-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Timothy McAleese, Aathir Ahmed, Mark Berney, Ruth O’Riordan, May Cleary, Kocuria rhizophila prosthetic hip joint infection, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 8, August 2023, rjad484, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad484

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present the first case report of prosthetic joint infection (PJI) caused by Kocuria rhizophila. Our patient is a 74-year-old male who underwent primary total hip replacement for right hip pain. His recovery was uneventful until 6 weeks postoperatively when he presented to his routine outpatient appointment with significant erythema, swelling, and tenderness over his right hip wound. Based on the acuity of his symptoms and the radiological findings, it was determined that the patient should undergo debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention (DAIR procedure). A consensus decision was also made at our PJI multidisciplinary meeting to treat him with 12 weeks of IV antibiotics. After completing this 12 weeks course of IV Vancomycin, his inflammatory markers returned to normal limits. At 6 months follow-up, our patient was mobilizing independently without any signs of infection recurrence. His radiographs showed the implant was in a satisfactory position with no evidence of loosening. This case adds to an emerging body of literature describing invasive infections associated with Kocuria species. We have demonstrated the effectiveness of managing this condition with debridement, implant retention, and IV Vancomycin therapy for 12 weeks.

INTRODUCTION

Kocuria species, a member of the Micrococcaceae family, was previously considered a harmless commensal bacterium of the skin and oral cavity. However, with the recent improvement in identification technology, there has been a rise in reported cases of Kocuria species causing significant infection, particularly device-related infections. It is also now known that infections caused by Kocuria are not solely limited to immunocompromised hosts and can be severe [1–3].

In this context, we present the first case report of prosthetic joint infection (PJI) caused by Kocuria rhizophila. Our paper discusses the current evidence base for the surgical and antimicrobial management of Kocuria-related infection.

CASE REPORT

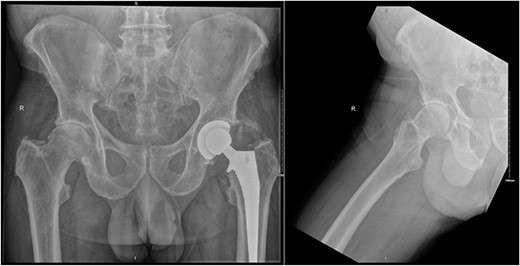

Our patient is a 74-year-old male who underwent primary total hip replacement for right hip pain. This was performed using a collared, fully hydroxyapatite-coated, uncemented stem, as well as an uncemented acetabular component with a ceramic-in-polyethylene bearing surface (Corail-Pinnacle, Depuy-Synthes, IN, USA). His recovery was uneventful until 6 weeks postoperatively when he presented to his routine outpatient appointment with significant erythema, swelling, and tenderness over his right hip wound. This was associated with difficulty weightbearing on the operative side due to discomfort. His background medical history included polymyalgia rheumatica for which he took Methotrexate 7.5 mg weekly, Folic acid 5 mg weekly, Celecoxib 200 mg BD, and pre-diabetes which was diet controlled. His other medical history included prostate cancer in remission since 2012, renal calculi, dyslipidaemia, and hypertension. He had a contralateral total hip replacement performed in 2020 (Fig. 1). He had no known drug allergies. At baseline, he was independently mobile. He was a non-smoker and non-drinker.

Preoperative AP pelvis and lateral right hip radiographs of our patient showing right hip osteoarthritis and previous left THR in situ.

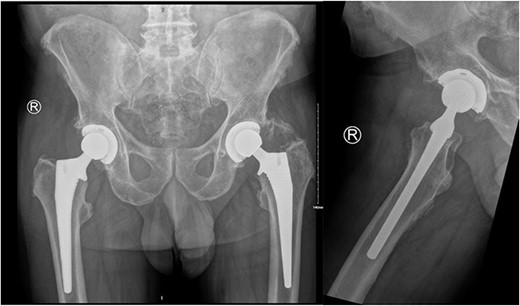

On examination, he had an antalgic gait and his range of motion was globally restricted due to pain. There was significant swelling and erythema over the operative site. His blood investigations demonstrated that his inflammatory markers were mildly elevated: white cell count (WCC) 8.5, CRP 14. X-rays showed satisfactory position of the implants (Fig. 2).

