-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Paul Tonog, Derek T Clar, Nicole Ebalo, Ovie Appresai, Single stage surgical management of a sigmoid gallstone ileus case, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 3, March 2023, rjad135, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad135

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Bowel obstruction/ileus is a relatively common occurrence in surgical practice with a predictable clinical presentation and management course. Rarely are these cases found consistent with gallstone etiology. Known as gallstone ileus (GI), this uncommon presentation is found primarily in elderly females (age > 65 years old) with multiple comorbid conditions; usually with coinciding presence of a cholecystoenteric fistula. Surgical management remains controversial due to the rarity of presentation and complexity of related pathological process. We present a case of a 69-year-old female who presented with typical signs/symptoms of bowel obstruction but found to have sigmoid GI on computed tomography imaging evaluation. A single stage exploratory laparotomy with simple enterolithotomy was performed with a positive outcome and uncomplicated postoperative recovery. The primary goal in reporting this case is to continue emphasizing the efficacy of a single stage simple enterolithotomy as the most ideal surgical management of this rare condition.

INTRODUCTION

Gallstone ileus (GI), described as the mechanical impaction of a gallstone in the bowel lumen resulting in obstruction, is a rare complication of cholelithiasis with an estimated prevalence of 0.15–1.5% of all gallstone related disease [1]. These cases are primarily reported in elderly females (average age 65–75 years old) with multiple comorbid conditions [2] and typically presents as a bowel obstruction. Classically the diagnosis was confirmed by a plain film triad, known as Rigler’s triad (pneumobilia, ectopic radio-opaque stone and bowel obstruction), which has now been adapted to computed tomography (CT) due to higher sensitivity in identifying components of said triad and offers accuracy in locating the bowel obstruction and measurement of stone size [3].

Inherent to location of the ileocecal valve to biliary tree, most cases of GI can result in obstruction of the small bowel [4]. Rarely is the reported incidence of stone impaction/ileus in the colon at ⁓3–4% [1] with the coinciding presence of a cholecystocolonic fistula documented in only 5–25% of all colonic GI cases [2]. Definitive management remains surgical with the goals of stone extraction and prevention of recurrence [5]. The known surgical approaches are based on a single stage versus a two-stage model, a discussion that has remained controversial [1]. The options for single stage have been described as either a simple enterolithotomy or the more complex enterolithotomy/cholecystectomy/fistula closure, whereas the two stage is described as an enterolithotomy and delayed cholecystectomy with fistula closure [5]. Results have varied among these approaches with the most worrisome complication being recurrence which has been reported in 2–5% of cases, with the higher risk being in those with the uncorrected fistula [1]. Based on morbidity and mortality; however, the simple enterolithotomy has been found to be the safest and most effective surgical approach with lowest mortality rate [3].

We present a rare case of an elderly female who presented in distributive shock due to a large bowel obstruction as result of sigmoid GI. This patient underwent a successful single stage simple enterolithotomy with an uncomplicated recovery and no indication of recurrence despite not addressing a coexisting cholecystocolonic fistula. The main goal of reporting this patient’s clinical course is to continue emphasizing the benefits of a simple single stage technique as the most efficacious and safe management of these complex cases.

