-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jeesoo J Choi, Abigail A Palmares, Sleeve resection of a typical carcinoid tumour in a case of aberrant anatomy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 11, November 2024, rjae756, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae756

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Neuroendocrine tumours of bronchial origin account for ~1%–2%. They can be typical or atypical in nature and are likely to be endobronchial in growth. We report a case of a 37-year-old woman with a carcinoid tumour in the bronchus intermedius with a background of aberrant bronchial anatomy. The tumour was removed by sleeve resection and histopathology confirmed a typical carcinoid tumour. This report describes successful surgical management of this carcinoid tumour despite aberrant bronchial anatomy.

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumours of bronchial origin (carcinoid tumours) account for ~1%–2% of all lung malignancy [1, 2]. They can be typical or atypical in nature and are most likely to be endobronchial in growth [3]. Patients can be asymptomatic or may present with a cough, shortness of breath, or recurrent lower respiratory tract infections with or without lung collapse, due to the endoluminal location of these tumours, and rarely with features of carcinoid syndrome [4, 5]. Surgical resection is the treatment of choice [4, 5]. Aberrant bronchial anatomy is rare and is an important consideration in the planning of sleeve resection and reconstruction of the bronchial anatomy while ensuring bronchial margins are clear [6].

Case report

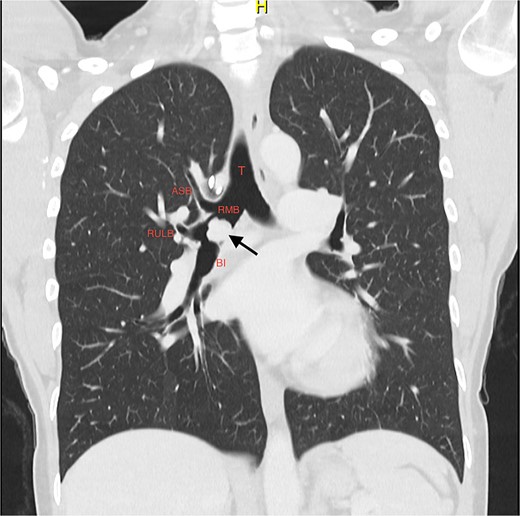

A 37-year-old woman presented with progressive wheeze and shortness of breath. She had been given multiple courses of antibiotics and steroids with only temporary relief. She had been a recent ex-smoker and had no prior medical history. There were no symptoms of carcinoid syndrome. Computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging demonstrated a polypoid mass in the bronchus intermedius, suspicious for a carcinoid tumour (Fig. 1).

Coronal slice of CT thorax pre-bronchoscopy, showing polypoid tumour arising from the bronchus intermedius and the right upper lobe apical segmental bronchus arising from the RMB at the level of the carina; the arrow is pointing to the tumour; T, trachea; RMB, right main bronchus; ASB, apical segmental bronchus; RULB, right upper lobe bronchus; BI, bronchus intermedius.

Her respiratory team were unable to biopsy or debulk the tumour via fibreoptic bronchoscopy, therefore she was referred for endobronchial biopsy and management via rigid bronchoscopy in the first instance.

