-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Harald Welling, Eirini Tsigka, John Krogh, Volker-Jürgen Schmidt, Michael Munksdorf, Case report: surgical management of massive scrotal lymphedema in a bariatric patient, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 4, April 2022, rjac100, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac100

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A morbidly obese male patient was referred to our department for joint-venture excision surgery of a massive genital lymphedema that had increased 10-fold in volume over a 3-year period. The patient underwent two-stage excision and reconstruction surgery including orchiectomy and was discharged with no major complications and reported improved outcome and urogenital function after surgery at 6-month follow-up. Genital lymphedema is a rare and surgically challenging disease that is related to obesity and causes functional and psychosocial impairment. The planning, performance and postoperative care of surgery on bariatric patients requires tailored surgical treatment and the involvement of several different medical professions and specialties. Surgical debulking can bring about satisfactory outcomes and profound improvements in quality of life.

INTRODUCTION

Genital lymphedema (GL) is a condition resulting from obstruction of the lymphatic drainage of the genital area. GL leads to edema of the interstitial and subcutaneous tissue and subsequently fibrosis, collagenous hyperplasia, loss of elasticity and increased skin thickness [1, 2]. GL most often occurs idiopathically, but it may also occur secondary to other diseases or iatrogenically following lymphadenectomy [2, 3]. The literature on the pathophysiology of GL and the surgical treatment of GL is sparse, but points to obesity as a major contributing cause of GL in the western world [2, 4]. The surgical treatment of GL aims to improve the patient’s mobility as well as urinary and sexual function [1, 3, 5, 6].

CASE REPORT

A 58-year-old morbidly obese male with a body mass index (BMI) of 77 was referred several times to the emergency room due to scrotal pain and increasing swelling (Fig. 1).

Previously, the patient had failed to complete an outpatient weight loss program in preparation for bariatric surgery. More than 3 years after his first visit to the emergency department, the patient was referred to our facility. Physical examination revealed a gigantic mass measuring ~48 × 34 × 46 cm, with the mons pubis and scrotal skin burying the penis in a >40-cm long fistula. The skin was thick and fibrotic with multiple nodules (Fig. 2). The patient had great difficulty walking and managing hygiene, voiding and had lost sexual function of the penis. Hence, a joint-venture surgical approach involving plastic surgeons and urologists was planned with a palliative intent.

Pre-operative evaluation and planning

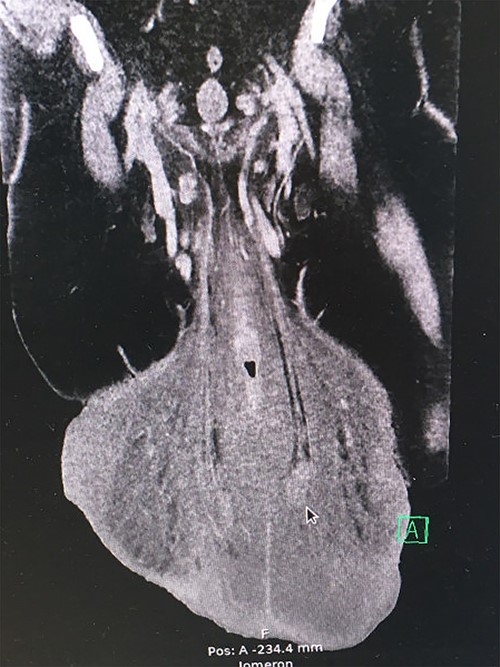

The preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan showed enlarged lymph nodes along the iliac vessels bilaterally and in the groin. Apart from massive edema that had increased more than 10-fold in volume over 2 years, it revealed a network of enlarged veins and intact testicles at the end of a 17-cm long furnicle with no radiological signs of malignancy or herniation (Fig. 3).

Prior to surgery, a bariatric bed and a bariatric ambulance were acquired. The large abdominal pannus led to concern of accessibility of the excision area. Sterile S-hooks from a butcher were used in order to lift the pannus mechanically and ensure proper surgical access (Fig. 4).

