-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Antonio Dekhou, Laurel Bond, Stephanie M Bryant, Dustin A Silverman, Pleomorphic dermal sarcoma of the auricular helix, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 12, December 2024, rjae781, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae781

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Cutaneous malignancies of the head and neck are common; however, superficial sarcomas of the head and neck are relatively rare. We present a 71-year-old unhoused gentleman with challenging access to medical care and poor health literacy who presented with a large, isolated, pedunculated mass of the left auricular helix. Preoperative biopsy was compatible with pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS). The patient subsequently underwent definitive surgical resection with partial auriculectomy and bilateral advancement flap closure. Final pathology confirmed the diagnosis of PDS. Given the rarity of PDS of the ear, we describe a challenging case presentation, diagnosis, and management in an unhoused patient.

Introduction

Cutaneous sarcomatous malignancies of the head and neck are rare. Pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS) is a poorly differentiated mesenchymal tumor that is challenging to distinguish from other sarcomas, specifically atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX). PDS demonstrates invasion of subcutaneous tissue and tends to have aggressive histologic features such as lymphovascular (LVI) or perineural invasion (PNI), necrosis, and increased mitotic activity [1]. While the management of cutaneous carcinomas is clearly described, there is a lack of consensus regarding the optimal management of PDS of the head and neck. We describe a challenging case of auricular PDS in an unhoused patient and its treatment with definitive surgical management.

Case presentation

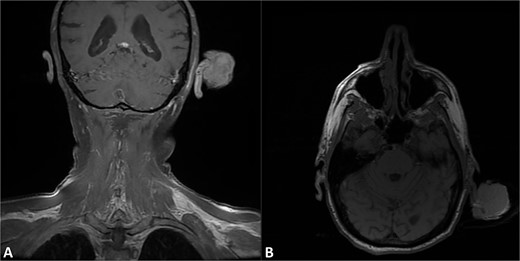

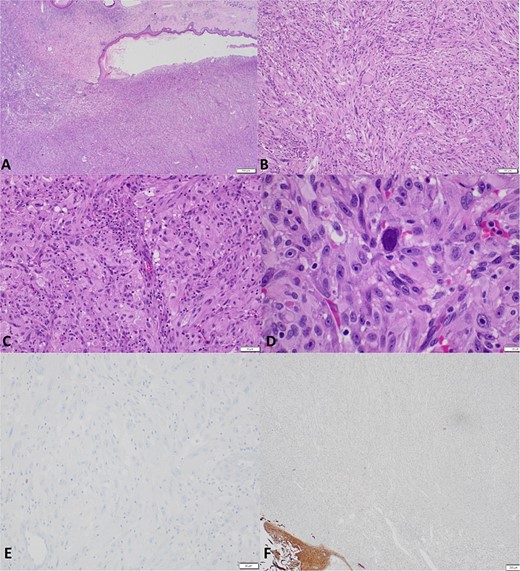

A 71-year-old unhoused gentleman presented to the emergency department for an enlarging 5.5 cm left helical mass (Fig. 1). Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable without cervical lymphadenopathy; House-Brackmann score demonstrated fully functional facial movement and the patient was without audiologic loss. Fat-suppressed, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head demonstrated a 5.5 × 2.2 × 3.6 cm polypoid mass extending from left anterior helix (Fig. 2A and B). A biopsy was compatible with PDS (Fig. 3A–D). Following multidisciplinary tumor board consensus, the patient elected to proceed with definitive surgical management and underwent left partial auriculectomy with bilateral advancement flap closure (Fig. 4A–C). The operating surgeon elected to obtain wider surgical margins to decrease the potential need for adjuvant therapy pending final histopathologic results given the concern for adequate surveillance. Specimen-driven intraoperative frozen pathologic analysis of the auricular skin and cartilage margins were negative for malignancy. Final pathology demonstrated atypical, spindled cells involving the underlying cartilage which stained negatively for keratins (AE1/AE3, CAM5.2), p40, S100, CD21, and CD35. These features, along with additional negative stains performed on the biopsy including p63, SOX10, desmin, and ERG, supported a diagnosis of PDS (Fig. 3E and F). No other adverse tumor features including LVI or PNI were identified; surgical margins were widely negative with the closest tumor margin identified at 1.5 cm. Final pathologic stage was pT3cN0M0 (staged according to AJCC 8th edition for head and neck sarcoma). Given the tumor size, tumor board recommended consideration of adjuvant radiation therapy (RT); however, the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up and failed to present to his 3-week postoperative visit given his challenging socioeconomic status and unhoused status.

Gross representation of left auricular helix mass with a violaceous and fleshy appearance.

T1 fat-suppressed post-contrast MRI of the head in the A) coronal and B) axial sections demonstrating pedunculated mass of the left helix with preservation of the underlying cartilaginous structures.

