-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jack Peter Archer, Nicholas Williams, Non-operative management of a large Morgagni hernia—an alternative approach?, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 1, January 2023, rjac614, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac614

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Morgagni’s hernia (MH) is a congenital diaphragmatic hernia with a small percentage of cases diagnosed in adulthood. The average age of diagnosis is 57 years, with 61% being female and 10–28% being asymptomatic. It is common practice to complete surgical repair of MH regardless of symptomology or size of the defect despite a paucity of evidence. This paper highlights the potential for non-operative management as a reasonable treatment option in large asymptomatic MH. A female in her 40s was referred following an abnormal spirometry result as a part of a routine pre-employment check. She subsequently had imaging, which showed a large MH with abdominal contents within the thoracic cavity. Following discussion at a multidisciplinary team meeting, it was decided that the risk of perioperative morbidity likely exceeded the risk of strangulation while asymptomatic, and thus surveillance was recommended.

INTRODUCTION

Morgagni’s hernia (MH) is a congenital diaphragmatic hernia with a small percentage of cases diagnosed in adulthood. Despite a paucity of evidence, it is common practice to complete surgical repair of MH in adults regardless of symptomology or size of the defect. This paper highlights the potential for non-operative management as a reasonable treatment option in large asymptomatic MH.

CASE REPORT

A female in her 40s was referred by her General Practitioner following an abnormal spirometry result as a part of a pre-employment check. She subsequently had a chest X-ray, which showed abdominal contents within the thoracic cavity.

The patient was well, asymptomatic and had no history of congenital abnormalities as a child. Her past medical history included seasonal asthma and an unprovoked deep venous thrombosis. There was no family history of congenital hernias. Her only regular medication was a salbutamol inhaler. She was a current smoker of 10-pack-year duration and lived a normal and active lifestyle. She reported no limitations on her physical activity or exercise capacity. Physical examination and routine blood tests were unremarkable, including full blood count, liver and renal function. The patient had no previous abdominal or thoracic imaging.

The spirometry results from her General Practitioner showed a restrictive pattern with FVC of 2.08L (55% predicted), FEV1 of 1.62L (54% predicted) and FEV1/FVC ratio of 0.78 (96% predicted). Her chest X-ray demonstrated a large hiatus or congenital hernia (Fig. 1). Subsequent computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen and pelvis showed a large 88 × 48-mm defect of the anterior diaphragm consistent with MH. Hernial contents extended to the superior mediastinum and were primarily large bowel and omentum, with no intestinal obstruction (Figs 2–4).

Posterior/anterior chest X-ray showing the reduced size of both lung fields and presence of abdominal contents in the chest cavity bilaterally.

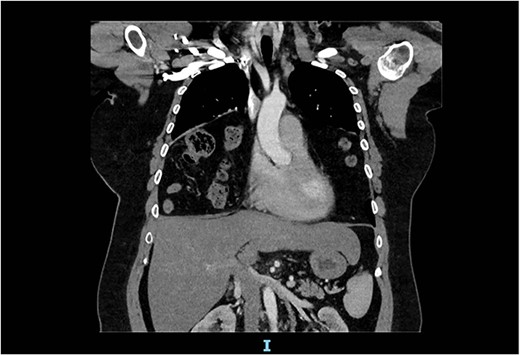

Arterial contrast CT of the chest. Coronal slice transecting the midpoint of the chest cavity showing herniation of large bowel, small bowel and omentum into the chest cavity.

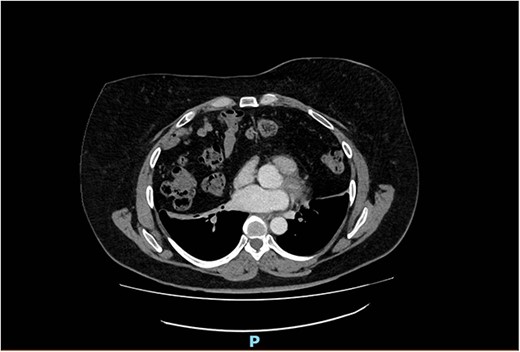

Arterial contrast CT of the chest. Axial slice at the T4/5 level showing herniation of large bowel, small bowel and omentum into the chest cavity. The defect in the anterior diaphragm measures 88.2 mm × 48.2 mm. Of note is the significant reduction in the size of the lung fields.