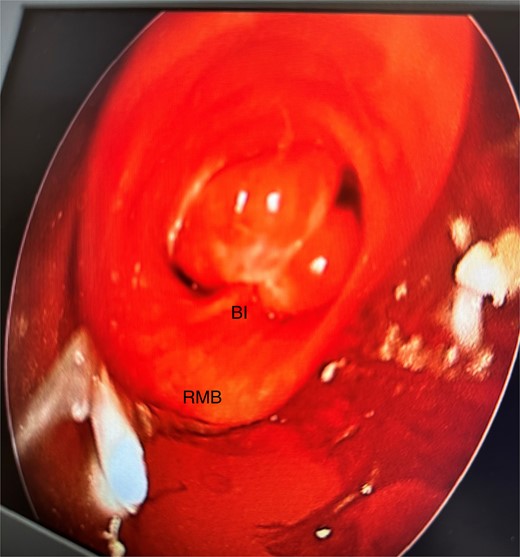

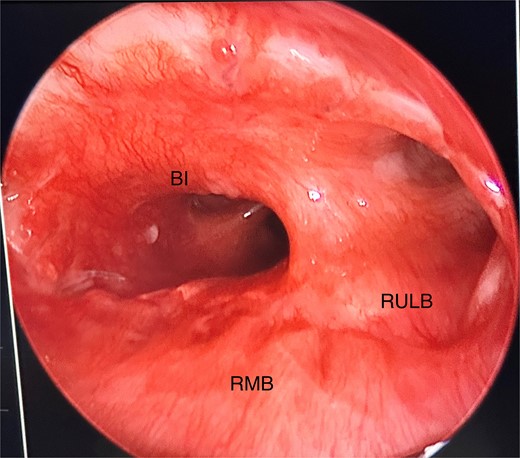

She initially underwent a rigid bronchoscopy, biopsy of the endobronchial tumour, cryoablation, and argon plasma for debulking. On direct visualization with the telescope the tumour was polypoid and was arising from the membranous portion of the right main bronchus (RMB) (Fig. 2).

Initial rigid bronchoscopy showing a polypoid mass originating from the membranous portion of the right main bronchus; BI, bronchus intermedius; RMB, right main bronchus.

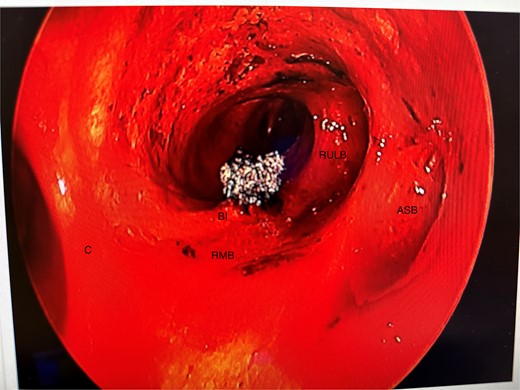

Anomalous right bronchial anatomy was also noted (Fig. 3). The biopsy was sent for frozen section, which confirmed a carcinoid tumour.

Post disobliteration of the tumour through rigid bronchoscopy, also showing aberrant anatomy, where the apical segmental bronchus of the right upper lobe has a high take off at the distal trachea/carina; C, carina; RMB, right main bronchus; BI bronchus intermedius; RULB, right upper lobe bronchus; ASB, apical segmental bronchus.

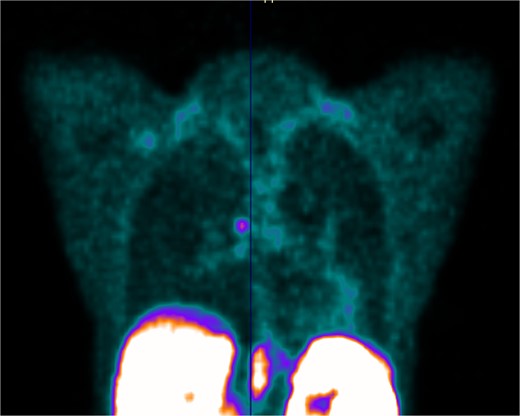

Her case was discussed at our lung cancer multidisciplinary meeting; the biopsy confirmed a carcinoid tumour with no atypical features and the recommendation was for a DOTATATE PET (Fig. 4).

PET scan showing DOTATATE uptake at the level of the right main bronchus; there was no evidence of DOTATATE avid nodal or metastatic disease.

Around 1 month after the initial biopsy and debulking, she underwent a rigid bronchoscopy, right posterolateral thoracotomy and sleeve resection. The rigid bronchoscopy showed no new growth at the tumour bed.

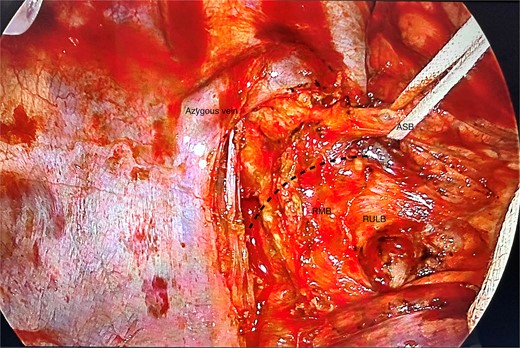

On single lung ventilation the pleural cavity was entered via the fourth intercostal space. An intercostal muscle flap was harvested. The hilar structures were dissected.

