-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kelvin Adasonla, Sandeep Pathak, Chi-Ying Li, Large, infected Cowper’s syringoceles: a rare cause of perineal sepsis in adult men, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 12, December 2022, rjac568, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac568

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Urologists and general surgeons alike are familiar with assessing acute perineal pathology. A Cowper’s gland syringocele is a rare cystic dilatation of the male bulbourethral gland, typically seen in children. We report the diagnosis and emergency management of two adult cases of large, infected Cowper’s gland syringoceles. A comorbid 76-year old was diagnosed with sepsis and penile swelling, but there was no discrete superficial pathology. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a perineal collection communicating with the membranous urethra. A suprapubic catheter was inserted, and aspiration was attempted. Meanwhile, a 55-year-old diabetic presented with severe perineal pain. MRI revealed a deep perineal collection, involving the scrotum and proximal penis. He improved with antibiotics and aspiration of the collection. This rare diagnosis may be more common in older men than previously thought. Pelvic MRI is a key diagnostic tool. A minimally invasive approach is possible in those with considerable perioperative risk.

INTRODUCTION

Cowper’s glands, also known as bulbourethral glands, are accessory glands located in the urogenital diaphragm that drain into the bulbar urethra. They are analogous to Bartholin’s glands in females. Their secretions lubricate the urethra and neutralize any residual acidic urine prior to ejaculation [1]. A syringocele is dilatation of the main duct of Cowper’s gland.

Cowper’s syringoceles are typically diagnosed in the paediatric outpatient population and associated with voiding lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). We report the diagnosis and emergency percutaneous drainage of large Cowper’s syringoceles that developed into abscesses.

CASE 1

A 76-year-old male was admitted delirious and pyrexial. He had a background of severe dementia, recurrent urinary tract infection (UTIs) and was dependent on carers for activities of daily living. White cell count was 53 × 109 with a profound neutrophilia, and a C-reactive protein (CRP) of 73 mg/L. He was commenced on broad spectrum antibiotics, and blood cultures grew a Streptococcus anginosus bacteraemia. He was found to have a grossly swollen penis along its ventral surface, with tenderness on palpation but no skin changes or fluctuance of the penis, scrotum or perineum. Digital rectal examination revealed a smooth, non-tender prostate. Examination and baseline investigations did not reveal a clear source of sepsis from other sites. Mid-stream urine sample, sent after commencing antibiotics, was negative.

Ultrasound penis showed marked soft tissue oedema of the penile shaft and glans, but no discrete collection and normal corpora cavernosa and urethra. A urethral catheter was inserted as part of sepsis management, and due to voiding difficulties from the swelling. There was no significant residual volume. A CT abdomen and pelvis was requested to identify a potential underlying cause of the penile swelling. This demonstrated a collection around the prostate, membranous urethra and rectum, with no other abdominopelvic pathology. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed a 3 × 3 cm collection inferior to the prostate, and posterior to and communicating with the membranous urethra, but no prostatic abscess.