Representative histologic specimens at A) 20× demonstrating primarily spindle celled tumor with adjacent ulceration into normal tissue, B) 100× demonstrating spindle and epithelial morphology with local inflammation, C) 200× demonstrating nuclear pleomorphism, and D) 600× with significant pleomorphism with relatively low mitotic activity. E) Immunostaining displaying tumor cells negative for S100 (200×). F) A cytokeratin immunostaining highlights the normal squamous epithelium (lower left) but negative in the tumor cells (pankeratin AE1/AE3, 40×).

Intraoperative photos of A) the lesion in situ, B) status post partial auriculectomy, and C) specimen with negative tumor margin.

Discussion

PDS is a rare tumor with overlapping clinical and histologic features with AFX and requires accurate histopathologic analysis [2]. PDS carries a predilection for male sex, scalp and sun-exposed areas, and demonstrates high locoregional recurrence and metastatic disease rates (23%–30% and 10%–20%, respectively) with mortality attributed to progressive metastatic disease [2, 3].

Histologically, PDS tumors lie on the same spectrum as AFX with spindle and epithelial components; however, PDS shows invasion beyond the dermis, and it is more common to have features of LVI or PNI [2]. Importantly, PDS is a diagnosis of exclusion and requires extensive immunohistochemical analysis to rule out other forms of sarcoma, melanoma, and epithelial carcinoma. A panel of immunohistochemical stains to rule out other cell lineages or specific entities is a prerequisite for diagnosis. [4–6] Morphology and immunohistochemistry, including positivity for CD10, are similar in both AFX and PDS, and the differentiating factor between the two pathologies hinges on the presence of aggressive features, common with PDS [6, 7]. In our case, immunohistochemical stains were negative for multiple keratins, p40, and p63 making sarcomatoid carcinoma less likely (Fig. 3E and F). The tumor was also negative for melanoma markers (SOX10, S100) and other sarcoma markers (ERG, desmin, CD21, and CD35).

The mainstay of therapy head and neck PDS involves surgical resection with negative margins, though controversy regarding the role of adjuvant RT remains [8, 9]. Head and neck PDS often borders sensitive cosmetic, functional, and vital neurovascular structures, thus complicating the ability to obtain wider surgical margins. Mohs micrographic surgery may be considered in these cases. Tominaga et al. described the surgical management of recurrent PDS of the temporal bone originally presenting as AFX of the left tragus in an elderly patient treated with total auriculectomy, lateral temporal bone resection, and right anterolateral thigh (ALT) free flap reconstruction with adjuvant RT [10]. Two years following surgery, the patient developed recurrence in the infratemporal fossa requiring re-resection and a contralateral left ALT reconstruction. While the authors’ literature review highlighted a spectrum of pathologic subtypes ranging from AFX to undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, only a single case of PDS was identified involving the preauricular skin or temporal bone; all were treated with primary surgery. The role of more invasive surgical interventions in clinically node-negative patients including sentinel lymph node biopsy or elective neck dissection remains controversial [11].

Given the rarity of PDS, a paucity of evidence supporting the routine use of adjuvant RT exists, though multimodal treatment should be considered, especially in the case of recurrent or advanced stage disease. In a series of 27 patients with PDS most commonly within the head and neck, 18 of 27 patients underwent adjuvant or neoadjuvant radiation while 9 of 27 underwent surgical resection alone [12]. One radiated and one non-radiated patient developed recurrence, though both had inadequate deep surgical margins at first excision. Additionally, the role of chemotherapy remains debated; recent evidence of RAS pathway inhibitors in more aggressive PDS tumors may lend to better outcomes in cases of metastatic disease [11, 13]. Further studies have shown a risk of regional nodal metastasis in up to 10% of cases, and imaging should be strongly considered for appropriate clinical staging and surgical preparation [14]. While imaging did not demonstrate nodal disease, some advocate to perform a concurrent elective neck dissection indicated for more invasive disease or when free flap reconstruction is anticipated. Given the lack of radiographic nodal involvement and isolated helix tumor, a wide surgical margin was safely obtained without additional morbidity. Importantly, given the poor socioeconomic status and lack of housing for our patient, definitive surgical management was pursued during his index admission, similar to prior reported cases in unhoused patients with head and neck malignancies [15].

Conclusion

PDS of the head and neck is rare. Special care to differentiate PDS from other mesenchymal neoplasms including AFX should be taken given its more aggressive and malignant nature. The mainstay of PDS treatment remains surgical resection with negative surgical margins, though adjuvant RT may be considered in select cases. In advanced cases with auricular involvement, elective neck dissection with a wide margin, sentinel lymph node biopsy and selective neck dissection benefit remain debated and may be appropriate in carefully considered cases. It is crucial to take patient specific factors into account when providing surgical treatment for this population.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.