-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Andriy Hordiychuk, Timothy Elston, Traumatic diaphragmatic injury along with ruptured gastrothorax: case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 4, April 2022, rjac154, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac154

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Accidental fall was the 11th leading cause of death in Australia in 2020. It is essential to promptly diagnose traumatic diaphragmatic injury as a complication of thoracoabdominal blunt trauma and make a decision about an urgent surgical intervention, especially if there is a suspected herniation of internal organs into the thoracic cavity. This case report describes the clinical, intraoperative and computed tomography findings of traumatic diaphragmatic injury and ruptured gastrothorax.

INTRODUCTION

Accidental fall was the 11th leading cause of death in Australia in 2020. It is essential to promptly diagnose traumatic diaphragmatic injury as a complication of thoracoabdominal blunt trauma and make a decision about an urgent surgical intervention, especially if there is a suspected herniation of abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity. Diaphragmatic injury with herniation confirmed on computed tomography requires considering a tension gastrothorax as one of the differential diagnoses. The case described below is a clinical course of a patient who sustained blunt trauma to the chest and abdomen due to a fall from height.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 24-year-old male patient was brought in by ambulance to the emergency department after a fall from ~10-m height (a coconut tree). There was a temporary loss of consciousness on the scene, and haematemesis afterwards witnessed by the bystanders. He arrived with a Glasgow coma scale (GCS) of 15, shortness of breath, diaphoretic, blood pressure 97/37 (60/20 on the scene) and heart rate 140 bpm, bilateral chest decompression needles (inserted by ambulance) and no observed movements of lower limbs, haemoglobin level (Hb) of 130 and metabolic acidosis in the venous blood gas results.

The patient has a past medical history of mild asthma and is a fruitarian, with no known surgical history before this trauma accident.

Initially, the patient became agitated in the emergency department required intubation for decreased GCS, a blood transfusion and further insertion of bilateral intercostal catheters. Subsequently, the patient was hemodynamically stabilised and taken for trauma computed tomography (CT).

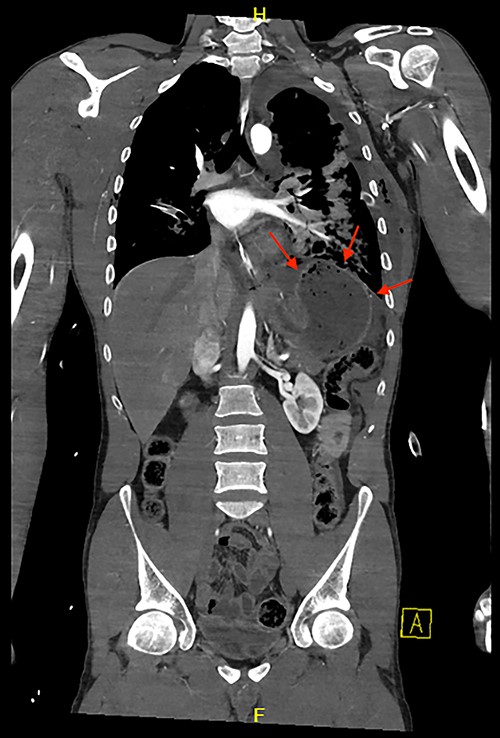

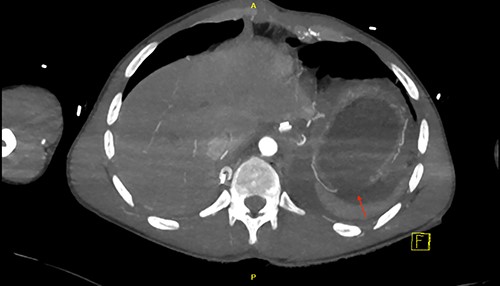

CT scan revealed a large left haemothorax and evidence of left diaphragmatic rupture with herniation of abdominal organs to thoracic cavity such as the spleen, stomach and splenic flexure of the colon; fractured all 12 left ribs, pulmonary contusion, unstable fractures of T6, T10 with acute spinal cord injury (complete transection; Figs 1–3).

Coronal view of CT chest and abdomen with herniation of the stomach and spleen into the thoracic cavity.