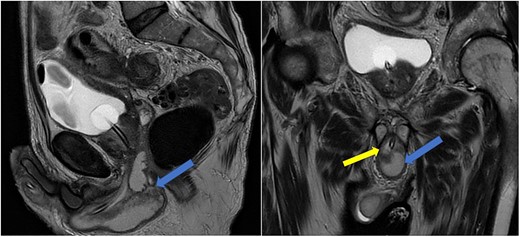

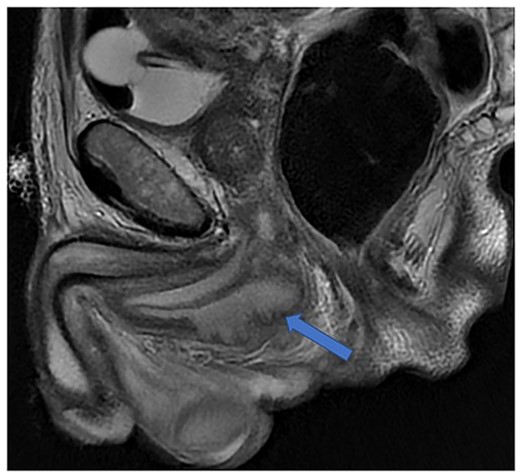

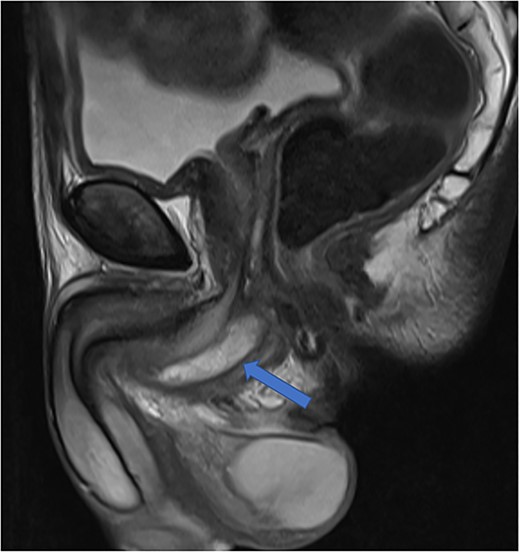

Imaging was suggestive of an infected Cowper’s syringocele. As the patient was clinically stable, a trial of antibiotic therapy was suggested. Repeat MRI a week later showed that the collection had extended into the corpus spongiosum, which now appeared expanded with the fluid density signal (Fig. 1). On a review, the urethral catheter was thought to be impairing potential drainage of the collection. It was removed, and a suprapubic catheter was inserted. Ultrasound guided aspiration failed to drain a significant amount of pus, which also grew S. anginosus. There was also radiological suspicion of a colovesical fistula. The patient was reviewed by the colorectal surgeons, who felt that as there were no other symptoms relating to the fistula, and the patient was physiologically frail, and defunctioning of the bowel would be inappropriate. Likewise, the patient was deemed too frail for any surgical management of the collection. He was discharged after a total of 6 weeks’ antibiotics. Repeat MRI 4 months later (Fig. 2) showed a smaller but persistent collection.

Case 1: sagittal and coronal T2-weighted images showing the collection (blue arrow) inferior to the prostate, and involving the corpus spongiosum (yellow arrow).

Case 1: T2-weighted axial image 4 months later, showing slight reduction in the size of the collection (arrow).

In view of his significant comorbidities and the absence of any clinical signs or symptoms, he is being managed conservatively with a long-term suprapubic catheter.

CASE 2

A 55-year-old male presented with a 1-week history of perineal pain. He had a background of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, chronic pancreatitis, a 30-pack-year smoking history and was awaiting colonoscopy for a change in the bowel habit. This pain radiated to his anus and left testicle. He had some associated dysuria. He had nocturia three times a night for several years. He denied any voiding LUTS, fever or rigours.

On examination, his external genitalia had no abnormalities, but there was tenderness to palpation in the perineum. However, there were no skin changes or fluctuance. Digital rectal examination revealed a smooth, non-tender prostate. There were no obvious perianal abnormalities, blood or purulent material revealed per rectum. He was apyrexial, and urine dipstick analysis was negative for leucocytes, blood and nitrites. Initial blood results revealed a normal white cell count of 5.3 × 109 and an elevated CRP of 190 mg/L.

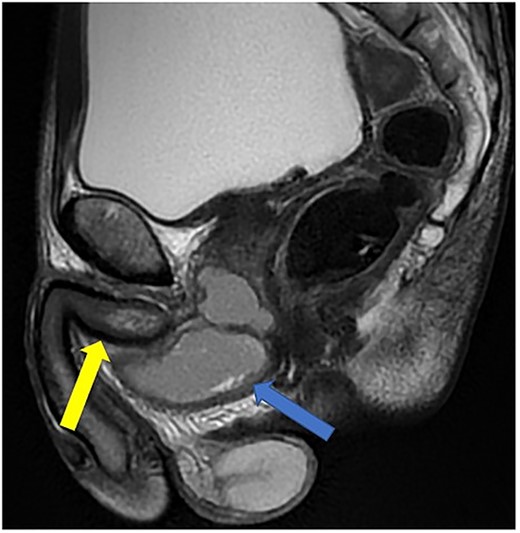

He was put on an empirical course of ciprofloxacin to treat a presumed complicated UTI, and a pelvic MRI was requested. Urine culture grew an Enterobacter cloacae organism. The MRI scan revealed a 7 × 3 cm perineal collection inferior to the prostate and adjacent to the membranous urethra, with increased wall enhancement and fluid with restricted diffusion, with a diagnosis of Cowper’s syringocele (Fig. 3).

