-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rossella Prospero, Anastasia Carafa, Paola Francesca Sagrada, Naghia Ahmed, Paola Scagnelli, Michele Maria Ballabio, Giancarlo Garuti, Marco Soligo, Trocar scar abdominal wall adenomyoma following laparoscopic hysterectomy: case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 11, November 2024, rjae650, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae650

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE) within the scar of a trocar insertion is seldom reported as a complication of laparoscopy. We describe the case of a 46 year-old woman suffering from uterine leiomyomas who underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy. One year later, she developed a painful abdominal wall mass, beneath the scar of suprapubic port-site trocar insertion. The diagnostic work-up, consisting in ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging and needle biopsy led to a diagnosis of AWE. Initially, a progestogen therapy was administered, obtaining relief from pain symptoms but insignificant reduction of lump’ size. Therefore, the patient underwent a laparotomic resection of the mass. Pathologic findings showed endometriotic tissue mixed with smooth muscle cells, leading to the diagnosis of extrauterine adenomyoma. Six months after surgery, neither AWE relapse nor incisional hernia was found. To our knowledge, no case of parasitic adenomyoma development in a trocar scar following a laparoscopy has been described before in literature.

Introduction

The first report of a trocar-site endometrioma following laparoscopy dates to 1990 and ~30 cases have been described so far [1, 2]. While abdominal wall endometriosis (AWE) can occur regardless of surgery, it is mostly found after cesarean deliveries [3]. The pathophysiology of AWE within a trocar scar is uncertain. Its etiology is thought to be the inoculation of endometrial cells through the contact of the removed tissues with the port tract [2–4]. Endometrial implantation may also be caused by cell-spreading during the creation of pneumoperitoneum, via aerosolization [4, 5]. However, the wide use of laparoscopy compared with the rarity of this complication suggests that other factors such as immunological, genetic and inflammatory individual pathways might be involved [6]. In most patients, trocar-site AWE is associated with a background of endometriosis while only rarely it was reported in women free from this condition [2]. Among these, the literature describes only two patients who underwent a hysterectomy complicated by AWE [7, 8]. We report the case of a patient developing an abdominal-wall adenomyoma within a trocar-scar after laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Case report