AP pelvis and lateral right hip radiographs 6 weeks post primary right THR when our patient presented with clinical signs of PJI. The implants were in a satisfactory position.

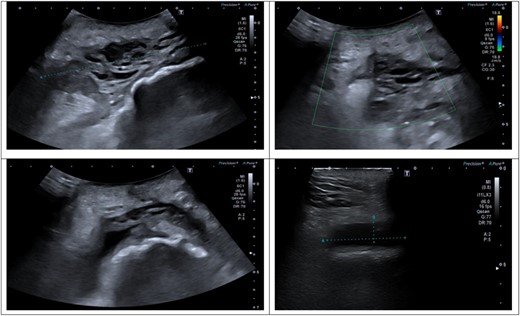

An ultrasound scan of his hip and thigh was performed which showed a large 10.1 cm × 4.3 cm, complex collection with mixed solid/cystic components. This was associated with a tract extending from the skin surface and a deeper fluid collection that tracked along the posterolateral right femoral shaft (Fig. 3). A subsequent CT femur with contrast reported a large collection adjacent to the greater trochanter with no evidence of fistulous communication with the joint. A separate locule of fluid 2.5 cm in length was seen superior to this and communicated with the main collection. There was no sign of prosthetic loosening or radiological evidence of osteomyelitis (Fig. 4).

(A–D) Ultrasound scan of right hip and thigh showing a large 10.1 × 4.3 cm complex collection with mixed solid/cystic components. There was no internal vascularity. This was associated with a tract extending from the skin surface and a deeper fluid collection that tracked along the posterolateral right femoral shaft. There was significant oedema of the subcutaneous tissue overlying the hip and thigh.

(A) Coronal, (B) Axial (C) Sagittal CT scan of right femur with contrast. The axial image is taken at the level marked on the coronal image. There is a large 8.3 cm × 4.5 cm × 4.5 cm collection seen adjacent to the greater trochanter with no evidence of fistulous communication with the joint. A separate locule of fluid 2.5 cm in size was seen superior to this and communicated with the main collection. There was no sign of prosthetic loosening or radiological evidence of osteomyelitis.

Based on the acuity of his symptoms and the radiological findings, it was determined that the patient should undergo debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention (DAIR procedure). This was performed through a lateral approach and all modular components of the implant were removed. Thorough washout and tissue debridement were performed. Postoperatively, the infectious diseases team advised starting IV Vancomycin and IV Piperacillin-Tazobactam empirically while awaiting the final culture results and sensitivity analysis.

Of the five intraoperative samples obtained, one sample of tissue from the lesser trochanter cultured K. rhizophila. This was identified by ‘Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry’ (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany). The remaining four samples were negative after extended culture and 16SRNA gene sequencing. A significant number of white cells, predominantly polymorphs were identified on the gram stains of all samples. Peripheral blood cultures were negative for growth after 14 days.

