-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sunao Ito, Ryo Ogawa, Masayuki Komura, Shunsuke Hayakawa, Tomotaka Okubo, Hiroyuki Sagawa, Tatsuya Tanaka, Akira Mitsui, Satoru Takahashi, Shuji Takiguchi, Severe esophageal stricture after perforation and necrotizing esophagitis: unusual presentation of a duodenal gastrinoma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 12, December 2023, rjad679, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad679

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gastrinomas are pancreatic or duodenal endocrine tumors that secrete excess gastrin, which causes gastroesophageal reflux disease, peptic ulcers, and chronic diarrhea. Due to the rarity of the disease, nonspecific symptoms, and the outstanding effect of proton pump inhibitors, diagnosing gastrinomas is difficult. Here, we present the case of a 58-year-old woman who had a duodenal gastrinoma that caused rare but critical events, including esophageal perforation, necrotizing esophagitis, and severe esophageal stricture. She presented with a non-malignant severe lower esophageal stricture, which was resistant to endoscopic dilatation. During esophagectomy, a duodenal mass was excised and diagnosed as gastrinoma. This was considered the main cause of all events. Gastrinomas are rarely encountered in clinical practice, but early diagnosis is necessary to avoid serious conditions. Therefore, whenever we encounter a patient with gastroesophageal reflux disease requiring long-term treatment or is refractory, we must not forget to screen for gastrinomas.

Introduction

Gastrinomas are pancreatic or duodenal endocrine tumors that secrete excess gastrin [1]. Excessive gastrin causes the stomach to hyperproduce gastric acid, which can result in Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. The main symptoms of Zollinger–Ellison syndrome are gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), peptic ulcer, and chronic diarrhea [2, 3]. However, in recent years, the number of mild to asymptomatic cases has increased because of the widespread use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) [2]. Therefore, diagnosing gastrinomas is difficult. Due to the rarity of the disease, nonspecific symptoms, and the outstanding effect of PPIs, the median time from onset to correct diagnosis is as long as 5.2 years [3]. We encountered a case of duodenal gastrinoma that caused esophageal perforation, necrotizing esophagitis (NE), and severe esophageal stricture. This case indicates the importance of screening for gastrinomas in patients with GERD requiring long-term treatment and/or refractory symptoms.

Case report

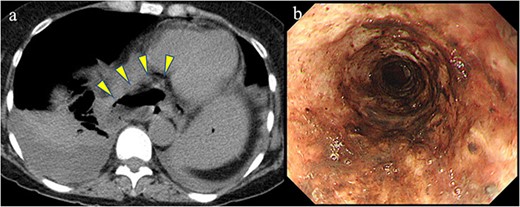

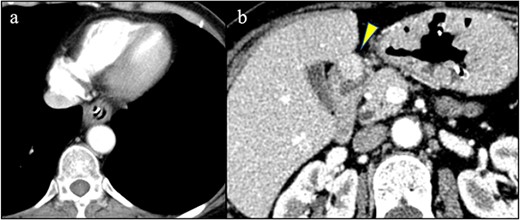

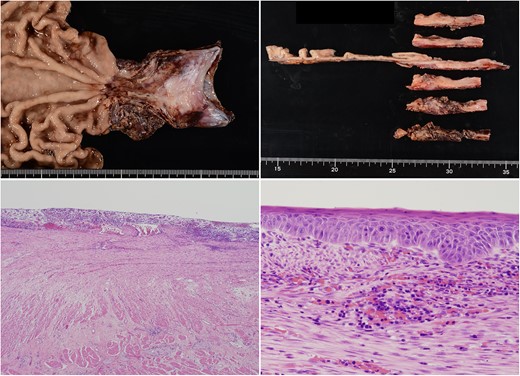

A 58-year-old woman with severe stricture of the lower esophagus was referred to our institution. She had been receiving medication to treat GERD at multiple facilities for the past 5 years. Six months prior to the referral, she underwent laparoscopic esophageal repair for esophageal rupture (Fig. 1a). After the rupture, she eventually presented with NE (Fig. 1b), a condition that consequently led to severe stenosis of the lower esophagus (Fig. 2). Multiple biopsies did not confirm any malignancy in the esophagus, and endoscopic balloon dilatation temporarily enabled endoscopic observation of the gastro-duodenum, which had no significant abnormal findings, but failed to relieve the constriction. Computed tomography revealed a 10-mm hypervascular mass on the anterior wall of the duodenum, suggestive of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (Fig. 3); there were no findings suggestive of esophageal malignancy. Pathological diagnosis of the duodenal mass could not be determined because the endoscope used for endoscopic ultrasound-fine needle aspiration could not pass through the esophageal stricture.

Previous conditions of the esophagus. Esophageal rupture accompanied by a massive mediastinal abscess (arrowheads). Necrotizing esophagitis of the lower esophagus.

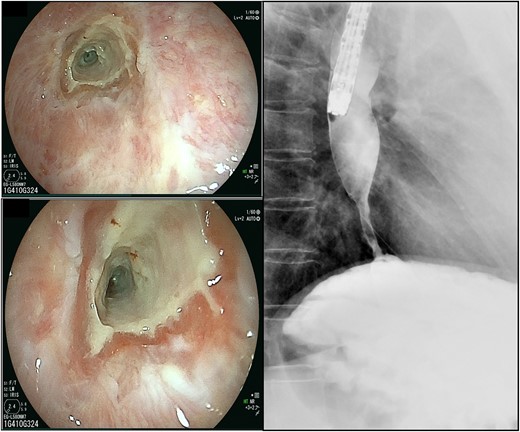

The scars continued down the esophagus, extending beyond 23 cm from the incisors, while the lower esophagus to the gastroesophageal junction was severely constricted.

