-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jhon E Bocanegra-Becerra, José Luis Acha Sánchez, Luis Contreras Montenegro, Microsurgery for brain aneurysms in an accessory A2 and basilar arteries: a rare case presentation and surgical video, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 1, January 2024, rjad742, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad742

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present the case of a 58-year-old male with a 3-day history of sudden onset headache, loss of consciousness, and uncontrolled vomiting. The patient had 3/5 quadriparesis and a Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score of 8, which merited neurocritical intensive care. Brain imaging suggested the presence of two lesions: (i) a fusiform aneurysm of 12 × 7 mm in an accessory A2 artery of the anterior cerebral artery and (ii) an unruptured saccular aneurysm of 3.3 × 2.8 mm in the distal segment of the basilar artery. He was deemed a candidate for microsurgical management. Postoperatively, he had 4/5 quadriparesis, paresis of the right oculomotor nerve, and a GCS score of 13. A 3-month follow-up showed a significant improvement in neurological function with a score of 2 on the modified Rankin scale. The presented case illustrates the relevance of a nuanced acquaintance to operate in diseased anatomical variants and complex pathologies of narrow corridors.

Introduction

The anterior cerebral circulation is supplied primordially by the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) and the middle cerebral artery [1]. Arising from the internal carotid artery (ICA), the ACA is a paired structure that connects each other through the anterior communicating artery (ACoA) and continues independently. However, during embryological development, ACA anatomy variations can occur. An accessory A2 segment is believed to result from (i) the persistence of the embryonic median artery of the corpus callosum or (ii) duplication of one of the ACAs [2–4]. This variant has received several names including medial ACA, the median callosal artery, the median artery of the corpus callosum, the superior callosal artery, third A2 artery, triplicate A2 artery, and accessory ACA. Stemming from the ACoA complex, this vessel can arise as a single or paired structure, thus doting the prefixes of unihemispheric or bihemispheric, respectively [1, 5].

The prevalence of an accessory A2 artery varies between 1% and 13% [1, 2, 6–12]. Prominently, this variant has surgical relevance in the context of aneurysms in the ACoA complex, given the potential supply to the corpus callosum, adjacent cortex, septal nuclei, septum pellucidum, and upper portion of the column of the fornix [1, 2, 5]. For this reason, the rare occurrence of aneurysms with anatomical variants of the ACA–ACoA complex is crucial to knowing and avoiding surgical complications.

On the other hand, aneurysms threatening the posterior cerebral circulation represent defiant entities situated in narrow corridors near vital structures. For instance, basilar aneurysms represent about 5%–8% of all intracranial aneurysms and are associated with high morbidity and mortality [13, 14]. Over the years, they have represented significant challenges for endovascular and microsurgical approaches, bringing great controversy about their management [15, 16].

In this case study, we report the uncommon presentation of a patient with a distal fusiform aneurysm arising from an accessory A2 artery coexisting with a basilar aneurysm. As underscored in the operative video, we describe surgical nuances that accounted for the optimized microsurgical management of both entities via a single craniotomy.

Case presentation

A 58-year-old male was referred to our emergency department with a 3-day history of sudden onset headache, loss of consciousness, and uncontrolled vomiting. His personal medical history was relevant for chronic hypertension. Upon neurological examination, the patient had 3/5 quadriparesis and a Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score of 8, which merited neurocritical intensive care.

