-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Darren Turner, Daniel Nwatu, Karishma Kodia, Carlos Theodore Huerta, Nestor R Villamizar, Lawrence Briski, Dao M Nguyen, Middle mediastinal cavernous hemangioma: a case report of clinical, pathologic and radiologic features, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 5, May 2022, rjac230, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac230

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Benign vascular tumors of the mediastinum are rare, representing only 0.5% of all mediastinal masses. Given their rare presentation, they are infrequently considered in the workup of a middle mediastinal mass. We present a unique case describing the clinical, imaging and pathologic characteristics of a middle mediastinal cavernous hemangioma which was initially misdiagnosed as a bronchogenic cyst and ultimately required surgical resection with the use of veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

INTRODUCTION

Hemangiomas are benign vascular lesions that commonly occur in soft tissues [1]. Hemangiomas rarely present in the mediastinum [2]. Cavernous hemangiomas (CHMs), caused by congenital vascular dysplasia, occur most commonly in the anterior mediastinum of younger adults, followed by the posterior and middle mediastinum [3]. Given its rare presentation, CHMs in the middle mediastinum can be misidentified for benign lesions such as bronchogenic cysts, which are commonly found in the middle mediastinum.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 29-year-old female presented to the thoracic surgery clinic in April 2017 after incidental discovery of a middle mediastinum cystic lesion at an outside hospital. She was asymptomatic at the time of presentation. Computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large, cystic lesion posterior to the superior vena cava and lateral to the trachea and esophagus, measuring ~5.1 × 4.8 cm, suggestive of a bronchogenic cyst. Surgical resection was scheduled; however the patient was lost to follow up in the interim.

The patient ultimately presented again in March 2020, with symptoms including chest and neck pain, dysphagia and dyspnea at rest that began a few days prior to presentation. On physical exam, the patient was tachypneic and tender to palpation on the right side of her neck, chest and back. CT angiogram demonstrated an 8 cm × 10 cm × 7.4 cm non-enhancing, low-attenuation mass in the right middle mediastinum extending to the right superior mediastinum, abutting the medial aspect of the right lung apex causing significant external compression of the distal trachea (Fig. 1).

CT axial and coronal views demonstrating the right middle mediastinal mass (8 cm × 10 cm × 7.4 cm) with distal tracheal extrinsic compression.

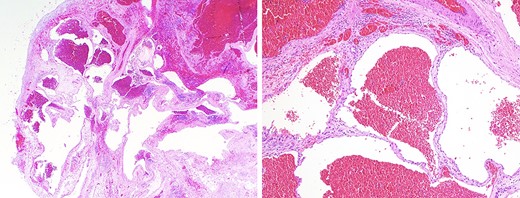

Given her compressive symptoms, interventional radiology (IR) was consulted to drain the presumed cyst to decrease the mass effect on the trachea and allow for safe intubation prior to surgical resection. The procedure was aborted, however, as dense material suggestive of blood clot was encountered by the IR team and there was little free fluid that was able to be drained. Given the significant tracheal compression and risk of difficult intubation, the surgical team coordinated with the extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) team to electively place the patient on veno-venous (VV)-EMCO prior to intubation as previously described [4]. Bilateral femoral veins were cannulated with 23F cannula with VV-ECMO flow initiated at 4 L/min. The patient was subsequently intubated and single lung isolation was obtained. The patient was placed in left lateral decubitus and the case proceeded with a right posterolateral muscle-sparing thoracotomy. Upon encountering the mass, large blood clots were evacuated to decompress the lesion followed by resection; no feeding vessels or point of origin was noted. Estimated blood loss was 100 cc. The patient was decannulated off the ECMO circuit at the end of the case; the duration of ECMO was ~5 h. The decision was made to keep the patient intubated overnight for planned mechanical ventilation and she was extubated without issue in the intensive care unit on postoperative day 1. There was no postoperative clinical tracheomalacia noted. The rest of her clinical course was unremarkable, and she was discharged on postoperative day 5. Final pathology revealed a benign mediastinal hemangioma with intra-cavitary hemorrhage (Fig. 2).