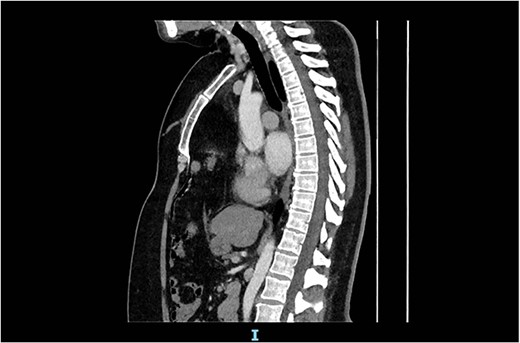

Arterial contrast CT of the chest. Sagittal slice in the midline of the body. The diaphragmatic defect is clearly seen anteriorly, and the abdominal contents are seen extending to the superior mediastinum.

The patient’s presentation was discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting. Given the large size of the hernia defect, the perceived risk of incarceration remained low. Given her lack of symptoms, young age and low risk of incarceration, a consensus was reached that the risk of perioperative morbidity likely exceeds the risk of strangulation, and thus surveillance was recommended whilst the patient remains asymptomatic. The patient agreed with this sentiment voicing a preference for non-operative management.

The patient was given smoking cessation advice, and an annual follow-up with her General Practitioner was recommended. She passed her pre-employment check and was advised that she had no restrictions on physical activity.

The patient remains asymptomatic and has experienced no issues secondary to her MH at follow-up 6 months after her initial review.

DISCUSSION

MH is a type of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) that Italian anatomist Giovanni Battista Morgagni first described in 1769 [1]. The defect occurs due to the failure of normal closure of the pleuroperitoneal folds [2]. CDH occurs in 1–4 per 100 000 births, with a slightly higher prevalence in males [3]. The most common locations of CDH diagnosed at birth are posterolateral (Bochdalek, 70–75%), anteromedial (Morgagni, 23–28%) and central (2–7%; [4]).

Nearly all cases of MH are now identified during embryological development on routine ultrasound scans at 18–22 weeks, with diagnosis in adulthood being extremely rare [5, 6]. A systematic review by Katsaros et al. identified 310 reported adult cases of MH from 1949 to 2020 [5]. In this paper, the average age at diagnosis was 57 years, with a female predominance (61%). Right-sided MH was the most common (84%), followed by left-sided (11.2%) and bilateral hernias (4.8%). This study identified that the average diameter of the hernial defect was 88 mm, with the most common hernia contents being the greater omentum (74.5%), transverse colon (65.1%), stomach (19.5%), liver (17.4%) and small intestine (15.8%).

Of CDH cases diagnosed in adulthood, only 10–28% are asymptomatic, primarily diagnosed incidentally on CT and X-ray imaging [5, 7]. If symptomatic, patients commonly present with abdominal pain (37%), shortness of breath (36%) and bowel obstruction (20%) [7].

Katsaros et al. and Horton et al. recommend surgical repair for all patients with MH due to concerns about intestinal strangulation; however, there is a paucity of data [5, 7]. Surgical repair can be performed from the abdominal or thoracic sides, and both open and minimally invasive techniques have been described [5, 7]. Of these procedures, laparotomy has the highest complication rate (17%) and the highest mortality (4%); however, the number of cases was low, and the case-mix of these patients was unknown [7].

Very limited evidence and case reports exist regarding the conservative management of MH in adults. Repeatedly it is cited that all MH should be repaired surgically due to the risk of strangulation, despite a paucity of evidence. However, based on this literature the recommended management in these cases remains preventative surgical repair [5, 7].

In the case described in this paper, it was deemed that the risk of perioperative morbidity likely exceeds the risk of strangulation, and thus surveillance was recommended. The patient also preferred non-operative management whilst remaining asymptomatic. The patient has remained asymptomatic for 6 months at the time of this paper and follow up will be continued to monitor progress. Future published case reports and series would contribute to our knowledge and understanding of this rare hernia.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have nothing to disclose.

FUNDING

None.

References

- adult

- employment

- patient care team

- perioperative care

- spirometry

- surgical procedures, operative

- abdomen

- diagnosis

- diagnostic imaging

- morbidity

- hernia of foramen of morgagni, congenital

- hernia, congenital diaphragmatic

- strangulation

- surveillance, medical

- thoracic cavity

- interdisciplinary treatment approach