-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Andrei I Gritsiuta, Alexander Bracken, Jorge Lara-Gutierrez, William N Gilleland, Sit-ups and emergency abdominal surgery: a rare case of intestinal volvulus and resultant chylous ascites incited by abdominal exercises, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 4, April 2022, rjac155, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac155

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Chylous ascites is a unique phenomenon defined in the literature by ascitic fluid with a triglyceride content >200 mg/dl. This rather rare entity can be associated with a number of different pathologies related to abnormalities within the lymphatic system. This case report serves to demonstrate an intestinal volvulus and resultant chylous ascites found on exploratory laparotomy in an otherwise healthy individual who participated in routine, extreme abdominal exercises.

INTRODUCTION

Chylous ascites is a relatively rare diagnosis that is becoming increasingly prevalent within the USA, accounting for 1 in 20 000 hospital admissions [1]. A traumatic mechanism has been reported and is attributed to hyperflexion or hyperextension of the spine leading to lymphatic ducts rupture [2]. In addition, intestinal volvulus without evidence of malrotation in adult patients is scantly reported. We herein report an unusual case of intestinal volvulus and resultant chylous ascites incited by exercise, reported in the literature only once previously.

CASE REPORT

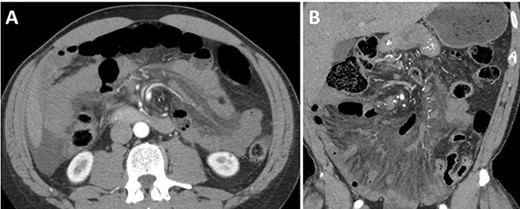

A 44-year-old Caucasian male presented with acute epigastric abdominal pain after strenuous exercise involving hyperextension and flexion (sit-ups) over an exercise ball. He reported two previous similar episodes after exercise that resolved spontaneously, and he had attributed to his new workout routine. His past surgical history was significant only for an umbilical hernia repair 18 months prior to presentation. A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was performed that demonstrated a significantly dilated stomach as well as a proximal loop of small bowel with edema of the mesentery and a whirl sign about the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) axis (Fig. 1). Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed for suspected midgut volvulus. Upon inspection, chylous fluid was found pooling in the mesentery adjacent to erythematous small bowel. The small bowel was carefully run from the ligament of Treitz to the ileocecal valve with no volvulus identified at the time of surgery. No evidence of ischemia or necrosis was identified. No adhesive disease or evidence of congenital malrotation was found. Peritoneal fluid sample was negative for malignancy though demonstrated a triglyceride level of 1451 mg/dl. The postoperative course was unremarkable, and the patient was discharged on postoperative Day 1. Six months later, the patient was admitted again with similar clinical presentation, preceded by abdominal exercises. Abdominal CT scan showed small bowel mesenteric edema and intra-abdominal fluid with a similar whirl sign about the SMA axis as seen in his prior CT scan 6 months earlier. The scan also demonstrated suspected partial superior mesenteric vein (SMV) thrombosis. We proceeded again with diagnostic laparoscopy and chylous ascites was found without obvious etiology. Conversion was then made to laparotomy which similarly failed to demonstrate any cause of the suspected transient intestinal volvulus or the chylous ascites. A confirmatory triple phase CT scan identified the presence of a non-occlusive thrombus of the SMV. He was started on anticoagulation for a 3-month course per hematology recommendations and discharged home uneventfully on postoperative Day 3 with recommendation to avoid any further strenuous exercise.

Abdominal and pelvis CT scan showed diffuse infiltration of the mesentery with twisting of the root of the mesentery, including the superior mesenteric artery and the other arterial branches. Additionally, there is moderate diffuse bowel wall thickening with several nonspecific distended small bowel loops. Diffuse inflammatory stranding throughout the mesentery. (A) Axial and (B) coronal views.

DISCUSSION

Chylous ascites is an extremely rare phenomena defined as the accumulation of milky triglyceride-rich fluid within the peritoneal cavity secondary to the disruption of the lymphatic system by a number of different pathologies [1]. Symptoms related to chylous ascites are frequently not present or nondescript: the two most common symptoms are massive abdominal distention, accounting for 81% of presentations, and nonspecific pain (14%) [3]. These symptoms often have an insidious onset, developing over the course of weeks to months, secondary to their pathologic cause. The suspicion for the presence of chylous ascites is often not made prior to the inadvertent diagnosis, but rather most often made by diagnostic paracentesis or surgical intervention [4]. Diagnosis of pathology in any patient with clinical evidence of ascites is frequently completed at least partially through the use of a diagnostic abdominal paracentesis. In addition to the physical appearance of the chylous fluid, which often takes on a light yellow opaque color, the key in diagnosis is evaluation of the triglyceride level within the fluid. Some sources allow the diagnosis to be made with as little as 110 mg/dl, but most call for 200 mg/dl in addition to other criteria [5]. Once the initial diagnosis is made, it is almost always beneficial to find a source of the chylous leak. This can be achieved through multiple imaging techniques outlined by different resources in the literature: lymphoscinitgraphy is helpful in identifying the drainage patterns of lymph, and lymphangiography not only helps track the flow of lymph, but can be used for invasive management. Laparoscopy and laparotomy also function as a crossover point for both diagnosis and management. Regarding the management of chylous ascites, there are many different techniques represented in the literature, from conservative methods to invasive. Treatment should be individualized and adjusted to the underlying cause. Medical management includes the use of dietary changes and pharmacological interventions as adjuncts. On the conservative end of more invasive management includes palliative abdominal paracenteses as needed. Lymphangiography, as previously discussed, is also a tool that can be used for both diagnosis and management by embolization. Finally, surgical management is warranted when more conservative management fails or the etiology is unknown. Chylous ascites is associated in most cases with malignancies, liver pathologies and infectious diseases. Trauma and iatrogenic injury are well-known causes [1]. Only one case of atraumatic idiopathic chylous ascites after strenuous exercise have been described in the literature [4]. A hypothesis of rupture of the cisterna chyli related to hyperextension and hyperflexion as a possible mechanism has been suggested. Explorative laparoscopy or laparotomy are important adjuncts to radiologic methods to confirm or exclude any underlying cause since the accurate diagnosis and management of underlying disease process can ultimately function to treat the chylous ascites seen secondarily.

Chylous ascites secondary to strenuous abdominal exercise has been demostrated once previously in the literature. The case presented here in a healthy patient without other underlying pathology despite detailed workup supports this previously suggested method of action. Although the connection can be made, the true pathology remains unclear, with speculation as to the disturbance of the cisterna chyli secondary to trauma being the present hypothesis. Further evaluation with the imaging methods described in this report may help prove this hypothesis in the future.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

The research received no specific grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or non-for-profit sectors.

INFORMED CONSENT

Written/verbal informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.