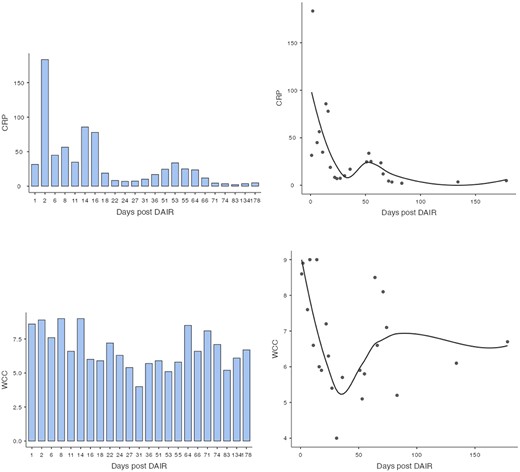

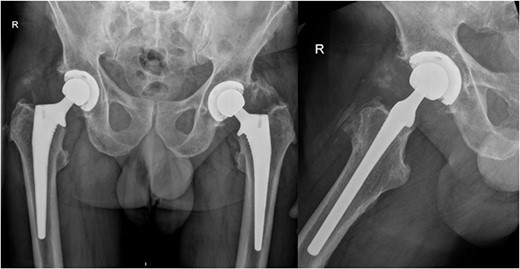

Subsequently, this patient’s case was discussed at our PJI multidisciplinary meeting among the infectious diseases, microbiology, and orthopaedic teams. A consensus decision was made to treat the patient with a 12-week course of IV Vancomycin given the clinical presentation, radiological, and intraoperative findings. After completing his 12 weeks of IV antibiotics, his inflammatory markers returned to normal limits (Fig. 5). At 6-month follow-up, our patient was mobilizing independently without any signs of infection recurrence. His radiographs showed the implant was in a satisfactory position with no evidence of loosening (Fig. 6).

Bar chart and scatterplot of CRP and WCC trends during postoperative period following DAIR procedure when IV antibiotics were started.

AP pelvis and lateral right hip radiographs at 6 months post debridement, antibiotics, implant retention (DAIR) procedure.

DISCUSSION

Kocuria species are classified within the Micrococcaceae family, which also includes the micrococcus and staphylococcus species. They are Gram-positive, coccoid bacteria that are typically aerobic, catalase-positive, and coagulase-negative [4]. Although Kocuria species were previously considered to be harmless commensals of the oropharynx and skin, there is a growing body of evidence to suggest their involvement in infections, especially among immunocompromised and co-morbid patients [1, 2, 5]. In the past, microbiological identification techniques were insufficiently advanced to accurately distinguish Kocuria and Staphylococcus species, resulting in an underestimation of the prevalence of Kocuria-related infections. Therefore, contemporary literature advises healthcare professionals against immediately dismissing these bacteria as contaminants as we develop our understanding of their pathogenicity [6].

Due to its rarity, our understanding of the clinical manifestations of Kocuria infection is still developing. Fortunately, the advancement of genetic identification techniques has facilitated a recent expansion in the literature describing cases of Kocuria infection [1]. Bhatnagar et al. describe a case of polymicrobial PJI as a result of Kocuria rosea and Mycobacterium Wolinskyi infection. This occurred in a 62-year-old man who presented with acute PJI, 6 weeks after bilateral total knee replacements. Interestingly, the initial culture - after aspiration of 15 ml of thick, translucent fluid - was negative for bacterial growth. The decision to proceed with a two-stage revision was based on the clinical presentation and minor diagnostic criteria for PJI as proposed at the International Consensus Meeting 2018 [7]. Samples taken during the first stage revision surgery grew K. rosea and the patient was treated with 6 weeks of IV Piperacillin-Tazobactam and Clindamycin followed by 6 weeks PO Clindamycin. Despite this treatment, the patient required a repeat first stage revision. Samples obtained during this surgery from sonication of the cement spacer grew M. Wolinskyi. The authors hypothesized that this was initially present but masked by the K. Rosea co-infection [8].

There have also been reports of catheter-associated bacteraemia, keratitis, native valve endocarditis, cholecystitis, peritonitis, necrotizing mediastinitis and brain abscesses caused by Kocuria species [2, 5, 9–12]. Being natural inhabitants of the skin, it is not unexpected that K. rosea and Kocuria kristinae have been most frequently described as causative agents of catheter-related bacteraemia [13–15]. Lai et al. outlined the characteristics of 21 isolates from 5 patients that were identified as Kocuria species. All four patients with K. kristinae infection had an implanted catheter. Interestingly, in previous reports of implant-related infection associated with Kocuria, several authors observed the necessity for catheter/line removal before the complete resolution of infection [13, 15]. This suggests that Kocuria species have a significant affinity to prosthetic material. Altuntas et al. have also raised concerns about the possibility of biofilm production associated with this species which would have a considerable impact on patient management. However, to date, there have been no proven cases of this in the literature [1, 14].