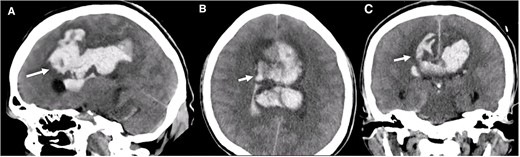

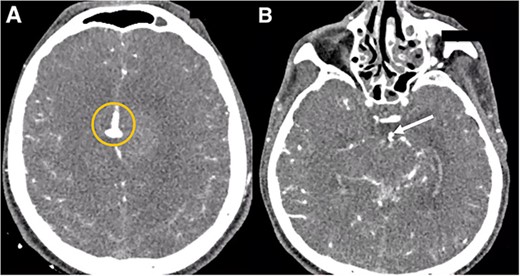

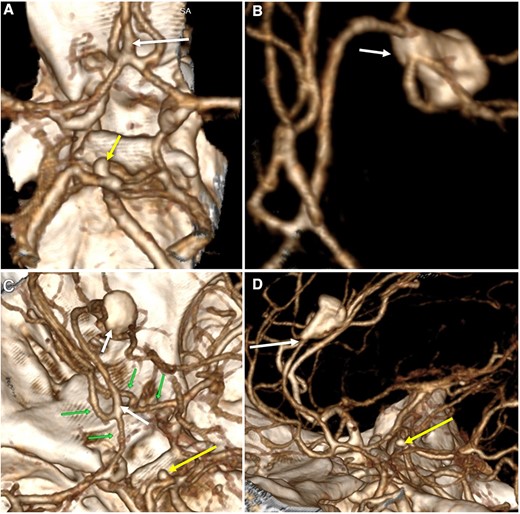

A multislice computed tomography (CT) without contrast revealed an extensive interhemispheric hematoma in the frontoparietal region, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and intraventricular hemorrhage in the adjacent area (Fisher grading score of IV) (Fig. 1). In addition, cerebral angiotomography and 3D reconstruction imaging suggested the presence of two abnormal vascular lesions: (i) a fusiform aneurysm of 12 × 7 mm in an accessory A2 portion of the ACA and (ii) an unruptured saccular aneurysm of 3.3 × 2.8 mm in the distal segment of the basilar artery adjacent to the anterolateral surface of the P1 segment and the left superior cerebellar artery (Figs 2 and 3).

Brain CT without contrast shows a large interhemispheric hematoma, intraventricular hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage (white arrows) in (A) Sagittal, (B) Axial, and (C) Coronal views.

Cerebral angiotomography. (A) Axial cut depicts a midline irregular vascular lesion (yellow circle). (B) Axial cut shows a small saccular aneurysm at the basilar artery (white arrow).

Three-dimensional reconstruction imaging. (A) Superior view of the Circle of Willis shows a variant of the ACA with an accessory A2 branch (white arrow) and a saccular aneurysm of 3.3 × 2.8 mm at the basilar artery (yellow arrow). (B) Inferior–superior view depicts the configuration of the ACA with a triplicated A2 segment and a fusiform aneurysm of 12 × 7 mm emerging in its distal portion, with branches arising from the aneurysm sac (white arrow). (C) Superior view of the anterior and posterior circulation exhibits the complex anatomy of the A1 and A2 segments (green arrows), the accessory A2 segment and distal fusiform aneurysm (white arrows), and the basilar aneurysm (yellow arrow). (D) Lateral view shows the course of the triplicated A2 segment with the fusiform aneurysm arising distally (white arrow) and the small basilar aneurysm (yellow arrow).

After careful appraisal of the patient’s presentation, complex aneurysms’ morphology, and initial medical management in the neurocritical care unit for 14 days, he was deemed a candidate for microsurgical management.

Operative note

The patient was placed supine with a 30-degree head rotation to the left. Next, we performed a right pterional craniotomy with the extension of the opening toward the base of the temporal bone. After carefully dissecting the dura mater, the Sylvian fissure was exposed to access the subarachnoid space, which, in turn, permitted the visualization of the ICA and optic and oculomotor nerves. This dissection maneuver allowed the temporal pole’s mobilization without retracting the neurovascular structures and exposed the interpeduncular fossa (Video 1).

Fine dissection continued until the identification of the A1–M1 bifurcation of the ICA. Then, we visualized the right A1 segment and gained access to the carotid and chiasmatic cisterns. The brain remained relaxed, which allowed for further evaluation of the complex anatomical morphology of the ACA and ACoA. We observed an accessory branch from the ACoA and correlated its relationship visualized in the head CT. Because we had corroborated that the territory irrigated by the accessory A2 artery had collateral supply from both ACA, we safely clipped it proximally, thus excluding the aneurysm from the anterior circulation. Concluding this first stage of surgery, fluorescein angiography verified the permeability of the anterior communicating complex (Video 1).

Subsequently, we assessed the surgical corridors and subarachnoid cistern to clip the basilar aneurysm. Next, following the course of the posterior communicating artery, we localized the basilar artery, the P1 segment of the posterior cerebral artery, and both superior cerebellar arteries. Then, we proceeded to identify and clip the aneurysm neck. Finally, fluorescein angiography confirmed the permeability of the surrounding vascular structures with the exclusion of the aneurysm (Video 1).

