-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dong Tony Cheng, Thomas Young, Paul Mercedes Kim, Dimitrios Nikolarakos, Airway emergency after dental extraction, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 3, March 2023, rjad082, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad082

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Life-threatening airway emergencies and uncontrolled haemorrhage following dental extractions is rarely encountered. Inappropriate handling of dental luxators may lead to unexpected traumatic events resulting from penetrating or blunt trauma to the surrounding soft tissues and vascular damage. Bleeding during or after surgery usually resolves spontaneously or with local haemostatic interventions. Pseudoaneurysms are rare occurrences secondary to blunt or penetrating trauma usually produced by arterial injury leading to extravasation of blood. The rapidly enlarging haematoma with risk of spontaneous pseudoaneurysm rupture is an airway and surgical emergency necessitating urgent intervention. The following case highlights the importance of appreciating the potential complications associated with extractions in the maxilla, significant anatomical relationships and recognizing the clinical signs of a threatened airway.

INTRODUCTION

Life-threatening airway emergencies and uncontrolled haemorrhage following dental extractions is rarely encountered. Inappropriate handling of dental luxators may lead to unexpected traumatic events resulting from penetrating or blunt trauma to the surrounding soft tissues and vascular injury. The following case highlights the importance of appreciating the vascular complications associated with maxillary extractions and recognizing the clinical signs of a threatened airway.

CASE REPORT

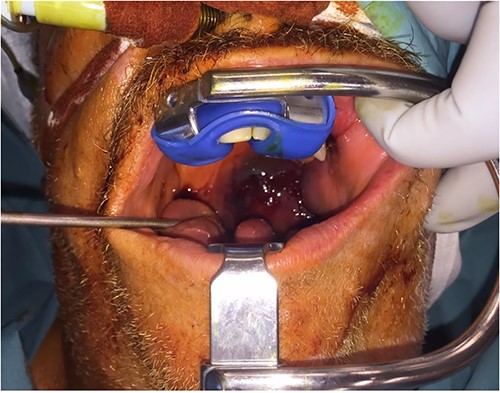

A 61-year-old male with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department complaining of swallowing difficulties. The patient was unable to tolerate secretions or speak in full sentences and seated in a forward leaning position. A local dentist had earlier performed a surgical extraction of an upper left permanent first molar with inadvertent instrument slippage to the palate. The patient reported severe projectile haematemesis within the hour of returning home. On immediate return to the dentist, local haemostatic measures decreased bleeding but resulted in an increased left palatal swelling. In the resuscitation bay, the patient was febrile to 38.3 deg, hypertensive 180/100 and tachypnoeic to 28 breaths per minute. Limited examination revealed a large palatal haematoma with no active arterial bleeding and midline uvula displacement. The threatened airway and the risk of haematoma rupture led to the decision for immediate transfer to theatre for surgical intervention. The patient underwent an awake fibre-optic nasal intubation, and a tonsil retractor was placed for visibility (Fig. 1).

Nasal intubation, with Boyle Davis retractor in situ revealing expansile left palatal haematoma crossing midline.

Examination under anaesthesia revealed a left palatal haematoma obliterating the oropharynx with extension medially and inferiorly to the base of the tongue. A large palatal flap was raised for access with frank arterial bleeding noted. Visibility was further improved with decompression of the haematoma bulk via a curvilinear mucosal incision over the left soft palate. The reduction in mass effect allowed further elevation of the palatal flap and identification and ligation of the left greater palatine artery (GPA). Haemostasis was completed with bipolar diathermy and FLOSEAL® application. Post-operatively, the patient remained intubated, was admitted to intensive care and administered IV dexamethasone 8 mg. The patient had significant interval reduction of the haematoma, was successfully extubated after 24 h and discharged home at 48 h. Outpatient review at Day 10 post-surgery revealed no subjective or functional deficits (Fig. 2), and further recovery was uneventful.

Significant interval improvement at Day 2 post (left) and Day 10 post (right).

DISCUSSION

Modern dental luxating elevators have extremely thin sharp tips which can be inserted between the root surface and alveolar bone. The instrument can be used as a wedge, using apical force to transect the periodontal ligament, expand periradicular bone laterally and to displace the tooth coronally [1]. Iatrogenic soft tissue and vascular injuries perioperatively are usually self-limiting and resolved with local haemostatic measures. In one study of post-operative complications associated with 161 upper third molars extractions, there were no cases of haematomas or bleeding in the perioperative period [2], while another study noted bleeding occurred in 0.16% of cases [3].