It is worth noting that there has been a rise in the cases that document severe infections and infections in immunocompetent hosts. Dunn et al. describe the case of a 29-year-old woman who was 16 weeks pregnant with no significant medical history. Their patient developed K. kristinae bacteraemia complicated by septic pulmonary emboli following insertion of a central line [3]. Lee et al. report the case of descending necrotizing mediastinitis in healthy 58-year-old woman that required surgical debridement and antibiotics [2]. Furthermore, Ma et al. report an otherwise healthy patient who underwent cholecystectomy for Kocuria infection associated with acute cholecystitis [9].

Our case describes the successful management of K. rhizophila through a combination of DAIR followed by a 12-week course of IV Vancomycin. Although the pooled success rate of DAIR for treating hip PJI is quoted as 70%, it is acknowledged that success is influenced by multiple factors [16]. Patient selection is therefore crucial, as highlighted by Qasim et al. who identified specific criteria for achieving favourable outcomes with DAIR. These include acute hematogenous infection, presence of Staphylococcus epidermidis or other low virulence bacteria, complete modular exchange, and the involvement of a multidisciplinary team [17].

Similar to our antibiotic choice, other case reports have described successful treatment of Kocuria species using monotherapy with oxacillin, vancomycin, piperacillin/tazobactam and ciprofloxacin and combination therapy with teicoplanin and vancomycin, ciprofloxacin and clindamycin as well as ceftriaxone and ofloxacin [13, 15, 18]. There are few very articles that report or examine the sensitivity profile of Kocuria species. One report of 219 strains of Kocuria and Micrococcus found that the majority of strains exhibit susceptibility to doxycycline, ceftriaxone, cefuroxime, amikacin, and amoxicillin with clavulanic acid. However, they are typically resistant to ampicillin and erythromycin [19]. Becker et al. reported that K. rhizophila isolated from a paediatric patient with sepsis was found to be solely resistant to Norfloxacin. Several other resistant strains have been reported in the literature without significant overlap among patients that would enable us to confer a pattern [6].

Lai et al. noted that although it is challenging to derive conclusive inferences about the most effective antibiotic treatment based on our limited data, their study suggest that clinical microbiology laboratory can accurately identify these uncommon bacteria to the species level, which is critical due to the distinct drug susceptibility patterns observed among different Kocuria species [13].

CONCLUSION

This case adds to an emerging body of literature describing invasive infections associated with Kocuria species. Our patient is the first reported acute PJI caused by K. rhizophila infection. We have demonstrated the effectiveness of managing this condition with debridement, implant retention, and IV Vancomycin therapy for 12 weeks. Additionally, this case emphasizes the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration when managing PJI, particularly as the incidence of atypical and multiply-resistant bacteria continues to rise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the microbiology department and laboratory scientists at our hospital for their contributions to the investigation and analysis of the clinical specimens involved in this patient’s case.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Timothy McAleese: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

Aathir Ahmed: Corresponding author, Data curation, Writing—original draft.

Mark Berney: Data curation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing.

Ruth O’Riordan: Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

May Cleary: Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Approval was not required for the writing of this case report. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

References

- antibiotics

- vancomycin

- inflammatory markers

- edema

- diagnostic radiologic examination

- debridement

- communicable diseases

- erythema

- follow-up

- hip region

- hip joint

- outpatients

- infections

- hip joint prosthesis

- hip replacement arthroplasty

- hip pain

- prosthetic joint infections

- antibiotic therapy, intravenous

- consensus

- joint infections

- implants