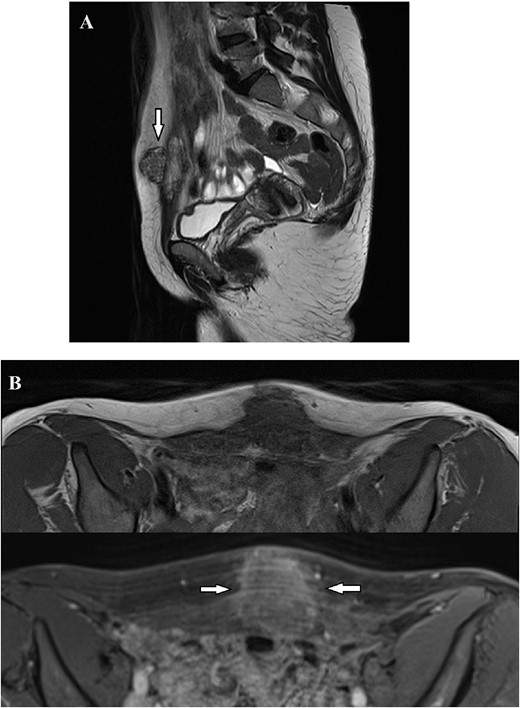

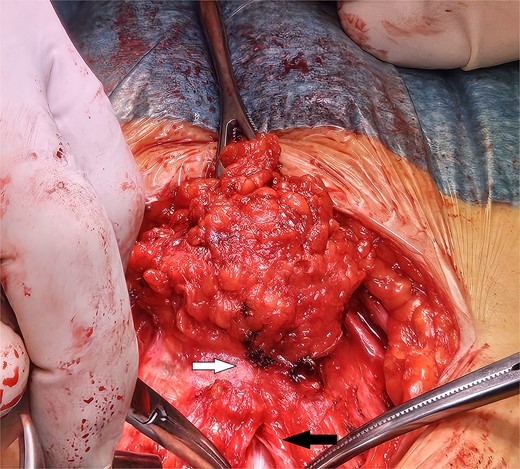

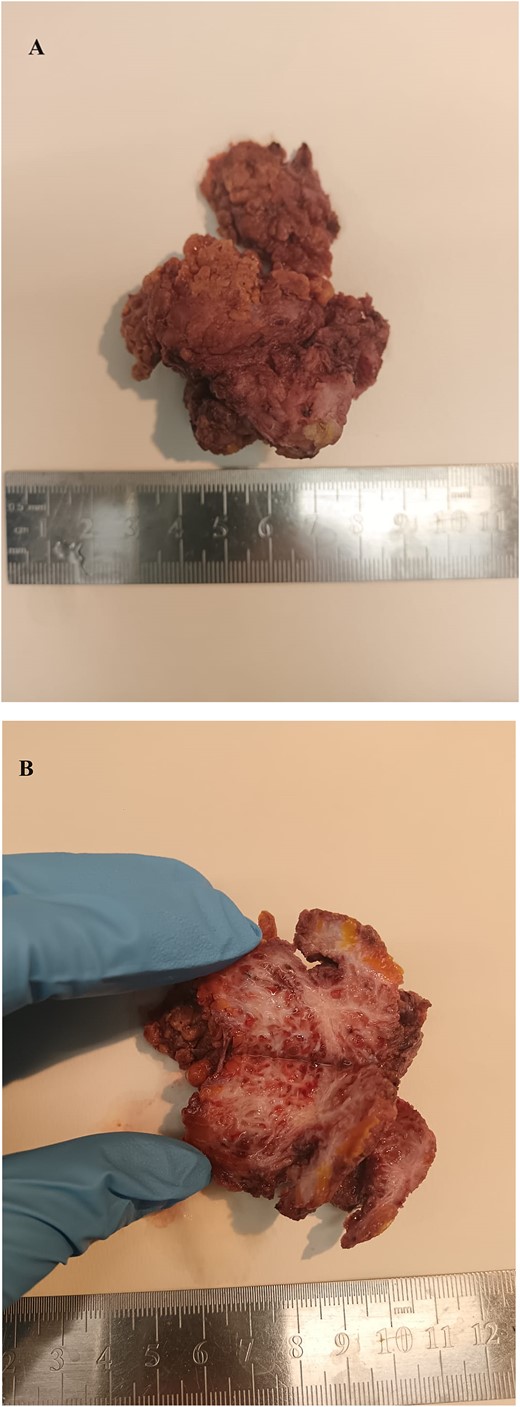

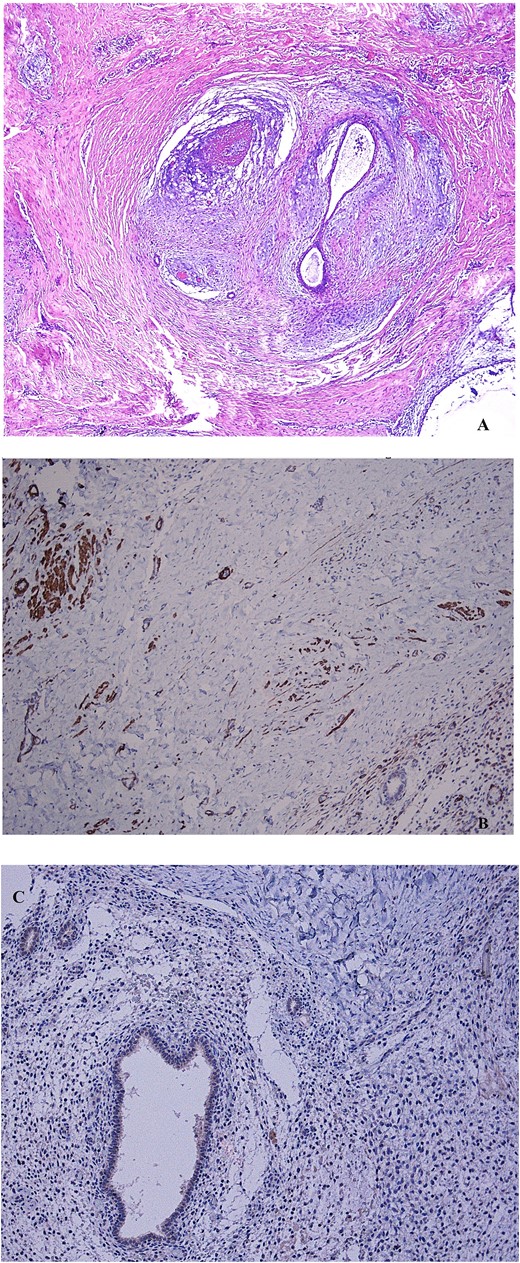

In March, 2022, a 46 year-old woman underwent a laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy for leiomyomas. Her obstetric history included a cesarean birth 10 years ago. The remaining history was unremarkable. Intraoperatively, no sign of endometriosis was found. Supracervical hysterotomy was carried-out with a monopolar knife. Following placement in a sealed bag, the morcellated uterine corpus was exteriorized through the right iliac port. Pathologic examination confirmed common leiomyomas. In April, 2023, the woman presented to her GP complaining of a cyclically painful suprapubic lump. An ultrasonography scan showed a 4 cm inhomogeneous mass with mild vascularization, extended from the rectus muscle to subcutaneous fat. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed a solid irregularly-shaped mass with high contrast enhancement signal (Fig. 1). To rule-out a malignancy the patient underwent oncologic consultation and a through-cut needle biopsy was performed, yielding a diagnosis of endometriosis. The patient came to gynecological consultation in September, 2023. A hard mass, fixed to the underlying abdominal wall layers just beneath the scar of suprapubic trocar insertion was found at physical examination. We planned continuous oral administration of a Progestogen (Dienogest, 2 mg/day). Within the next two months the patient experienced pain symptoms relief but a mass remaining stable in size was found. In February, 2024, the patient underwent laparotomic excision (Fig. 2). Surgical assessment showed an endometriotic infiltration from subcutaneous tissue to fascia transversalis, sparing the peritoneum. The