-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kirby Laslett, Jonathan Reddipogu, Taste of variety as a rural general surgeon: granular cell tumour of the tongue, a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 9, September 2023, rjad539, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad539

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Granular cell tumour (GCT) is a relatively rare, benign tumour. The cells of a GCT are composed of large polygonal cells containing numerous eosinophilic granules in the cytoplasm and are thought to be of neural origin. GCT can occur anywhere on the body, but most commonly it is located on the tongue. GCT possess the potential for malignant transformation, and as such should be resected; the risk of malignant transformation is estimated to be 1%–2%. Patients generally do not require routine follow-up following excision with clear margins. Here, we present a case of a GCT of the tongue which had been present for 4 years in an otherwise healthy 35-year-old male. The lesion had been stable in size and appearance, and the patient was asymptomatic. An incision biopsy of the lesion revealed findings consistent with a GCT, and the patient underwent a wide local excision shortly after incision biopsy.

Introduction

Granular cell tumour (GCT) is a relatively rare, benign hamartomatous tumour [1]. The cells of a GCT are composed of large polygonal cells containing numerous eosinophilic granules in the cytoplasm [2]. Under electron microscopy, GCT cells resemble Schwann cells and stain positive for S100 protein, hence it is thought they are of neural origin [2]. GCT can occur at virtually any site of the body, but most commonly it is located intra-orally, and here it is most often located on the tongue or buccal mucosa [1]. These tumours have a female to male predominance of 2:1, and typically present between the ages of 30 and 60 years old [2]. Here, we present a case of a GCT of the tongue, which had been present for 4 years in an otherwise healthy 35-year-old male.

Case report

A 35-year-old male presented to the outpatient clinic of a rural general surgical department, complaining of a tongue lesion for 4 years. The patient had recently showed this lesion to his GP during a routine visit, and from this he was referred to the surgical clinic. The lesion had otherwise been stable in size and appearance; the patient denied pain, discharge, bleeding, difficulty chewing, or dysphagia. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms or unintentional loss of weight.

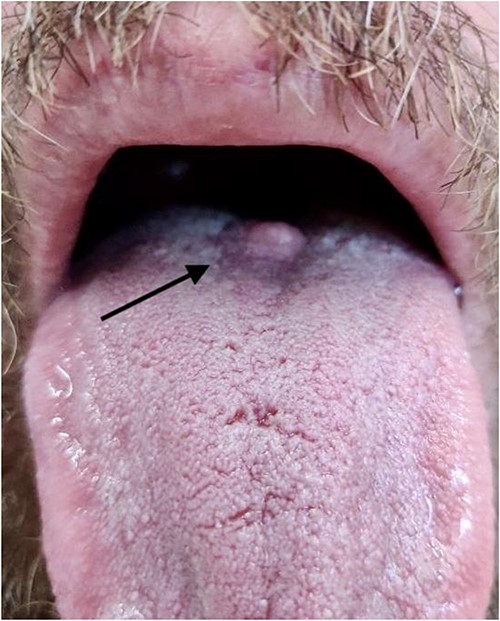

The patient’s past medical history consisted only of hypertension for which he took valsartan. He was an active smoker, 20 cigarettes per day for 20 years, and occasionally drank alcohol. His family history consisted of an uncle with pancreatic cancer, and father with lymphoma. On examination, the patient appeared well with normal vital signs. There was a nodular lesion measuring ~8 × 8mm, located at the junction of the anterior two-thirds and posterior one-third of the tongue, on the dorsal surface. The lesion was well-circumscribed, firm, and whitish in appearance (Fig. 1). There was no palpable lymphadenopathy in the neck.

Photograph of lesion pre-operatively, arrow indicates position of lesion at the junction of the anterior two-thirds and posterior one-third of the dorsum of the tongue.

