-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dimitri Tchienga, Elliot Banayan, Micheal Arulin, Genato Romulo, Armand Asarian, Philip Xiao, Management of epididymal leiomyosarcoma: literature narrative, case report and discussion on the use of simple epididymectomy or high radical orchiectomy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 4, April 2023, rjad165, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad165

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Epididymal leiomyosarcomas are rare malignant tumors of smooth muscle origin. We present a case of a low-grade tumor with negative margins managed with a high-radical inguinal orchiectomy. Our review of the literature suggests that low-grade and localized tumors with negative margins can be managed with simple epididymectomy and imaging surveillance.

INTRODUCTION

Leiomyosarcomas (LMS) of the testes can be classified into paratesticular (about 217 reported cases) and intratesticular. Up to 80% of paratesticular LMS arise from the soft tissue of the spermatic cord, whereas 20% originate from the epididymis or darts of the scrotum [1]. LMS are further classified as cutaneous LMS that derive from the arrector pili muscle of the hair follicle or the dartos muscle of the genital skin and subcutaneous LMS that originates from the smooth muscle of the genital organ or the vascular muscle layer of subcutaneous tissue [2, 3]. Despite their origins, high-radical orchiectomy remains the preferred surgical management. Though curative, it can impair patients’ sexual lives. Simple tumorectomies have less sexual dysfunction and can provide good disease control [2–5]. This paper discusses when to use a simple epididymectomy or a high-radical orchiectomy for managing epididymal tumors.

CASE PRESENTATION

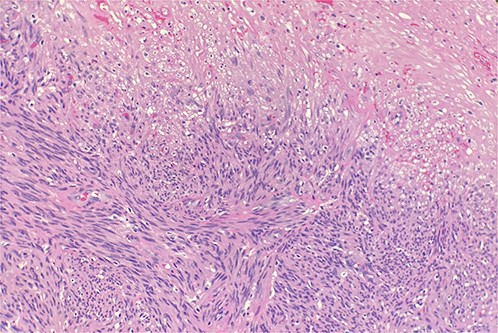

A 70-year-old male patient with a history of prostatic adenocarcinoma presented with testicular swelling. Testicular ultrasound revealed a 4 cm hypoechoic mass at the level of the epididymis. The patient underwent a radical orchiectomy. Pathology demonstrated a 4 cm mass located around the epididymis that was composed of elongated spindle cells arranged in intersecting fascicles. The tumor cells were found to have cigar-shaped nuclei and fibrillary eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 1). Most of the lesions indicated relatively monomorphic cytology. Scattered moderate-to-focally marked nuclear pleomorphism was present. Focal necrosis was present, which may be suggestive of more aggressive biologic behavior. Ki 67% was approximately 10% and the mitotic activity was 7 mitotic figures per 10 high power-fields. The tumor margins were negative, with no invasion of the testicular parenchyma or spermatic cord. Immunohistochemistry showed strong reactivity with desmin and smooth muscle actin (Fig. 2). Overall, findings were diagnostic of low-grade leiomyosarcoma.

Microscopic examination reveals intersecting fascicles of monotonous spindle cells with indistinct borders, eosinophilic cytoplasm and cigar-shaped nuclei. There is necrosis on the right upper portion. Hematoxylin and Eosin 20×.

Immunohistochemical stain reveals tumor cells are positive for smooth muscle actin. Immunohistochemistry 40×.

DISCUSSION

In general, LMS are managed with a high-volume radical orchiectomy, which provides negative margins, a low recurrence rate and a high survival rate [6]. A negative effect of a radical orchiectomy is a reduced postoperative testosterone level [6], which may, in part, explain why 22.5% of patients post-orchiectomy experience one type of sexual disorder [7], including but not limited to erectile or ejaculatory dysfunction [8]. In our case, we used a radical orchiectomy. When the pathological report classified our tumor as a low-grade leiomyosarcoma, we decided to investigate whether it was possible to perform a simple epididymectomy and obtain the same clinical benefits of a radical orchiectomy while reducing the risk of sexual dysfunction.

Bhatt et al. performed an analysis of 66 cases of malignant epididymal tumors from the United States (1975–2016). LMS constituted 23% of all those cancers, and they reported up to 35% of cancer-specific deaths from epididymal cancer. Of that 35%, 25% were due to leiomyosarcoma. About 66% of the tumors underwent either a partial or radical epididymectomy, and 50% received adjuvant therapy (chemotherapy or radiotherapy). After a 10-year follow-up, it was reported that the overall survival was 85% and the cancer-specific survival was 91%. The authors attribute these findings to the benign nature of the majority of the tumors (78%), and the combination of the treatment modalities. Given the high survival rate, we can infer that an epididymectomy can provide good disease control. Previous case reports of paratesticular LMS also demonstrated good disease control with a simple tumorectomy [2–5].

When comparing simple tumorectomy with high-radical orchiectomy in the setting of subcutaneous vs. cutaneous paratesticular tumor management, we found both techniques offered no significant difference in terms of local recurrence, disease metastasis and disease-specific survival [6]. Though both surgical approaches achieve similar local recurrence rates, in a subgroup of subcutaneous LMS, simple tumorectomy had a significantly increased risk of local recurrence compared to high-radical orchiectomy [6]. Therefore, ultrasound, computed tomography chest or magnetic resonance abdominopelvic surgery is recommended post-resection. Kamitani et al. identified age or positive margins and size or tumor grade as variables that significantly increase the risk of local recurrence and disease metastasis, respectively.

Since the two surgical approaches offer the same clinical benefits, we would like to suggest a two-step approach based on the findings above. First, define through a simple epididymectomy the stage of the tumor. If low grade and negative margins were achieved, follow up with imaging surveillance. Hence, patients will avoid the adverse effects of a radical orchiectomy. However, if a high-grade tumor is suggested or negative margins are not obtained, proceed with a radical orchiectomy.

Management of high-grade (2–3) tumors (high mitotic index) seldom requires adjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy or retroperitoneal lymph node dissection [6, 9–12]. Radiotherapy has decreased the local recurrence rate in patients who receive orchiectomy [11]. Regarding chemotherapy, there are questionable survival benefits [10], whereas retroperitoneal lymph node dissection was not shown to be beneficial. Adjuvant therapies have negative effects on libido, intensive orgasm, maintaining an erection and volume of semen [7]. The decision and choice of adjuvant therapy should be thoroughly evaluated, and a clear clinical benefit must be seen before putting patients through unnecessary experiences.

We recognized that our paper has some limitations that are directly linked to those reported in the primary retrospective analysis papers. Among the limitations are sample bias, small sample size, unmeasured confounding variables, publication bias and insufficient clinical data. Further studies are recommended to further evaluate the claims made on this topic.

CONCLUSION

This review highlights the possibility, when the patient has a localized epididymal leiomyosarcoma, of performing an epididymectomy followed by pathological staging. If low grade and negative margins were achieved, proceed to image surveillance. If a high-grade tumor or positive margins are demonstrated, proceed to a high-inguinal radical orchiectomy. Surveillance is paramount, with radiation therapy being beneficial if recurrence happens.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.