resection was conducted obtaining at least 5 mm margin-free tissue and later, a fascial mobilization from rectus muscles led to a tension-free primary closure (Fig. 3). Progestogen therapy was continued for six months after surgery. The histopathology confirmed an endometriotic tissue with coexistent smooth muscle-cells proliferation, staining positively to Desmin and negatively to Myogenin immunohistochemistry, leading to the diagnosis of extrauterine adenomyoma (Fig. 4). Six months after surgery, no relapsing disease nor incisional hernia were found.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging showed a solid irregularly shaped mass with high contrast enhancement signal, measuring 36×32×26 mm infiltrating the abdominal wall. (A) Nodular formation (arrow) infiltrating the suprapubic area, exhibiting heterogeneous signal in T2-weighted images, extending from the subcutaneous tissue to the transversalis fascia. (B) T1 Weighted images before and after intravenous contrast of Dotarem. Following the contrast infusion, heterogeneous post-contrast enhancement was observed (arrows).

A laparotomy was conducted according to Kustner technique, cutting away from mass boundaries as they were defined through subcutaneous, fascial and rectus muscle dissection. The subcutaneous extension of the mass has been dissected dorsally to the infiltrated fascial layer (upper arrow). In order to safely define the limit of the mass, the median fascial incision and celiotomy conducted above its cranial extension are in progress (lower arrow).

Macroscopic features of the resected abdominal wall adenomyoma. The removed specimen measured ~6 cm and it is shown before (A) and after its equatorial section (B). It appears as a whitish fibrotic mass with irregular boundaries infiltrating adjacent soft tissues.

