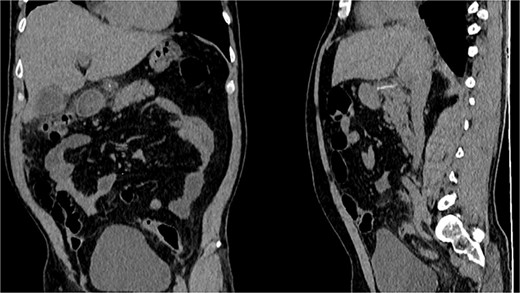

CT, the location of the fishbone in the lesser sac embedded in the pancreas.

With these findings, surgical consultation was required, and surgery was decided. On laparotomy, multiple adhesions were seen between the transverse colon and stomach. After opening the lesser sac, 1000 ml of pus was drained, and after exhausting washing with saline. A foreign body resembling a fishbone was discovered attached to the head of the pancreas and the posterior wall of the stomach and duodenum. No visible perforation was seen in the stomach or duodenum despite numerous maneuvers. With these findings, the foreign body was removed, a culture was obtained, and a drain was placed without complications. (Fig. 3).

Ingested foreign body causing a stomach perforation and abscess was the final diagnosis. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful. He completed a short course of broad-spectrum antibiotics due to the surgical findings, culture results (Sensitive Escherichia coli (E. coli)), and pus drained. Since the drain output was low and serous, it was removed, and he was discharged without complications on the 7th day.

During the outpatient consultation, he recalled eating fish 2 weeks before the pain occurred.

Discussion

Foreign body ingestion is a common condition in clinical practice that usually affects toddlers and patients with psychiatric conditions. [1] Nonetheless, any person can be affected [1, 2]. Thus, >120 million patients per year will suffer from this accidental ingestion, and >1500 will die due to it [2, 3]. Most foreign bodies travel through the gastrointestinal tract (GT) and are passed through the stools without intervention [1, 3].

Nonetheless, 1% of all foreign bodies will cause GT perforation despite the extraordinary capacity of the intestine to protect itself against aggressions [1, 3, 4]. When the intestine is lacerated with a sharp or pointy object, the bowel wall dilates at the point of contact, freeing itself from the object [1, 2]. Yet, all areas of the GT can be exposed to perforation, and it usually happens in places with angulations or that are fixed to the abdominal wall (prior adhesions, surgeries, hernia sacs, diverticulum, appendix) [2]. Among all sharp foreign bodies, fishbone, and chicken bones are the most common cause of perforation due to their sharp tips and long bodies [3, 4]. As it happened to our patient.

Fishbone perforation of the GT can be a challenging diagnosis due to its broad spectrum of presentation, as it will depend on the location and size of the perforation. [1, 5] Symptoms vary from abdominal pain to vomits and fever, and since patients often do not recall ingesting the foreign body, it makes the clinical diagnosis more challenging, and a correct diagnosis is frequently delayed as it can mimic almost every gastrointestinal disorder depending on the site of perforation, including (appendicitis, cholecystitis, diverticulitis, ischemia, among others) [1, 6].

Suppose the perforation is contained in the omentum [1, 6]. In that case, it can mimic an inflammatory mass and, if left untreated, progress to severe peritonitis, which could lead to severe complications and, ultimately, death [1, 2] (Up to 10% mortality rate in missed or delayed diagnosis). In our case, our patient had a 5-day history of diffuse abdominal pain and diarrhea; we suspected that the perforation occurred during this time, leading to his worsening and abscess formation.

There is limited evidence that describes a perforation of the GT into the lesser sac and head of the pancreas; nonetheless, it is believed that when there is a perforation, it is due to the narrowing of the pylorus. When this happens, this perforation is usually delayed [2, 3, 7]. As it happened to our patient who ate fish 2 weeks before this event occurred.

Diagnosis is complicated as many fishbones are not seen in CT due to their intrinsic characteristics [2, 3]. Nonetheless, CT is still the best method to achieve diagnosis [7]. Potential pitfalls of the CT include the presence of contrast, artifacts in the lumen wall, and contrast-opacified small blood vessels that can mimic a fish bone [1, 7].

Extraction of the foreign body without damaging neighboring structures is the treatment of choice; endoscopic approach should be the first option, nonetheless if it fails or is not available, surgical removal via laparoscopic or open approaches can be performed [2, 3]. In our case, the CT revealed the fishbone in the lesser sac, so surgery was decided. After extensive washing, the fishbone was detected and successfully removed.

Even with an exhaustive clinical presentation, the diagnosis will be challenging since the patient’s history may not mention ingesting fish bones or other foreign bodies. Despite the availability of imaging, these rare diagnoses, like foreign bodies that perforate the stomach and are embedded in the lesser sac and pancreas, can still be missed, and many fishbones will be undetected, delaying diagnosis. In these scenarios, clinical manifestations will be critical, and it’s the duty of the medical team not to delay surgical exploration to prevent complications.

Conclusions

Accidental ingestion of fishbones is common, and despite multiple treatments, the best strategy is still prevention. A high index of suspicion and prompt surgery are essential to prevent the potential dangers of accidentally ingesting foreign bodies.

Conflict of interest statement

The author(s) declare(s) that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

None declared.

Ethical approval

All the information from the chart review was given retrospectively, and the patient was de-identified. Waiver of consent was obtained and approved by the Medical Committee of our hospital.