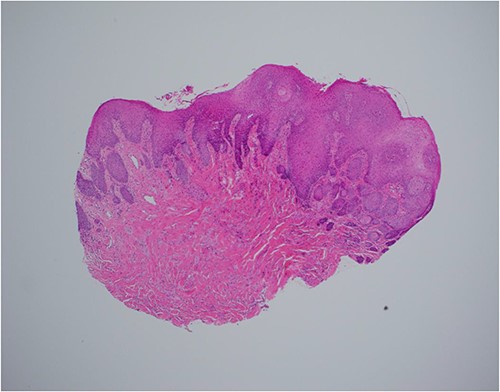

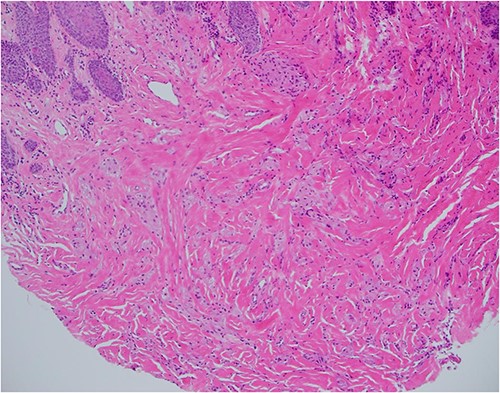

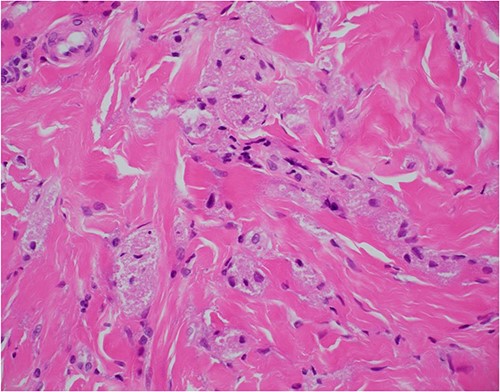

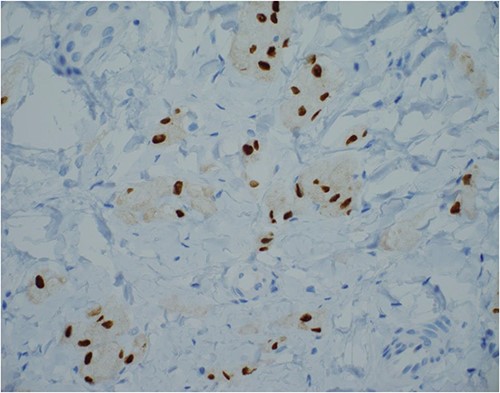

Neck ultrasonography revealed no lymphadenopathy, and normal appearance of the thyroid gland. An incision biopsy of the lesion revealed findings consistent with a GCT (Figs 2–4), and stained positive for SOX-10 protein (Fig. 5). Subsequently, magnetic resonance imaging of the head and neck was unable to identify the lesion following biopsy, and showed no concerning lymphadenopathy or regional dissemination. The lesion was also not visible on computed tomography imaging of the neck.

Haematoxylin and eosin stain, 40× magnification, showing reactive epithelial hyperplasia on the surface, this can be mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma in a superficial biopsy.

Haematoxylin and eosin stain, 100× magnification, showing tumour cells in stroma that may not be sampled by a superficial biopsy.

Haematoxylin and eosin stain, 400× magnification, showing tumour cell features of nests of epithelioid cells in the stroma with indistinct borders and granular pale eosinophilic cytoplasm.

SOX-10 immunostain, 400× magnification—an alternative to S100 immunostain.

The patient underwent an elective wide local excision of the lesion shortly afterward. The surgery was uncomplicated; the remnant scar at the site of the lesion that was biopsied was removed with an elliptical incision including a 5 mm margin. The patient was well post-operatively and discharged home the following day.

At outpatient clinic review 2 weeks post-surgery, the patient had recovered well. The wound had healed, and he was tolerating diet, with no pain or dysphagia. The histopathology of the excised lesion demonstrated scarring only, residual tumour was not seen.

Discussion

GCT is a rare, benign tumour thought most likely to be of neural origin. It was first described by Weber in 1854, then in more detail by Abrikosoff in 1926, and originally thought to be of a myogenic origin, and hence gave it the name granular cell myoblastoma [3]. Since it was initially described, the likely origin is now thought to be neural and not muscular, and so the term GCT is used [1, 3].

GCT can be found anywhere in the body; however, most commonly it is found in the tongue, skin, nervous system, respiratory tract, breast, urinary bladder, and gastrointestinal tract [1]. The majority of lesions are found in the head and neck region, and of these ~70% are found intra-orally [1]. The incidence of this tumour is not well documented, reported as ~1:1 000 000 population per year in one study [2]. There are no known geographical or racial differences in incidence; there is, however, a clear female to male predominance of ~2:1 [2].

The typical appearance of a GCT is that of a solitary, firm, nodular lesion, that is, usually asymptomatic [1]. The lesion is commonly found in the subcutaneous or submucosal layers, generally with an intact overlying epithelium [1]. GCT lesions typically measure < 3 cm in diameter are of hard or firm consistency, with a pink or sometimes whitish/yellow surface colouring [1, 2]. In some instances, larger lesions may also possess an area of surface ulceration [1].

Histologically, GCT typically contain polygonal cells that show numerous cytoplasmic granules [1, 2]. On immunohistochemistry, the cytoplasm stains positive for S100 protein [2]. Nuclear and cellular pleomorphism is absent, and mitotic activity is rarely observed [2]. The overlying epithelium of a GCT has on occasion been noted to possess pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, which can sometimes be misinterpreted as squamous cell carcinoma if the biopsy size is too small, which can lead to misdiagnosis of a GCT [2].

Although a rare occurrence, GCT possess the potential for malignant transformation, and as such should be resected. The risk of malignant transformation is estimated to be ~1%–2% [2]. Features concerning for a malignant GCT include the size of the tumour, rapid growth, pain, and of course invasion of adjacent tissues and/or the presence of metastasis [1]. Malignant GCT can be differentiated from atypical GCT according to the histological criteria proposed by Fanberg-Smith et al. [4]. The type of resection of a GCT depends largely on the location of the GCT, a wide local resection is most appropriate for lesions found intra-orally [1]. Endoscopic mucosal resection would be most appropriate for lesions found in other locations such as the oesophagus, for example [5]. Recurrence following resection with adequate margins is uncommon [2]. In those lesions that do recur, radiotherapy can be considered, and there is no established role for chemotherapy [2]. Routine follow-up following excision with clear margins is generally not recommended [2].

GCT of the tongue is a relatively rare benign tumour of likely neural origin, and although it is benign and the risk of recurrence is relatively low, there is a potential for malignant transformation [2]. This case report adds to the literature and combined understanding of this rare tumour, and highlights the variety of cases that are encountered as a rural general surgeon.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr Sean Chang, pathologist at SA Pathology, based at the Royal Adelaide Hospital, Central Adelaide Local Health Network, for his assistance in obtaining the histopathology photos and reports.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient prior to writing this case report.

Funding

None.