CASE REPORT

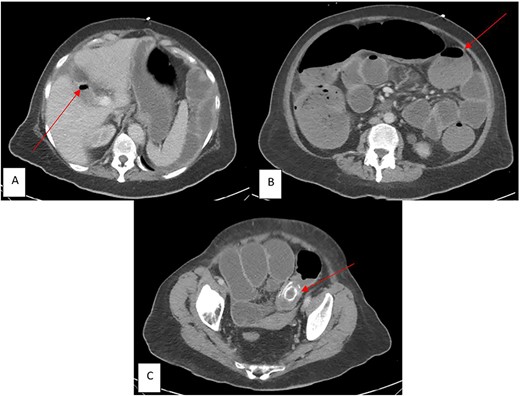

A 69-year-old Caucasian female presented to our institution with a chief complaint of abdominal pain with accompanying nausea, vomiting and constipation for ⁓1 week. Patient was noted to have multiple co-morbidities: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), and a recent middle cerebral artery (MCA) ischemic stroke. Vitals were significant for body temperature of 36.7°C, blood pressure was 91/56 mmHg, and pulse rate was 104 beats/min. On a physical exam, the patient displayed tenderness to palpation in the left lower quadrant of her abdomen with abdominal distention and tympany to percussion. Laboratory studies significant for leukocytosis [white blood cell count (WBC) 16.2 u/L] and electrolyte abnormalities (Potassium 3.0 mEq/L, Chloride 102 mEq/L). CT revealed pneumobilia (Fig. 1A), multiple distended loops of bowel consistent with obstruction (Fig. 1B), and a 3.6 × 2.1 cm, high-density structure within the lumen of the distal sigmoid colon indicating impacted gallstone (Fig. 1C). Based on these clinical findings, the patient was diagnosed with sigmoid GI. Considering the risk of perforation and patient’s hemodynamic instability, an emergent laparotomy was performed.

CT imaging in the emergency department (ED) with components of Rigler’s Triad (marked by red arrows): (A) Pneumobilia, (B) distended loops of bowel consist with large bowel obstruction, (C) gallstone impacted in the sigmoid colon.

Laparotomy revealed distended loops of small bowel leading up to the sigmoid colon. The stone was palpable in the mid sigmoid. A colotomy was performed over the stone which was removed from the lumen. The colotomy was then closed in two layers with absorbable/Vicryl suture. The original surgical plan was to intervene on both the stone and fistula, though due to increasing requirement of vasopressor (norepinephrine, vasopressin) support as the procedure progressed, a decision was made just to perform the enterolithotomy. Following laparotomy, the patient was able to have return of bowel function by postoperative day (POD) 2, while being monitored in the intensive care unit and was discharged on POD 4. Final pathology was consistent with a gallstone that measured 4.5 × 2.6 × 2.2 cm in dimension and weight of 23 g. In total, ⁓3 weeks post-procedure, this patient was seen in the clinic with no further complaints of ileus and no recurrence of gallstone related disease.

DISCUSSION

This case highlights how a case of sigmoid GI induced obstruction can be successfully managed with a simple surgical intervention. Our patient had the classic presentation of being an elderly female with multiple comorbid conditions and cardinal symptoms of bowel obstruction. Due to coinciding hemodynamic instability, identifying components of Rigler’s triad via CT (Fig. 1A–C) was paramount in prompt diagnosis and decision-making to take emergently for intervention. As stated, there was thought of addressing both stone removal and fistula closure but as the patient was requiring higher vasopressor support, a decision was made to forego fistula closure. This appeared to be the most beneficial route as the patient’s recovery and hospitalization was brief and uncomplicated with no indication of recurrence on outpatient follow-up. Our case gives credence to the simple procedure being an adequate intervention for patients that present in severe shock, offering a safer procedure that outweighs the risk of GI recurrence.

Successful non-surgical approaches in those presenting with colonic GI have also been reported. Cases highlighting spontaneous evacuation of gallstones have been documented [6], although would likely not have suited our patient as most of those studies appear to involve small bowel GI. Specific to colonic GI, a more conservative intervention would be extraction via colonoscopy [3], with some case reports documenting successful endoscopic extraction of a sigmoid stone with adjunct intervention of lithotripsy [7]. Though these more conservative approaches are theoretically safer, in a recent systematic review of 38 sigmoid GI cases only 26% were successfully managed without need of surgical intervention [8]. Unfortunately, there remains too limited data of above conservative management as an efficacious approach [3] and so wouldn’t have benefitted our patient at the time of her presentation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no known and/or potential conflicts of interest in respect to the information used in the publication of this case report.

FUNDING

None.