-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Elizabeth Skalkos, Jason Diab, Christophe Berney, Female with multiple groin pathologies: inguinal hernia containing fallopian tube, obturator hernia and subcutaneous endometrioma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 3, March 2023, rjad155, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad155

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Groin lumps in females can be challenging due to unique anatomy and vast differential diagnostic pathologies. We report the case of a 39-year-old female presenting with a six-month history of painful left groin lump. Laparoscopic total extraperitoneal (TEP) hernia repair showed an incarcerated left indirect inguinal hernia sac containing part of the left fallopian tube and fimbrial cyst, a left fat-containing obturator hernia and associated with ectopic subcutaneous inguinal endometrioma. The anatomical differences in women suggest that individualized preoperative imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging have a place before considering laparoscopic hernia repair, to successfully identify and synchronously treat any concomitant pathologies.

INTRODUCTION

A groin lump appearing as a swelling at the inguinofemoral junction is a common surgical presentation in general practice and emergency departments. The clinical features of a groin mass vary in size, shape, tenderness and consistency, reflecting various possible underlying pathological processes, including hernias, infection, neoplasms, vascular or congenital abnormalities [1, 2]. Groin hernias occur 9–12 times more frequently in males and only 9% of all hernia operations occur in females [3, 4]. Females have a unique set of diagnostic challenges due to anatomical differences compared to males, inconspicuous examination findings, and non-specific ultrasound imaging findings. We herein report the case of a 39-year-old female with a left groin lump, which revealed multiple concomitant pathologies intraoperatively including an incarcerated indirect inguinal hernia containing part of the left fallopian tube, subcutaneous inguinal endometrioma and an occult left obturator hernia.

CASE REPORT

A 39-year-old woman presented to a general practitioner with a painful left groin lump. She had experienced six months of intermittent left groin pain exacerbated by walking and associated with menstruation. Her past medical history included gestational diabetes mellitus and no previous surgery. She had no regular medications and was a non-smoker. She had a normal body mass index. On examination, there was a firm, non-reducible and tender left groin mass. The abdomen was otherwise soft and non-tender. There were no contralateral masses and no inguinal lymphadenopathy bilaterally. An ultrasound showed a 33 × 25 × 29-mm sized hypoechoic irregular area within the left groin with some increased vascularity.

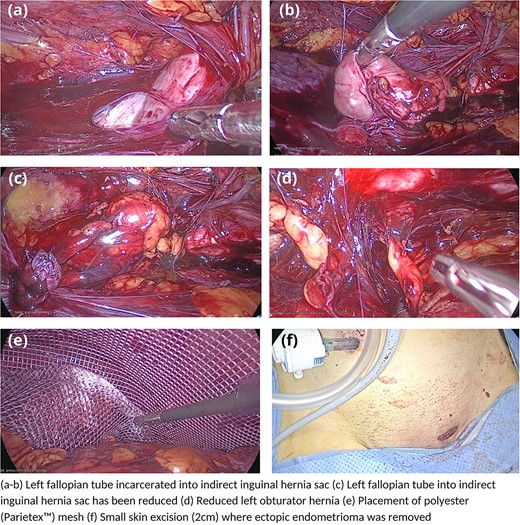

She was referred to a general surgeon. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a left-sided direct inguinal hernia containing omental fat with a hernial neck measuring 2 cm without lymphadenopathy. She was consented for an elective laparoscopic total extraperitoneal (TEP) mesh repair of symptomatic left inguinal hernia. Intraoperative findings included an incarcerated left indirect inguinal hernia sac containing part of the left fallopian tube and fimbrial cyst, an ectopic subcutaneous inguinal endometrioma and an incidental occult fat-containing left obturator hernia (Fig. 1). Consistent with the senior surgeon’s approach, the hernias were reduced laparoscopically, including division of the round ligament, and a pre-shaped anatomical Parietex™ mesh was inserted covering all important structures from pubic symphysis towards the space of Bogros, and fixed with fibrin glue along its inferior border [5]. The subcutaneous endometrioma was excised through a separate 2-cm skin incision. Postoperative recovery was uneventful, and she was discharged the following day. Histopathology of the subcutaneous mass confirmed extensive areas of endometriosis. The patient’s preoperative symptoms had resolved at two weeks and two months follow-up.

