-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nadica Draskacheva, Darko Saljamovski, Violeta Gošić, Gjorgji Trajkovski, Gligor Ristovski, Shqipe Misimi, Andrej Nikolovski, When is surgery indicated in metastatic small intestine neuroendocrine tumor?, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 10, October 2023, rjad580, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad580

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Small intestine neuroendocrine tumors are predominantly small but with high potential for distant metastases development. Diagnosis establishment in early-stage is often difficult and challenging. Small intestine neuroendocrine tumors often initially present with liver metastases. According to the Consensus Guidelines of the North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society, in patients with liver metastases from unknown origin of primary neuroendocrine tumor, surgical exploration should be performed in order to identify the primary location, prevent small intestine obstruction, and treat one if already present. We present a case of a 69-year-old male patient diagnosed with liver and peritoneal metastases due to small bowel neuroendocrine tumor treated with surgery due to the presence of small intestine obstruction.

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors are the third most common neoplasia in the gastrointestinal tract with incidence of 0.29 per 100 000 habitants. Small intestine neuroendocrine tumors (SI-NETs) are the most common small bowel malignancy. They are usually small in size, but with high potential for distant metastases. Therefore, just a minority of patients present with local disease [1, 2]. We present a case of a male patient diagnosed with massive liver metastases from neuroendocrine tumor of initially unknown origin accompanied with intestinal obstruction.

Case report

This report presents the case of a 69-year-old male patient who presented with weight loss (≈15 kg) over a period of 2 months, loss of appetite for the past 18 months, occasional flushing, cramp abdominal pain (over past 2 weeks), and abdominal right upper quadrant pain in the last 2 months. Reported previous comorbidities comprehended arterial hypertension and atrial flutter. Abdominal ultrasound showed presence of secondary metastatic deposits in both liver lobes, which was confirmed by magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the liver. Percutaneous liver biopsy followed. Immunofluorescence was found to be positive for Chromogranin A (ELISA) with value of >850 ng/ml (referent value <100 ng/ml). Additional immunohistochemistry stain results showed positivity on Chromogranin and CD56, Ki-67 index of proliferation 2–3% (G1/nG1) with conclusion for metastatic neuroendocrine liver deposit existence with unknown primary location.

