-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mohammed Ali Alhamadani, Aleksandr Pecherkin, Terrence Doyle, Primary prostate lymphoma: a rare presentation of lower urinary tract symptoms in young aged patient, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 1, January 2024, rjad598, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad598

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Primary prostatic lymphoma is a rare prostate malignancy that accounts for 0.09% of prostate cancer and 0.1% of lymphoma. Clinical misdiagnosis is common as majority of cases present with non-specific urinary symptoms like other prostatic diseases or prostatic cancer. Early diagnosis is of significant paramount as prognosis is dependent on histological type and tumour staging at the time of diagnosis. Urologists should remain aware of rare histological types of prostate cancer as delayed diagnosis of primary prostate lymphoma can be detrimental and lead to advanced disease causing serious sequelae i.e renal failure in addition to the primary pathology.

Introduction

Lymphoma is a relatively common malignancy which usually originate in the lymph nodes and more rarely in the prostate. Pathologically, lymphomas are divided into Hodgkin’s disease, which is more common, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), which is a heterogeneous malignancy caused by allogeneic B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, or natural killer cells [1]. Prostatic lymphoma can be classified as primary or secondary with the former originates from the prostate. Primary prostatic lymphoma (PPL) is a relatively rare malignant tumour affecting the prostate gland, accounting for 0.09% of prostate neoplasms and only 0.1% of newly diagnosed lymphomas [2]. The majority of cases are NHL, whose main pathological type is diffuse large b-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [1]. Clinical misdiagnosis of prostate lymphoma is common as majority of patients present with non-specific obstructive lower urinary tract symptoms, and early imaging findings are similar to those of prostate cancer [3]. Here in, we report a case of primary prostate lymphoma (DLBCL) in a 25-year-old male who initially presented with undifferentiated lower urinary tract symptoms and progressive worsening of renal function.

Case report

A 25-year-old male presented with six months of lower urinary tract symptoms including frequency, nocturia, poor urinary flow, dysuria, urgency and occasional urge incontinence. Patient’s comorbidities included iron deficiency anaemia, asthma, ankle and mandibular surgery. He was a non-smoker and occasional ETOH drinker. His only regular medication was pantoprazole for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Physical examination was unremarkable. Digital rectal examination showed diffusely enlarged irregular non tender prostate suspicious for malignancy.

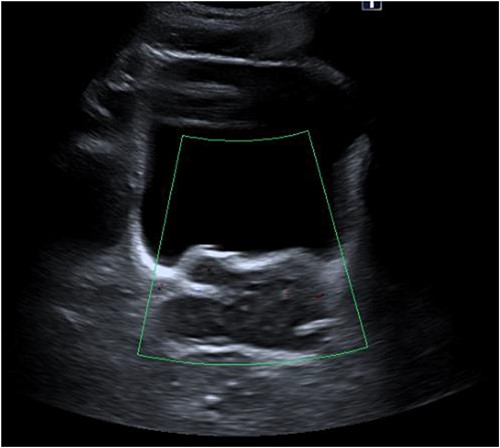

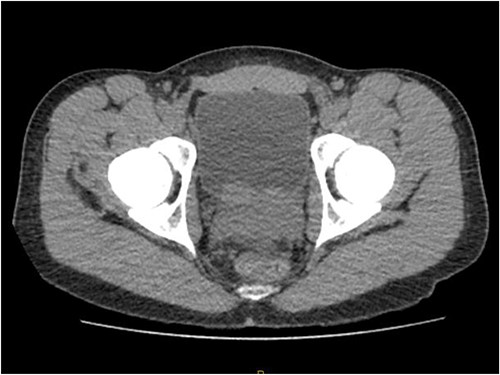

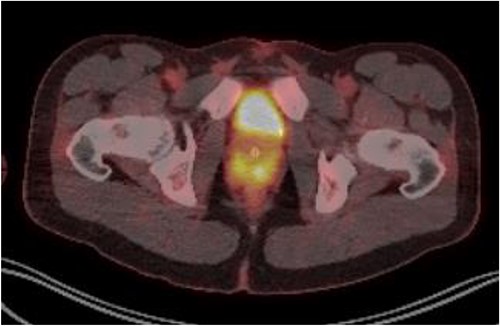

Laboratory tests of full blood count and liver function test were unremarkable with prostate specific antigen of 0.53. Mid-stream urine MCS did not show any infection and urine cytology was negative. Renal function test revealed progressive worsening of previously normal eGFR down to 27 ml/min. Initial renal tract ultrasound (Fig. 1) showed enlarged prostate indenting into the bladder base with high post micturition urine residual volume of 185 ml but no hydronephrosis. CT KUB (Fig. 2) showed irregularly enlarged prostate with bilateral hydroureteronephrosis. MRI prostate showed enlarged prostate with PIRADS 5 amorphous mass suspicious for carcinoma involving bilateral seminal vesicles and right vesicouretric bladder. FDG PET (Fig. 3) showed unusual distribution pattern of lymphoma involving the prostate with bilateral symmetrical renal, early pulmonary, and possibly right thyroid lobe involvement.

