-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Santiago A Endara, Gerardo A Dávalos, Elizabeth Zamora E, Ligia M Redrobán, Gabriel A Molina, ‘Chest gossypiboma after spinal surgery, not so easy to forget’, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 6, June 2023, rjad328, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad328

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

During any surgical procedure, complications may arise, some of which are fortuitous, whereas others, unfortunately, occur because of errors of the surgical team. Fortunately, most are minor and do not affect the patient’s recovery, but others can cause severe morbidity and even mortality. A retained cotton or gauze surgical sponge inadvertently left in the body during an operation is known as a gossypiboma. This dreadful oversight is a marked complication that can cause serious postoperative complications, a severe economic burden on the healthcare system, and many medicolegal implications. We report the case of a 30-year-old male, who suffered a spinal fracture which was repaired through an anterior fixation approach 12 years ago in a local state hospital without complications. Suddenly, he presented with chest pain and cough, and sought medical attention. An 8 × 5 × 8 cm low-density heterogeneous mass was discovered on his chest; after successful surgery, a gossypiboma formed by several gauzes without radiopaque markers was discovered.

INTRODUCTION

Occasionally, some complications are inevitable during surgery, resulting in patient morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. However, some complications are the result of human error [1]. One of these is cotton or gauze retention, which results in what is known as gossypiboma [2]. Gossypiboma can be present in any body cavity, resulting in hospitalization, reoperation and mortality [1, 2]. The time to diagnosis can vary from a few hours to years after the event, as patients may remain asymptomatic for a long time [1, 2, 3]. Here, we present the case of a 30-year-old male; a gossypiboma was discovered in the thorax 12 years after repair of a vertebral fracture, and during this time, he remained asymptomatic. After surgery, he recovered completely.

CASE REPORT

The patient is an otherwise healthy 30-year-old male; at 18, he suffered a motorcycle accident with spinal cord injury and a thoracic fracture repaired in a local state hospital through an anterior fixation approach without complications. Afterward, he had normal development and had no problems after surgery. Suddenly he presented with acute pain in his upper right back; at first, the pain was mild and irrelevant to the patient; nonetheless, after 3 months, the pain became intense and was accompanied by severe episodes of nonproductive cough; therefore, he presented to the emergency room.

On clinical evaluation, a healthy young man was encountered. His vital signs were normal, and he had no episodes of dyspnea on excretion, fever, nausea or vomiting, but mild pain was discovered on palpation on his right upper back. Small clicking, bubbling and rattling sounds were also found on auscultation on his right thorax; therefore, a chest X-ray was requested.

A 6 × 3 cm opacity with several mottled small air densities on his right chest was discovered. With these findings, a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was requested.

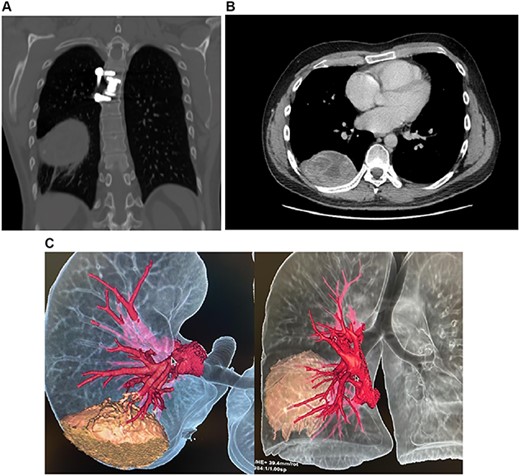

An 8 × 5 × 8 cm low-density heterogeneous mass with a spongiform pattern containing air bubbles and well-defined borders was discovered in the right posterior mediastinum. No lymph nodes or other masses were found (Fig. 1A–C). Gossypiboma, thymomas, lymphomas, germ cell tumors and neurogenic neoplasms were among the differential because of this, cardiothoracic assessment was needed and surgery was decided.

(A) CT, mass is seen in the posterior mediastinum attached to the right lung lobe. (B) CT, spongiform pattern is identified within the mass in the thorax. (C) 3D reconstruction of the CT scan, the mass can be identified in close contact with the lung.

A right posterior thoracotomy was completed, the lung was tractioned and many adhesions were released from the posterior aspect of the right upper pulmonary lobe. Once adequate exposure was achieved, an 8 × 5 × 8 cm mass was discovered closely attached to the spinal plate. The mass had a whitish color and was surrounded by a thick fibrous capsule. While removing it, we discovered that the mass was formed by several gauzes and neither of them had any radiopaque markers (Fig. 2).