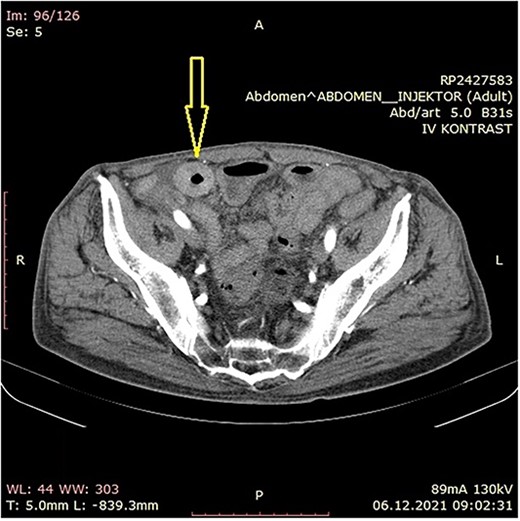

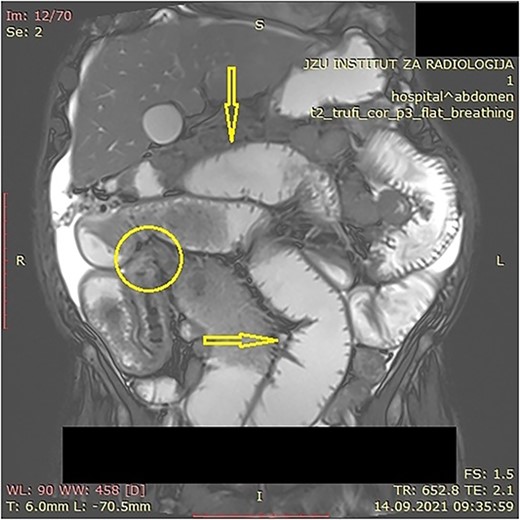

The patient was initially treated with monthly intramuscular doses of 20 mg of octreotide LAR (long-acting somatostatin analog) over a period of 5 months. During this period, the patient subsequently developed gradual partial small bowel obstruction, manifested with episodes of cramp abdominal pain and difficulties in bowel movement. Abdominal computerized tomography (CT) scan and MR imaging enterography were indicated. CT scan confirmed the presence of liver metastases and thickened small bowel wall with no confirmation of primary tumor existence (Fig. 1). MR enterography revealed small bowel distension with visible zone of transition in the right hemi abdomen (ileum) with restriction of diffusion (low signaling of apparent diffusion coefficient map) with surrounding desmoplastic reaction and visible irregular tumor with measured dimensions of 24 × 18 mm (Fig. 2).

Abdominal CT scan showing small bowel wall thickening described as chronic small bowel obstruction (arrow).

MR enterography with dilated small bowel loops (arrows) and visible zone of transition with visual tumor in the ileum (encircled).

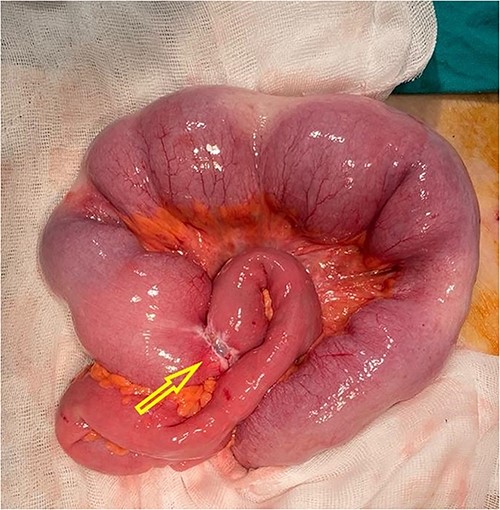

Explorative laparoscopy was offered to the patient in order to relief the symptoms and for primary tumor location confirmation. The procedure revealed the presence of massive peritoneal metastases (newly discovered finding) with ascites in addition to the liver metastases and small intestine obstruction at the level of ileum (Video 1). Conversion to open surgery followed due to insufficient laparoscopic exploration. During laparotomy, obstructive tumor (single lesion) of the ileum was discovered (Fig. 3). Partial resection of the involved small bowel segment with terminal ileostomy creation was performed. The postoperative period was uneventful and the patient was discharged on postoperative Day 4. However, the patient passed away 3 months after surgery.

Intraoperative finding with visual obstructive small bowel tumor (arrow).

Macroscopic pathologic finding of the resected bowel confirmed presence of nodular neoplasm with dimensions of 1.9 × 1 cm. It embraced 2/3 of the wall circumference with lumen stenosis of 70%. Intramural invasion with mesenteric infiltration (depth of 0.4 cm) was described. Two lymph nodes were detected in the resected specimen. Microscopic analysis verified the morphology of well differentiated neuroendocrine tumor of the small bowel. One of the isolated lymph nodes was positive for metastatic deposit. Tumor emboli were present in the lymph vessels. The reported mitotic activity was 2 mitoses on 10 high power fields.

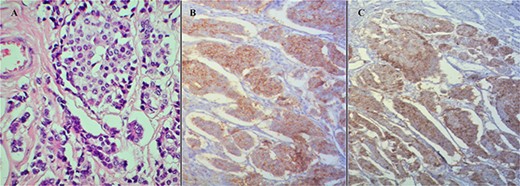

Additional immunohistochemistry showed positivity to Chromogranin, Synaptophysin, CD56, CDX2, NSE, and CKAE1/AE3 (wild type expression) (Fig. 4A–C). According to the Union for International Cancer Control (8th edition), final stage was pTNM = pT4, pN1, pM1C, Stage IV, pL1, pV0, pPn1, pR0.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain of the tumor. (B) Synaptophysin stain positivity. (C) Chromogranin stain positivity.