Laparoscopic images demonstrating incarcerated left fallopian tube, left obturator hernia, microscopic endometrioma and Parietex™ mesh placement.

DISCUSSION

Accurate preoperative diagnosis of groin masses in females can be a diagnostic challenge, yet important to guide management. These differences may be in part due to our selected understanding of groin hernias being predominantly derived from male cohorts given their lifetime risk is 27–43% compared to only 3–6% in females [6]. Females have differentials exclusive to their anatomy, including inguinal endometriosis, canal of Nück hydrocele, round ligament lipomas and varicosities. These can be clinically indistinguishable to commoner groin hernias on examination and less routinely considered given their paucity. Other key anatomical distinctions contribute to increased risk of specific pathologies including femoral hernias, related to the wider female pelvis and atrophy of an already smaller mass of protective muscle bulk, and also obturator hernias postulated to be a result of a more horizontal direction of the obturator canal [7].

A British study of 183 female groin hernia repairs demonstrated misdiagnosis in 18.3% [8]. Two other studies showed a significantly increased risk of incidental hernias found during laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery in females compared to males (29.2 vs 2.2%, and 37 vs 3%, respectively) [9, 10]. Higher rates of hernia recurrence in females are also thought related to misdiagnosis of the primary pathology [3]. Differentiating between common and uncommon pathologies has implications for management (laparoscopic vs open) and the timing of surgery (emergency vs elective). The HerniaSurge Group advises supplementation of clinical examination with ultrasound in females with groin masses to improve pre-operative diagnosis [3]. Ultrasound can differentiate hernia from other pathologies and evaluate for hernia-related complications; however, findings can be non-specific, operator dependent and occult hernias can be missed, as in our case [11]. Where diagnostic uncertainty remains, MRI offers improved specificity in differentiating groin lumps with higher sensitivity than ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) [11]. MRI is the best diagnostic tool to diagnose musculoskeletal pathologies including adductor tendonitis, pubic osteitis or extrapelvic endometriosis, where identification of hemosiderin deposits is pathognomonic [11, 12]. Access and costs of MRI are challenging, so CT can be utilized when ultrasound is negative and MRI is not available [3]. Nevertheless, imaging may remain non-diagnostic, as in this case of multiple pathologies. This is consistent with another case report of histologically proven subcutaneous inguinal endometrioma and inguinal hernia, where preoperative ultrasound and CT identified a right ovarian cyst and homogeneous hypoechoic lesion, without inguinal hernia [13].

The recommended surgical approach for females with groin hernias considers the challenge of preoperative diagnosis. A preperitoneal laparoscopic approach is recommended, setting up a thorough view of the myopectineal orifice, allowing for assessment of all hernial orifices [3, 8]. Interestingly, other case reports describe an open approach in females with multiple concomitant groin pathologies, although these would not identify concomitant hernia or contralateral pathologies, unlike in this case [13–15]. We believe that routine laparoscopic TEP approach in females allows for better identification and appropriate management of multiple pathologies not identified preoperatively.

CONCLUSION

Females presenting with inguinal hernia may harbor multiple concomitant hernia defects, or other rarer groin pathologies. A sound understanding of reproductive anatomy and clinical imaging can guide surgeons to make better tailored decisions pre-operatively and utilize their technical skills to address the pathologies, preferably in a minimally invasive manner.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No authors have competing interests.

FUNDING

None declared.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors contributed to the conception and design of the manuscript, revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data are deemed confidential and under ethics cannot be disseminated openly due to confidentiality and privacy.