The apical segmental pulmonary artery branch of the right upper lobe was ligated with silk ties and divided. Flexible bronchoscopy through the endotracheal tube was performed to find the bed of the tumour and this was marked with a surgical marker on the bronchus on table. The RMB was divided with a knife between the apical segmental bronchus and anterior–posterior segmental bronchus, proximal to the bronchus intermedius (Fig. 5). The apical segmental bronchus was divided from the RMB. A rim of RMB was removed, with the superior and inferior margin marked. This was sent for frozen section analysis—there was evidence of tumour at the superior margin so a further rim of RMB was taken. This was free of tumour.

Posterior view of the right main bronchus and branches dissected; the apical segmental bronchus has been slung; ASB, apical segmental bronchus; RULB, right upper lobe bronchus; BI, bronchus intermedius; dotted line = resection line.

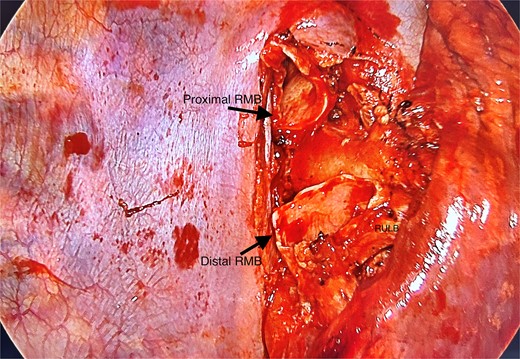

The distal RMB stump with the remaining anterior–posterior segmental bronchus and bronchus intermedius was stitched to the proximal RMB stump with continuous 3–0 PDS posteriorly and interrupted 3–0 PDS anteriorly (Fig. 6). On test ventilation of the right lung, there was good lung reinflation and no evidence of bronchopleural fistula. The apical segment of the upper lobe was completed with multiple staple loads (stapler details). The intercostal muscle flap was divided anteriorly and was wrapped around the anastomosis site and tied in place with a 3–0 PDS suture. Intercostal blocks were administered and a paravertebral catheter was sited for analgesia. Fibreoptic bronchoscopy immediately post-procedure showed the anastomosis was intact.

Posterior view of hilum with tumour resected, leaving behind the proximal and distal right main bronchus stumps; RMB, right main bronchus; RULB, right upper lobe bronchus.

Our patient had a relatively uncomplicated recovery and returned a month later for a check rigid bronchoscopy. The anastomosis site appeared to be healing well with no stenosis from granulation tissue (Fig. 7).

Anastomosis site directly visualized via rigid bronchoscopy, showing good healing and minimal granulation tissue; RMB, right main bronchus; BI, bronchus intermedius; RULB, right upper lobe bronchus.

Discussion

Surgical management is the treatment of choice for endobronchial carcinoid tumours—it allows for complete resection of the tumour and relief from bronchial obstruction [5]. Around 75% of tumours arise in the lobar bronchi, 10% in the main bronchi, and 15% in the lung [5]. Bronchoplastic surgery, preserving distal lung tissue, should be performed if feasible.

Bronchial variations originating from the trachea or main bronchi are rare [6]. The tracheal bronchus encompasses a variety of bronchial anomalies, where the bronchus originates from the trachea or main bronchus. A true tracheal bronchus has been defined as any bronchus arising from the trachea, within 2 cm of the carina, and when the entire right upper lobe bronchus is displaced on the trachea, it is also called a ‘pig bronchus’ [6]. In our case, there were two branches from the RMB to the right upper lobe; the apical segmental bronchus was arising from the RMB at the level of the carina, rather than a single right upper lobe branch as usually observed. In a study of 238 radiological cases, four (1.68%) were found to have variations in right upper lobe branching and one case (0.42%) had the same configuration [7].

Due to the variation in the anatomy, careful surgical planning was required for resection. Carcinoid tumours are slow-growing but can metastasize (4%–20%) to local or regional lymph nodes [5]. It is imperative therefore to ensure disease-free margins. In our case, division of the RMB was performed carefully with the guidance of frozen section in order to confirm disease-free margin while leaving behind enough healthy bronchial stumps to anastomose. The apical segment of the right upper lobe was sacrificed due to the location of the tumour. Mobilization of the bronchial tree reduces tension when anastomosing the proximal and distal stumps. An intercostal flap can be harvested and wrapped around the bronchial anastomosis and is advisable to give structural support and blood supply [8].

The patient has remained well with no respiratory complications on follow-up and multiple check bronchoscopies have shown minimal scarring of the anastomosis.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our multidisciplinary team involved in the care of this patient.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.