Discussion

Neuroendocrine tumors can appear elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract. According to frequency occurrence, most commonly affected organ is the stomach, presented with 23% of cases, the appendix being the second one with 21% and 15% incidence of the small intestine [3]. Male gender predominance was reported. The average age appearance is in the sixth and seventh decade of life [1].

Neuroendocrine tumors are rarest epithelial tumors with neuroendocrine differentiation and at the same time are the most common tumors of small intestine. Physiologically featured, the neuroendocrine cells deliver hormones upon stimulation by the nervous system and these hormones are distributed in specific organs, coordinating their function. In compliance with the pathophysiology of the disease, this hormone producing tumors are the most reciprocal with the carcinoid syndrome (flushing, cough, whizzing, diarrhea, carcinoid heart disease with heart dysrhythmia and heart failure), especially when the jejunum and the ileum are affected [4].

Due to the nonspecific symptoms, SI-NET diagnosis can often be delayed. In the early stages, dominant symptomatology is manifested with abdominal cramps, bloating, and intermittent diarrhea. Metastatic dissemination can appear even if the primary lesion is very small and still not diagnosed. Tumors >1.5 cm are usually metastatic at discovery. Multiple primary lesions are reported in 20% of the cases [3].

Due to the initial diagnostic difficulty of this entity, multidisciplinary approach is needed. In compliance with the pathophysiology, knowing that these tumors can produce and secret many substances, they can be measured and used for the diagnosis of the SI-NETs. Chromogranin A is a glycoprotein secreted by NETs, so it is a very specific and sensitive guide for diagnosis. 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid, a breakdown of serotonin, is measured with 24-hour urine collection [5].

As a prognostic factor, by the use of antigen Ki 67 (also known as MKI 67 or Marker of Proliferation Ki-67), the World Health Organization proposed classification and grading system for gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasia according to their differentiation. The group of well differentiated neoplasms consists of three grades: Grade 1 (Ki 67 index ≤3%), Grade 2 (Ki 67 index 3–20%), and Grade 3 > 20%. Poorly differentiated are described as G3 with Ki 67 index >20% [6].

Small intestine NETs cannot always be detected by the use of imaging methods, regardless of the anatomic or functional imaging method. The routine CT scan usually doesn’t have the ability for primary lesion detection. However, by use of the multidetector computed tomography, combined with water as an oral contrast, sometimes can detect small primary tumors. It can be useful for visualizing the mesenteric extension (in later arterial phase) of tumors and liver metastases. CT enterography combined with later arterial and venous phase has improved the sensitivity for diagnosing, showing the liver metastases in the later venous phase with IV contrast [7].

MRI has a higher sensitivity and more advantages from the CT scan. Liver metastases can be visualized and measured thus resulting in 95% sensitivity [7]. The reported overall sensitivity of MRI enterography for primary SB-NET is 74% on a per-lesion basis and 95% on a per-patient basis [8].

When the patient is being symptomatic, but without primary tumor finding, promising method is Osteoscan – somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, a functional imaging method using Indium pentetreoide. It allows excellent visualization on the primary NETs [7].

The recommended treatment for SI-NETs is resection of primary tumors, regional lymph nodes, and peritoneal carcinomatosis (if existed). Usually, the standard recommendations include explorative laparotomy with manual palpation of the small intestine to identify SI-NETs either small or multiple lesions. Although there is no high-grade evidence of surgical recommendations for SI-NETs accompanied with peritoneal carcinomatosis, cytoreductive surgery has shown a long-term survival for the patients. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis includes maximal surgical debulking combined with hyperthermic intraoperative chemotherapy [9].

In this case besides the advanced stage of the disease, long-term somatostatin analogs were recommended. Aggravating circumstance of bowel obstruction forced surgery involvement. To conclude, in patients with SI-NET accompanied with massive liver and peritoneal metastases and bowel dysfunction, surgery should be considered for symptomatic relief.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

All data is present in the manuscript.