Surgical approach

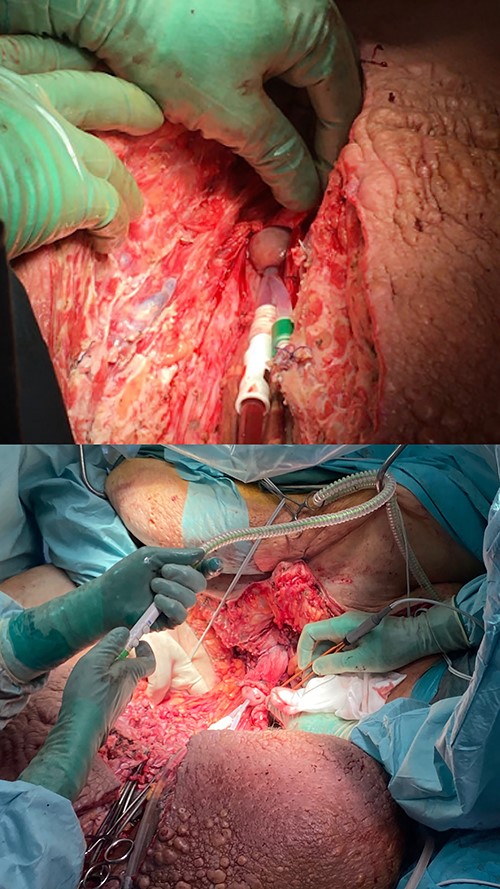

Once the patient was sedated, the urethra was located with a flexible cystoscope and a guidewire was placed. Both the cystoscope and urine catheters were insufficient in length to reach the bladder, and eventually an open-end nasogastric tube was placed.

Excision of the scrotal mass began with a sagittal incision over the urinary catheter through the mons pubis until the glans penis was exposed and secured. Due to the gravitational force of the edematous tissue, the penile skin had been invaginated out over the glans and could not be spared (Fig. 5). During the procedure, several lymphatic cysts were found and numerous dilated vessels ligated. With the assistance of perioperative ultrasound, testis and furnicles were located, but due to the fibrosis of the adherent tissue and the furnicle length, they could not be spared (Fig. 6). Lateral flaps from the primary scrotal area were preserved and brought medially to shape the neoscrotum. The penis remained degloved until later reconstruction with a split-skin graft (Fig. 7).

Sagittal incision of the scrotum until glans penis exposure and handmarking a small portion of the inverted preputium.

Postoperative view after advancement of the lateral scrotal wall to the prepubic incisions lines. The penis remains degloved until secondary reconstruction.

After several hours in the operating room, a combined mass of 26 kg was removed (Fig. 8) and a total amount of 300 separate cloths of gauze weighed in at 14 kg. It resulted in an immediate postoperative weight loss from 255 to 231 kg and a BMI reduction of seven points.

Removed scrotal mass specimen of 26 kg. Frontal and posterior view of the specimen.

Histopathological analysis showed no signs of malignancy and no dysplasia. The patient received testosterone supplementation shortly after surgery and was discharged 23 days post-surgery.

Outcome and follow-up

At 6-month follow-up, there was no recurrence of lymphedema, and the penis was clinically visible and could be reached by the patient (Fig. 9). The patient continued to struggle with commencing weight loss efforts, and for that reason abdominal panniculectomy is not planned yet.

DISCUSSION

GL is a chronic disease with a multifactorial pathogenesis often involving obesity and diabetes [2, 3, 7]. Due to the increased rate of complications in obese and post-bariatric patients and the severity of complications related to excision surgery, patients are rarely offered surgical treatment at initial consultation [3]. Potentially, this may lead to delay in treatment or the prevention of disease progression. In selecting the right surgical approach for the patient, it is important to address the extent of the issue, the state of disease progression and any contributing pathology.

Lymphatic anastomosis can be sought out in GL patients in the very early stages with satisfying results and low reported risk of recurrence: successful results are reported in so-called physiologic surgery aiming to improve anterograde flow of lymphatic fluid by increasing the drainage capacity or ultramicrosurgical lymphatico-venous anastomosis [8–10].

Several different ways to reconstruct the area after excision have been described: local lateral laps from the primary scrotal area were used in our case because the patient had sufficient amount of unaffected skin in the perineal area [6, 11]. Preserving the testicles presents a challenge if the degree of fibrosis is extensive or if the furnicle has been stretched to an extreme degree. However, ablative surgeries in GL are described to preserve vital and functional testicles despite the debulking of the big mass and to increase quality of life [3, 6, 11, 12]. In the present case, testicle length could not allow survival if preserved, unless microsurgical reanastomosis was performed.

GL with buried penis syndrome in a morbidly obese patient is a challenging case regardless of patient compliance. Ablative joint-venture surgery with tissue excision and reconstruction can provide satisfactory outcomes and profound improvements in quality of life. Surgery on morbidly obese patients warrants long-term planning and coordination. Further studies are warranted to investigate long-term outcomes for larger genital area excision surgery.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

References

Author notes

Harald Welling and Eirini Tsigka have shared first authorship in the article.