Renal ultrasound showing enlarged prostate indenting into the bladder.

PET FDG scan pre-R-CHOP chemotherapy showing disease activity in the prostate.

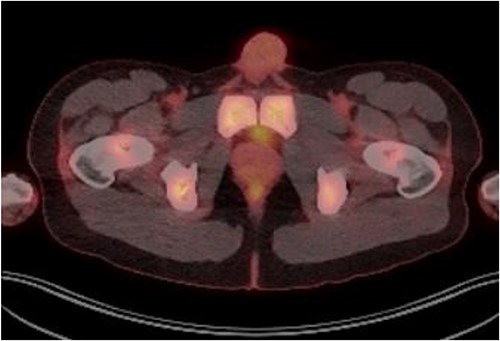

Patient was catheterised and subsequently underwent bilateral ureteric stenting. Cystoscopic views of the prostate was also abnormal and concerning for malignancy, so transperinal prostate biopsy was performed. Histology of this confirmed diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Renal function improved post ureteric stenting and patient was referred to haematology for management of DLBCL. Progress FDG PET scan (Fig. 4) 3 months post R-CHOP chemotherapy showed complete metabolic response with no avid residual lymphoma.

PET FDG scan post R-CHOP chemotherapy showing prostate with complete resolution from the disease.

Discussion

Prostate lymphoma is classified as primary or secondary according to tumour’s origin with the former originates from prostate [4]. Primary prostate lymphoma is defined using the following criteria: [1] The tumour is confined to the prostate and surrounding soft tissues; [2] there is no lymph node involvement; and [3] no systemic lymphoma is detected at least 1 month after the diagnosis of the primary tumour [5].

Primary prostate lymphoma (PPL) is relatively a rare malignant tumour affecting the prostate gland, accounting for 0.09% of prostate neoplasms and only 0.1% of newly diagnosed lymphomas [2]. PPL is more common in elderly people, with mean age of incidence is 62 years, while secondary prostate lymphoma occurs in relatively younger people [6].

Various subtypes of NHL of the prostate have been reported, including but not limited to follicular lymphomas, Burkitt lymphomas, mantle cell lymphomas, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas; however, Diffuse large B cell lymphoma remains the most common [7].

Patients with PPL present with non-specific urinary symptoms similar those of other prostatic diseases and hence clinical misdiagnosis is common [8]. Majority of patients present with nonspecific obstructive urinary symptoms such as frequency, nocturia, dysuria, hesitancy, urgency and occasionally as haematuria or acute urinary retention. Specific lymphoma B-symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and weight loss rarely appear in the early stages [3, 5].

The final diagnosis is usually delayed due to the non-specific clinical symptoms at presentation and achieved by pathological and immunohistochemical examinations of samples obtained by transperineal prostate biopsy or transurethral resection of prostate [5]. Cystoscopy, renal and abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography scan, bone scan, bone marrow aspiration, PSA, and LDH are used for accurate staging and to assess the prognosis of the disease. PSA level is usually at lower normal range comparted to prostate cancer elevated PSA [9].

Due to the paucity of reported cases, there is no established consensus for the management. Reported treatment in literatures include radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy or combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy [3]. R-CHOP chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy is the treatment of choice. Surgical intervention with radical prostatectomy or TURP does not improve survival rate but it can be of diagnostic value if needle biopsy is equivocal [9]. Most cases reported in recent years were treated with R-CHOP regimen, and in patients with B-cell lymphoma, the addition of rituximab can improve outcomes [2, 3]. Radiotherapy is rarely given alone, but it can quickly relieve symptoms of acute urinary tract obstruction and reduces the rate of local recurrence [3].

The prognosis of prostate lymphoma is poor and is dependent on tumour stage, histologic type, and therapeutic modality. Bostwick and Mann [5] case series of 62 patients with primary prostate lymphoma reported a 1-, 2-, 5-year survival rate of 64%, 50%, and 33% respectively. Tong Fang case series of 29 patients with PPL reported a median overall survival rate of 23 months.

This article reported an extremely rare case of primary prostate lymphoma with unusual presentation of lower urinary tract symptoms and acute renal impairment in a young aged patient. Clinicians and urologists need to keep high index of suspicion for prostate lymphoma when assessing patient with urinary symptoms as early diagnosis is of significant paramount and improve prognostic outcome. More studies will need to be conducted to further evaluate PPL in young aged population [10].

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding

For the publication of this case report, no funding was received from public or private health sectors.

Data availability

No data were used to write this case report.