Completely excised mass formed by several gauzes without radiopaque markers.

The mass was completely removed, a chest tube was placed and surgery was completed without complications. Pathology reported retained surgical gauzes surrounded by a fibrous capsule.

His postoperative course was uneventful. He fully recovered and was discharged on a postoperative 5 five after a short course of broad-spectrum antibiotics. On follow-ups, he is doing well without complications and is planning a legal process with his previous physician.

DISCUSSION

Retained surgical items, including sponges, gauzes and surgical equipment, are considered ‘never event’, meaning that this preventable complication should never happen [1]. It is named ‘gossypiboma’, derived from the Latin Gossypium meaning cotton wool and the suffix oma, meaning a tumor [1]. The estimated incidence can be between one in 1000 and one in 10 000 surgeries [1, 2]. Yet, this is an underestimation because this event accounts for more than 50% of all malpractice claims making it underreported [1, 3]. Many risk factors have been described and can be related to the procedures (emergency procedures, lengthy procedures and unexpected procedure changes), to the patients (patients with a high body mass index), to the staff (shift changes, staff’s inadequate communication and incomplete count of surgical gauze) and finally to the hospital (absence of a counting policy and usage of nonradiopaque sponges) [1, 3, 4].

Symptoms will depend on the location of the gossypiboma and the body’s inflammatory reaction against the foreign object; they can appear in the early postoperative period or very late, even several years after the event [2, 4]. In the early period, acute problems such as abscesses and infections occur, but in the late period, chronic issues such as obstruction and pain because of adhesions are encountered. Yet, a small subset will be completely asymptomatic and will only be diagnosed incidentally [1, 4, 5].

These events are most frequently reported after laparotomy and are extremely rare after thoracic surgery [6, 7, 8]. Nonetheless, it can occur as a primary event after thoracic surgery or as a migration of a foreign body through the diaphragm into the thorax. But, again, this is unusual with few cases presented in the literature [1, 5], as we found in our patient.

When symptomatic, the clinical presentation of an intrathoracic gossypiboma is broad and nonspecific, and preoperative diagnosis is challenging since patients may present with fever, cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, expectoration or wound discharge—mimicking other conditions, including malignancies. Therefore, gossypiboma must always be included in the differential, especially in patients who previously had thoracic surgery [1, 3]. In our case, our patient presented with chest pain years after his surgery.

Imaging is necessary for the diagnosis, and an X-ray is usually the first step as it can unveil an opacity with a visible radiopaque marker; however, CT is the most effective tool to diagnose intrathoracic gossypiboma correctly since it can detect the characteristic spongiform appearance of these tumors (mixed high- and low-attenuation contents with gas bubbles in the center); nonetheless, this sign can be missed as the pleura absorption could make the air bubbles disappear, and the CT may only show a nonspecific solid mass with peripheral contrast enhancement [1, 9]. Magnetic resonance imaging and transthoracic or transesophageal ultrasound can also be used to establish relationships with other surrounding organs [1, 3, 10]. In our case, the CT scan revealed the spongiform mass, and although many other pathologies were in the differential, his previous surgery and its imaging findings made us suspect a gossypiboma.

Surgery is the only treatment and should be performed as soon as possible to prevent pain, sepsis, fistulas and even death [1, 11]. This event is one of the worst safety violations causing severe morbidity, mortality and medicolegal problems, and is simultaneously a preventable condition [12]. Therefore, every surgical team must have appropriate communication with each other, using radiopaque markers on their gauzes and lap sponges and acting with standardized policies to count them. In our hospital, gauzes and lap sponges have radiopaque markers, and we routinely request a chest X-ray after finishing closure of the thoracotomy or sternotomy wounds.

CONCLUSIONS

Prevention of gossypiboma is far better than cure since these patients can have severe complications that can affect an otherwise successful surgery. Therefore, it must be remembered that careful examination of the surgical area before the closure, constant team communication, adherence to counting protocols and a high level of awareness are essential practices in every surgery.

As surgeons, patients’ health and safety must be our main priorities. Therefore, improving our awareness in the operating room is paramount to prevent this dreadful human error.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All data is available to the Editor on request.