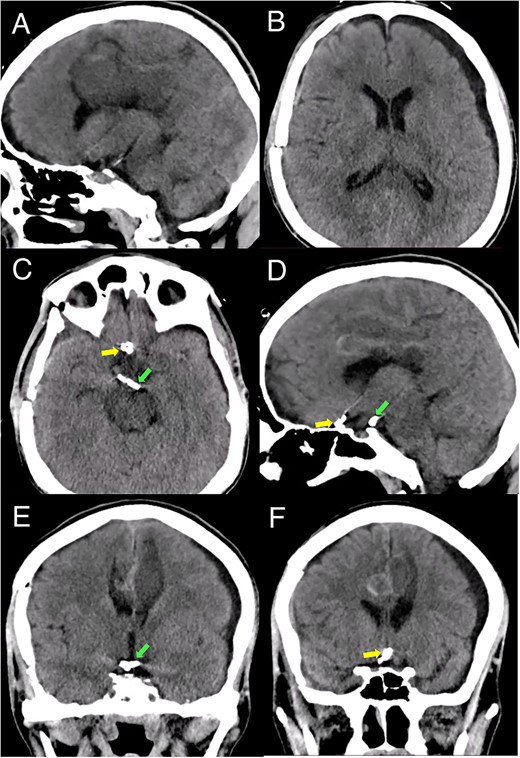

Postoperative course

Brain imaging demonstrated improvement of the hematoma and intraventricular hemorrhage with remnant postinfarction areas (Fig. 4). The patient was transferred to neurointensive care postoperatively, where he remained for 7 days. At this point, the neurological examination indicated he had 4/5 quadriparesis, a right third nerve paresis, and a GCS score of 13. Seven days later, he was discharged with a modified Rankin scale (mRS) score of 4. At the 1-month follow-up, the patient had a GCS of 14 and a mRS of 4. At the 3-month follow-up, the patient showed a significant improvement in the GCS score with a mRS of 2 and improved function of the right third cranial nerve.

Postoperative head CT. (A, B) Sagittal and axial views show resolution of the hematoma and intraventricular hemorrhage with remaining postinfarction areas. (C–F) Postoperative head CT views depict the placement of clips in the accessory A2 artery (yellow arrow) and basilar aneurysm (green arrow).

Discussion

Brain aneurysms are a highly morbid and mortal condition [14]. Treatment strategies have evolved over the years to provide optimal outcomes. However, aside from the patient’s clinical condition, aneurysm’s morphology, and clinical settings, there are particular challenges with approaching these entities, one of which represents the associated anatomical variations of brain vessels [3, 6, 8]. Critically important is the recognition of anatomical variations in the ACA–ACoA complex to avoid ischemic and detrimental clinical outcomes.

The presence of a triplicate A2 artery is not uncommon; however, the presence of aneurysms around this vessel variant is rare [6–12]. Few cases describing aneurysms in the accessory A2 artery have been published, most of them treated surgically and yielding good neurological outcomes [5, 11, 12, 17–30]. Jalali et al. studied 36 patients undergoing aneurysm treatment, of which seven (19.4%) posed the triple-A2 variant. Interestingly, patients with ACoA aneurysms had a significantly higher prevalence of the triple-A2 variant compared with the general population (P < 0.00001) [2]. Moreover, the authors described that patients with ACoA aneurysms that bore the triple-A2 variant were more likely to be treated via open surgery (71%) versus endovascular procedures (29%) [2]. In another study analyzing seven distal accessory ACA aneurysms, Sirin et al. suggested that clipping was the favored treatment modality, and the outcomes were excellent in 86% of cases [5]. On the other hand, it is worth noting that even rarer has been the report of a fusiform subtype of accessory ACA aneurysms, like our illustrated case.

In the presented study, a comprehensive understanding of the anatomic variations around the ACoA–ACA complex could not have been underestimated for achieving a safe approach. As depicted in the surgical video, diligently appraising the anatomical configuration was paramount to properly secure the clipping of the distal fusiform aneurysm in the accessory A2 segment of the ACA. Moreover, the assessment of the surgical corridors and the team’s technical expertise accounted for clipping the basilar aneurysm in a single craniotomy.

Conclusion

Aneurysms of the accessory A2 artery are rare entities that demand nuanced acquaintance with anatomical variations in the anterior circulation. In addition, basilar aneurysms are situated in a narrow corridor near vital perforators and complex anatomy. Both vascular pathologies require dexterity and expertise to provide a safe treatment approach.

The presented case illustrated the uncommon and challenging occurrence of an accessory A2 artery aneurysm coexisting with a basilar aneurysm. Notably, recognizing the anatomy of a vascular variant, its blood supply, and the surgical team’s expertise with pathologies of narrow corridors were of utmost importance in providing safe treatment.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.