(A) Non atypical endometrial glands and stroma, surrounded by smooth muscle tissue, representing the mainstay features of adenomyoma, are shown after hematoxylin–eosin stain (4× magnification). (B) The immunohistochemical staining to desmin indicates the muscle cells counterpart of the mass (10× magnification). (C) The negative immunohistochemical staining to myogenin indicates a non-skeletal origin of muscle cells (10× magnification).

Discussion

We described a case in which a hysterectomy performed on a woman without endometriosis was complicated by AWE within a trocar’ scar [7, 8]. The dichotomic histology showing both endometriotic and smooth muscle tissue, qualifying the mass as adenomyoma, has never been documented before in literature. Parasitic leiomyomas within a trocar scar have been reported following laparoscopic myomectomy [9]. Therefore, we consider plausible that concurrent endometrial and smooth muscle uterine tissue seeding and growth within a trocar scar can develop in the same patient. Tissue aerosolization produced by pneumoperitoneum or directs contact of tissues with the abdominal wall injured by trocar insertion are thought to be the main mechanisms for AWE development [6, 10]. Awareness of this complication makes its diagnosis a relatively simple matter. AWE should be suspected in the case of young women with a history of laparoscopy who develops a cyclically painful lump beneath the scar of a trocar insertion. Nevertheless, a differential diagnosis should be considered for abdominal wall metastases, soft tissue sarcoma, incisional hernia, lipoma, or granuloma [2, 3, 11]. Ultrasonography and MRI help to understand the intrinsic characteristics of the mass as well as its relationships with abdominal wall anatomy, whereas needle-biopsy is essential to establish the diagnosis of AWE [12–14]. Progestogen administration is widely used to treat endometriosis and we believed it could be beneficial in avoiding surgery or in shrinking the mass to allow for safer surgical excision. In this case, AWE resulted refractory to our primary therapy. Although this may seem rational, up-front medical therapy is seldom adopted to treat AWE and primary surgical excision is recommended [3, 4, 10]. Following the mass removal, the placement of a mesh can be considered to limit the occurrence of postoperative dehiscence or hernia, depending on the size of fascial defect [3]. The recurrence-rate of AWE has been reported in up to 25% of patients. To reduce the risk of relapse a resection with adequate healthy disease-free margins (5 to 10 mm) is recommended. Furthermore, it is advisable to avoid fragmentation of the mass and to irrigate the surgical field, minimizing local dissemination and diluting parasitic tissue remnants, respectively [3, 6]. Antiestrogenic post-operative therapy, based on progestogens or analogues of gonadotropin releasing hormones may be considered to avoid or delay recurrences [3, 4, 6]. The literature describes two patients undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy complicated by AWE. In both women AWE developed within the suprapubic trocar scar after supracervical hysterectomy [7, 8]. In one patient unprotected uterine morcellation through the suprapubic trocar was described [8] whereas in the other no data has been supplied regarding the mode of tissue retrieval [7]. In our practice, uterine morcellation is accomplished within a sealed endo-bag retriever but despite the cautionary this patient experienced AWE, suggesting tissue-aerosolization within the trocar-site as the mechanism of parasitic implantation. During laparoscopy, advised surgical precautions to limit the occurrence of AWE include firstly the avoidance of tissues contact with the abdominal wall by their protected exteriorization in a retrieval bag. Secondly, a plentiful washing of port sites is recommended to dilute aerosolized parasitic cellularity. Finally, the removal of trocars should follow the deflation of pneumoperitoneum to avoid the “chimney effect” forcing the release of carbon dioxide, reducing the contact between aerosolized tissues and the port sites [4, 5].

Acknowledgements

We thank FA, the patient subject of the report, for signing the consent to publish her sensitive clinical data. This report was conceptualized according to the principles of the 1964 declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. Given the retrospective and observational nature of a case managed by procedures performed as part of routine care, ethical approval was waived by the local Ethics Committee.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

None declared.

References

Author notes

Rossella Prospero and Anastasia Carafa equally contributed as first authors.