The blood supply of the maxillary palate is comprised of a complex anastomotic network of arterial branches supplied mainly from the maxillary, facial and ascending pharyngeal arteries originating from the external carotid artery. The maxillary artery gives off the descending palatine artery as it traverses the pterygopalatine fossa to become its terminal branches of the greater (GPA) and lesser palatine arteries (LPA) in their respective foramina. The GPA emerges from the greater palatine foramen at the junction of the alveolar process of the maxilla and the horizontal plate of the palatine bone located on the hard palate between the second and third maxillary molars at ~3 mm from the osseous crest and 18–20 mm from the occlusal plane [4]. A systematic review investigating 5768 hemipalates using combined data from cadaveric and radiological imaging found the distance from the GPA to the cementoenamel junction of the maxillary first and second molar were 13.0 +/− 2.4 mm and 13.9 +/− 1.0 mm, respectively. Additional arterial supply is given by the maxillary artery via the sphenopalatine branch and the posterior superior alveolar branch (PSAA), the facial artery via an ascending palatine branch and the ascending pharyngeal artery via the palatine branches. The arterial supply of the soft palate is mainly supplied by the anterior and posterior branches of the ascending palatine artery.

A pseudoaneurysm is an extravascular haematoma that has developed secondary to blunt or penetrating trauma contained only by the outermost vessel layer of tunica adventitia. Haematoma formation occurs due to continued arterial extravasation and gradual expansion of the perivascular tissues. They are distinguished from true aneurysms, which are bound by all three layers of the arterial wall and are thus, at a higher risk of rupture. Computed tomography angiography can be used to accurately assess the true size of the aneurysm and clinically triage the urgency of treatment required. Pseudoaneurysms can be managed with open surgical ligation or percutaneous transluminal arterial embolization with various agents such as gelatin sponge plugs, platinum coils or polyvinyl alcohol particles. This patient could not complete diagnostic imaging due to the threatened airway and risk of spontaneous pseudoaneurysm rupture. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of a traumatic pseudoaneurysm involving the GPA after dental extraction. To date, a total of 16 cases of pseudoaneurysm complications following dental extractions, six of those involving maxillary teeth have been reported. All except one were treated by arterial embolization (Table 1) [5]. The period of time from extraction to embolization varied considerably from 5 h to 5 weeks, which provides some guidance to clinical urgency [3]. However, the most critical component of management is the recognition of the threatened airway and the impending pseudoaneurysm rupture. Red flag symptoms such as tachypnoea, dysphagia, dyspnoea and inability to tolerate oral secretions should prompt the clinician to consider a threatened airway.

| Authors – Year . | Age/Sex . | Extracted teeth (FDI notation) . | Arterial source . | Treatment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sakamoto et al. [6] – 1991 | 21 M | 18 | PSAA | Embolization |

| Koga et al. [7] – 2005 | 48 F | 48 | IAA | Embolization |

| Maeda et al. [8] – 2007 | 84 F | 47 | IAA | Embolization |

| de Lucas et al. [9] – 2008 | 25 M | 38 | Facial | Embolization |

| Benazzou et al. [10] – 2009 | 71 M | 28 | PSAA | Embolization |

| Stiefel et al. [11] – 2010 | 39 M | 27 | PSAA | Embolization |

| Rayati et al. [5] – 2010 | 35 M | 35 | Facial artery | Surgery |

| Pham et al. [12] – 2011 | 51 M | Multiple | Bilateral IAA, | Embolization |

| Pukenas et al. [13] – 2012 | 20 M | 38 | PSAA, facial artery | |

| Facial IAA | Embolization | |||

| Wasson et al. [14] – 2012 | 60 M | 38 | IAA | Embolization |

| Sagara et al. [3] – 2013 | 24 M | 38 | IAA | Embolization |

| 37 F | 38 | IAA | ||

| 29 M | 48 | IAA | ||

| 24 F | 48 | PSAA | ||

| 26 M | 18 | PSAA | ||

| Rawat et al. [15] – 2019 | 24 M | 18 | PSAA | Embolization |

| Authors – Year . | Age/Sex . | Extracted teeth (FDI notation) . | Arterial source . | Treatment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sakamoto et al. [6] – 1991 | 21 M | 18 | PSAA | Embolization |