(a) low-power microscopic view (hematoxylin and eosin stain; 20X magnification) showing a well-circumscribed tumor composed of ectatic blood-filled spaces separated by intervening fibrous stroma with scattered lymphoid aggregates, entrapped fat and smooth muscle proliferation; (b) medium-power microscopic view (hematoxylin and eosin stain; 100X magnification) highlighting the presence of endothelial cells lining blood-filled spaces, confirming the diagnosis of a benign hemangioma.

DISCUSSION

Benign vascular tumors of the mediastinum are rare, largely described in case reports, with fewer than 110 cases reported [5]. Mediastinal hemangiomas comprise only 0.5% of mediastinal masses [2]. As such, little data exist on their management and long-term follow-up care. The majority of CHMs present in the anterior mediastinum and least frequently in the middle mediastinum [3]. The mean age of patients diagnosed with CHMs is 35 years old [5].

Clinically, patients with CHMs are usually asymptomatic and the lesion is incidentally diagnosed on imaging [6]. Presentations can include compressive symptoms with tumors that infiltrate adjacent structures causing dysphagia, chest pain or fullness, dyspnea, hemoptysis or superior vena cava syndrome. Our patient was asymptomatic at her index presentation and initial diagnosis was thought to be a bronchogenic cyst given the low-attenuation mass based on CT scan findings [7].

CHMs have some characteristic imaging findings. Contrast-enhanced CT is particularly useful for the detection of mediastinal vascular tumors. Radiographic features include descriptions of an enhancing mass or associated organized thrombi that calcify as phleboliths in 10% of cases [8, 9], more likely to be found on CT as compared with MRI [10]. MRI may also show a ‘fast in, slow out’ phenomenon of peripheral mass enhancement in the arterial phase with delayed central regional filling [7, 10]. On MRI, these tumors are hypointense on T1W1 and hyperintense on T2W1 with especially high signals on T2W1 fat suppression serving as an important identifying criterion [11]. Both CT and MRI may be needed to suggest a diagnosis of CHM.

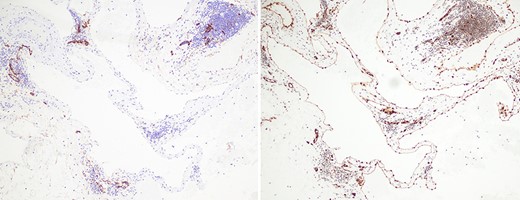

Despite imaging, it may be difficult to differentiate mediastinal hemangiomas from other lesions of the mediastinum without the aid of histopathological confirmation. Histologic features divide hemangiomas into three types: capillary hemangiomas, CHMs, which encompass 90% of cases, and a mixed type [12]. Fig. 2a and2b demonstrates low and medium power views of the lesion, highlighting the presence of endothelial cells lining blood-filled spaces, intervening fibrous stroma, and scattered lymphoid aggregates, diagnostic for CHM. Immunohistochemistry staining was positive for ERD, CD-31, CD-34, confirming a hemangioma and negative for D2-40, effectively ruling out lymphangioma (Fig. 3a and3b).

(a) immunohistochemical staining with antibodies for ERG, an endothelial marker, shows strong and diffuse nuclear positivity in the lining cells of the ectatic blood-filled spaces, confirming the diagnosis of a hemangioma (100X magnification); (b) immunohistochemical staining with antibodies for D2-40, a lymphatic marker, is negative in the lining cells of the ectatic blood-filled spaces, effectively ruling out the differential consideration of a lymphangioma (100X magnification).

Surgical excision of CHMs remains the treatment of choice [13]. A benign tumor, CHMs, can invade or compress neighboring structures. Larger lesions have associated risks of spontaneous and intraoperative hemorrhage. In our case, the lesion had grown extensively over 3 years, causing severe tracheal stenosis that mandated use of VV-ECMO prior to intubation to safely proceed with surgery. We focus our review of clinical, imaging and pathologic characteristics of CHMs of the mediastinum to highlight for clinicians the importance of considering CHMs in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with a middle mediastinal mass.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

FUNDING

None.