Sagittal view of CT scan demonstrates a level of the left hemidiaphragm.

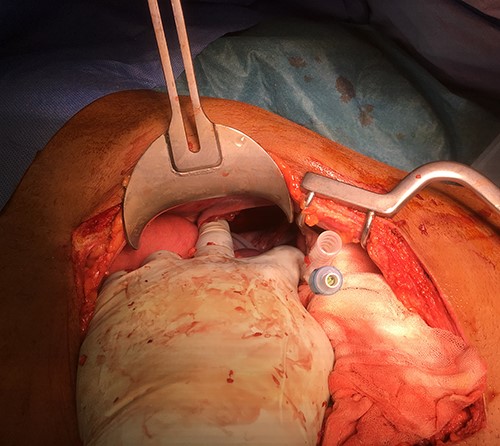

The patient was urgently taken to theatre for exploratory midline trauma laparotomy. Prophylactic antibiotics were administered. During surgery, a 10-cm defect of the left hemidiaphragm (Grade III [1, 2]) and 5-cm full-thickness stomach laceration (Grades II–III [3]) were identified along with contamination of the left hemithorax and abdominal cavity with a stomach content, a significant amount of chewed coconut (Figs 4 and 5).

Intraoperative photo after reduction of the ruptured stomach back to the abdominal cavity.

The spleen was intact. All recognised injuries of the diaphragm and stomach were repaired (0 Nylon for diaphragm and two layers of 3–0 Maxon for stomach) following extensive washout of thoracic and abdominal cavities. After the surgery, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for monitoring. The intraabdominal and intrathoracic drains were removed on the 9th-day post-op.

The patient underwent an orthopaedic intervention for his spinal injury with prolonged admission for rehabilitation afterwards.

DISCUSSION

Traumatic diaphragmatic injury (TDI) is uncommon (<1% in non-penetrating injury [4]), and stomach perforation after blunt abdominal trauma is relatively uncommon (<1.7% [5]). These types of traumas are rare. The combination of those is hard to diagnose. Usually, TDI is combined with pulmonary injury. As described previously, the risk of hollow viscus perforation is higher in the postprandial state.

Diaphragmatic and stomach injuries are associated more with the penetrating mechanism of trauma than blunt trauma, but the mortality rate is higher with blunt trauma [6]. Diagnosis of diaphragmatic or hollow viscus injury is problematic and should be one of the differentials amongst the other more common injuries such as liver, spleen and kidney [7]. Therefore, it is crucial to prioritise further management with combined thoracic and abdominal blunt trauma.

Diagnostic evaluation of trauma patients should be based on ATLS (Advanced Trauma Life Support) protocol together with EAST (Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma) guidelines if possible. In addition to clinical examination, FAST (Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma) scan or mobile plain chest X-ray can easily miss TDI or hollow viscus perforation. CT is more beneficial to detect TDI if the patient is stable enough for imaging—a direct discontinuity of the hemidiaphragm, herniation of abdominal organs, the collar and dependant viscera signs, segmental non-recognition of the diaphragm, focal diaphragmatic thickening, thoracic fluid abutting the abdominal viscera and other indirect signs [8]. In addition, we need to keep in mind the possibility of eventration of the diaphragm that can mimic TDI.

Delayed diagnosis of diaphragmatic injury can lead to potentially life-threatening conditions such as herniation and strangulation of abdominal organs (a tension gastrothorax, for example).

EAST guidelines [9] suggest approaching nonoperatively for the right-sided injuries of the diaphragm and considering an abdominal versus thoracic approach for the left-sided blunt or penetrating TDI. It might decrease mortality, missed abdominal traumatic injury and surgical approach-associated morbidity. Splenic injury has a strong positive association with a left-sided TDI [10], which supports a laparotomy recommendation unless there is a suspicion of pulmonary injury. Diagnostic laparoscopy is recommended for isolated TDI with no concern for other injuries.

Suspected TDI and hollow viscus perforation must be addressed promptly to avoid mortality. CT scan might help with a diagnosis and identify herniation of abdominal organs. There should be no delay in taking the patient with such injuries to theatre to improve the overall outcome.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

Informed signed consent was obtained from the patient before publication.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.