(a) No findings in the esophagus suggested malignancy. (b) A hypervascular mass was detected on the anterior wall of the duodenum (arrowhead).

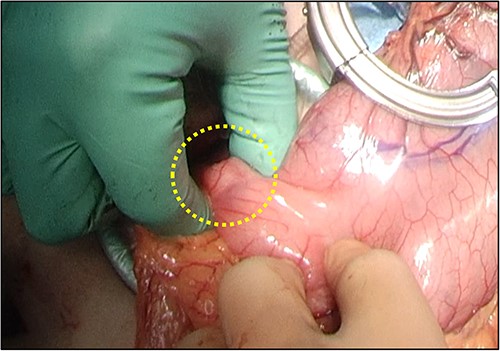

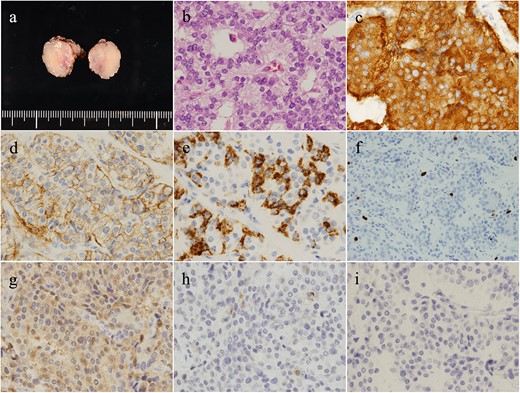

Overall, the esophageal stricture was determined to be benign and resistant to endoscopic treatment; thus, surgical resection of the esophagus was scheduled. She underwent thoraco-laparoscopic subtotal esophagectomy, followed by gastric tube reconstruction via the posterior sternal route. During mini-laparotomy to prepare the gastric tube, partial duodenectomy was performed for excisional biopsy of the duodenal mass (Fig. 4). Postoperatively, the patient had no morbidities.

Partial duodenectomy was performed to resect the duodenal mass during mini-laparotomy.

Pathologically, the severely constricted esophagus was determined as a benign lesion with inflammation (Fig. 5). Conversely, the duodenal mass was indicated as a grade 1 neuroendocrine tumor. Additional immunostaining confirmed the diagnosis of gastrinoma (Fig. 6).

The constricted esophagus had a circumferential loss of squamous epithelium and a high degree of inflammatory cell infiltration. Residual squamous epithelium showed enlarged nuclei; it was determined to be reactive atypia associated with inflammation.

The duodenal tumor (a) presented a rosette-like, trabecular-patterned proliferation of cells with round nuclei in the muscularis propria (b). Tumor cells were synaptophysin (+) (c), CD56 (+) (d), and chromogranin A (±) (e). MIB-1 index was 1.8%, and the mitotic count was 2/10 per high power field (f). Additional immunostaining presented gastrin (+) (g), somatostatin (±) (h), and insulin (−) (i). Altogether, the tumor was diagnosed as gastrinoma.

Based on the pathological diagnosis, further investigations ruled out multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, and an octreotide scan showed no residual tumor. At 1 month postoperatively, the serum gastrin level was 510 pg/ml, which was lower than the 1200 pg/ml measured immediately after surgery.

The gastrinoma is considered to be completely resected and is currently under careful observation. Although she is still taking PPIs, her food intake is satisfactory, and no reflux symptoms are reported.

Discussion

We encountered a case of duodenal gastrinoma in which rare but critical events occurred. The patient had overcome esophageal perforation, NE, and severe esophageal stricture, all caused by GERD due to gastrinoma.

In retrospect, a couple of factors caused difficulty in diagnosing gastrinoma. First, GERD is a common disease; incidence rates are reported to be 20% in Western countries [4] and 15% in Japan [5]. Clinicians know that gastrinomas cause GERD syndromes, but are rarely encountered in routine practice; therefore, it is not a disease to be routinely ruled out. Moreover, the most commonly used drugs for the treatment of GERD are PPIs, which inhibit the final step of gastric acid secretion and can even control gastrinoma symptoms [6]. For clinicians who had treated the patient at an early stage, reaching the diagnosis of gastrinoma from GERD symptoms masked by PPIs would have been quite difficult.

Second, when referred to our institution, she already had severe esophageal stricture. After ruling out malignancy, we speculated that esophageal rupture and the accompanying mediastinal abscess critically damaged the lower esophagus, and further exposure to gastric acid due to GERD resulted in NE, subsequently leading to severe constriction. At that time, it did not occur to us to investigate the background disease of GERD that had already been diagnosed elsewhere and for which treatment had already been initiated. In addition, since the findings of gastroduodenal ulcer and episodes of chronic diarrheal symptoms were not evident, it was difficult to include gastrinoma in the differential diagnosis.

However, clues to the correct diagnosis were still present. She required long-term treatment for GERD, and GERD requiring long-term treatment should be suspected to have an underlying gastrinoma. It is not certain for how long the duodenal mass had been present, but if it had been linked to GERD symptoms, the diagnosis of gastrinoma would likely have been made earlier, before esophageal perforation, or at least before esophageal stricture had occurred.

In conclusion, gastrinomas are rarely encountered in clinical practice, but we wish to note that early diagnosis is necessary to avoid serious conditions. Therefore, whenever we encounter a patient with GERD requiring long-term treatment or is refractory, we must not forget to screen for gastrinomas. Furthermore, when clinicians encounter lower esophageal strictures that are not caused by cancer, GERD and an underlying gastrinoma should be considered as the cause.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for the English language editing.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared for the confidentiality/privacy of the patient involved.

Ethical approval

All the procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions.

Consent for publication

The patient provided informed consent for publication of this case report.