| Koga et al. [7] – 2005 | 48 F | 48 | IAA | Embolization |

| Maeda et al. [8] – 2007 | 84 F | 47 | IAA | Embolization |

| de Lucas et al. [9] – 2008 | 25 M | 38 | Facial | Embolization |

| Benazzou et al. [10] – 2009 | 71 M | 28 | PSAA | Embolization |

| Stiefel et al. [11] – 2010 | 39 M | 27 | PSAA | Embolization |

| Rayati et al. [5] – 2010 | 35 M | 35 | Facial artery | Surgery |

| Pham et al. [12] – 2011 | 51 M | Multiple | Bilateral IAA, | Embolization |

| Pukenas et al. [13] – 2012 | 20 M | 38 | PSAA, facial artery | |

| Facial IAA | Embolization | |||

| Wasson et al. [14] – 2012 | 60 M | 38 | IAA | Embolization |

| Sagara et al. [3] – 2013 | 24 M | 38 | IAA | Embolization |

| 37 F | 38 | IAA | ||

| 29 M | 48 | IAA | ||

| 24 F | 48 | PSAA | ||

| 26 M | 18 | PSAA | ||

| Rawat et al. [15] – 2019 | 24 M | 18 | PSAA | Embolization |

IAA inferior alveolar artery, PSAA posterior superior alveolar artery

| Authors – Year . | Age/Sex . | Extracted teeth (FDI notation) . | Arterial source . | Treatment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sakamoto et al. [6] – 1991 | 21 M | 18 | PSAA | Embolization |

| Koga et al. [7] – 2005 | 48 F | 48 | IAA | Embolization |

| Maeda et al. [8] – 2007 | 84 F | 47 | IAA | Embolization |

| de Lucas et al. [9] – 2008 | 25 M | 38 | Facial | Embolization |

| Benazzou et al. [10] – 2009 | 71 M | 28 | PSAA | Embolization |

| Stiefel et al. [11] – 2010 | 39 M | 27 | PSAA | Embolization |

| Rayati et al. [5] – 2010 | 35 M | 35 | Facial artery | Surgery |

| Pham et al. [12] – 2011 | 51 M | Multiple | Bilateral IAA, | Embolization |

| Pukenas et al. [13] – 2012 | 20 M | 38 | PSAA, facial artery | |

| Facial IAA | Embolization | |||

| Wasson et al. [14] – 2012 | 60 M | 38 | IAA | Embolization |

| Sagara et al. [3] – 2013 | 24 M | 38 | IAA | Embolization |

| 37 F | 38 | IAA | ||

| 29 M | 48 | IAA | ||

| 24 F | 48 | PSAA | ||

| 26 M | 18 | PSAA | ||

| Rawat et al. [15] – 2019 | 24 M | 18 | PSAA | Embolization |

| Authors – Year . | Age/Sex . | Extracted teeth (FDI notation) . | Arterial source . | Treatment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sakamoto et al. [6] – 1991 | 21 M | 18 | PSAA | Embolization |

| Koga et al. [7] – 2005 | 48 F | 48 | IAA | Embolization |

| Maeda et al. [8] – 2007 | 84 F | 47 | IAA | Embolization |

| de Lucas et al. [9] – 2008 | 25 M | 38 | Facial | Embolization |

| Benazzou et al. [10] – 2009 | 71 M | 28 | PSAA | Embolization |

| Stiefel et al. [11] – 2010 | 39 M | 27 | PSAA | Embolization |

| Rayati et al. [5] – 2010 | 35 M | 35 | Facial artery | Surgery |

| Pham et al. [12] – 2011 | 51 M | Multiple | Bilateral IAA, | Embolization |

| Pukenas et al. [13] – 2012 | 20 M | 38 | PSAA, facial artery | |

| Facial IAA | Embolization | |||

| Wasson et al. [14] – 2012 | 60 M | 38 | IAA | Embolization |

| Sagara et al. [3] – 2013 | 24 M | 38 | IAA | Embolization |

| 37 F | 38 | IAA | ||

| 29 M | 48 | IAA | ||

| 24 F | 48 | PSAA | ||

| 26 M | 18 | PSAA | ||

| Rawat et al. [15] – 2019 | 24 M | 18 | PSAA | Embolization |

IAA inferior alveolar artery, PSAA posterior superior alveolar artery

Life-threatening airway emergencies and major arterial haemorrhage as complications of surgical extractions are extremely rare in the dental setting. Early medical help should be sought when conventional local haemostatic measures are unsuccessful. This case has shown the importance of the recognition of an acute vascular injury and the clinical signs of a threatened airway.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

No funding sources.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The above proposal has been reviewed by the Chair’s Delegate of the GCHHS Human Research Ethics Committee and deemed not requiring HREC review on the basis that it is a case study.

PATIENT CONSENT

Patient consent was obtained.