Case 2: T2-weighted sagittal MRI image demonstrating a complex, cystic perineal collection (blue arrow), seen in relation to one of the corpus cavernosa (yellow arrow).

The patient was reviewed again a week later. On examination, a tender perineal mass extending into his posterior scrotum had developed. Again, there were no perianal skin abnormalities on examination. He was put on intravenous antibiotics, and a repeat MRI of his pelvis was organized. This revealed a persistent perineal collection, in proximity with, but not involving, the external anal sphincter, as well as the bulbar urethra and scrotum (Fig. 4).

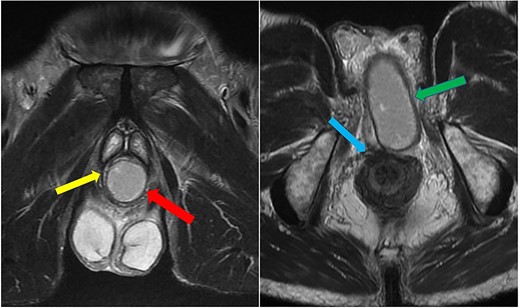

Case 2: coronal and axial T2-weighted images demonstrating the collection (red and green arrows) significantly compressing the urethra and corpus spongiosum (yellow arrow) to the right of the midline, and close to, but not involving, the anal sphincter (blue arrow).

The diagnosis of an infected Cowper’s syringocele was made. The patient underwent ultrasound guided transperineal aspiration of the collection with an 8Fr needle, which drained 40 ml of the purulent material. There was no growth on the pus culture. He clinically improved, with significantly reduced swelling of the perineum and scrotum, and was discharged 48 h later, on oral antibiotics. Post-aspiration uroflowmetry determined a maximum flow rate of 20.8 ml/s. The patient was taught clean intermittent self-catheterisation due to post-void residuals of 300 ml. The patient’s perineal pain had much improved. Repeat MRI at 4 weeks showed a reduced but persistent perineal collection (Fig. 5). He is awaiting specialist review regarding potential further treatment in view of the residual collection.

Case 2: T2-weighted sagittal image showing a reduced perineal collection post-aspiration.

DISCUSSION

A Cowper’s gland syringocele is uncommon, and typically diagnosed in the paediatric and adolescent population [2]. They have been classified according to fluoroscopic appearance [3], communication with urethra [4] and presence of urinary obstruction [5]. However, these classifications are either radiological, or primarily relate to urinary symptoms. It is unusual for this condition to be diagnosed in the middle age, but it is suspected to be more common than previously thought [6]. Its presentation in this population varies, from incidental findings during evaluation of urethral stricture, to dysuria and voiding LUTS [6]. Acute presentations of a painful mass with superimposed infection have been reported [6, 7].

Diagnosis of a Cowper’s syringocele is dictated by clinical presentation. Patients diagnosed with voiding LUTS are investigated with uroflowmetry, those with suspected urethral stricture are further investigated with urethrography and voiding cystourethrography (VCUG), the latter two of which may demonstrate communication between the ducts and urethra [8].

These diagnostic tools were less relevant in our case, where the presenting complaint was acute perineal pain and swelling. Therefore, a wider list of differential diagnoses, including non-urological pathology, was considered. One of our patients had uroflowmetry post-aspiration, which demonstrated a satisfactory maximum flow rate, and so additional lower urinary tract investigations were not requested.

MRI of the pelvis was key to reaching a diagnosis in our experience. It is a non-invasive, readily available and reproducible investigation that accurately defined the anatomy of the pathology. Its use was necessary as there was no evidence of superficial perineo-scrotal abscess in either case. The wall enhancement and restricted diffusion on T2-weighted images suggested an acute inflammatory process. The close proximity of the mass to the external anal sphincter likely contributed to the patient’s anorectal symptoms. Contemporary use of pelvic MRI has led to incidental findings of Cowper’s syringocele [9], and it has aided in the diagnosis of other large syringoceles presenting acutely [7, 10]. Penile and perineal ultrasound has also been used in this context [11].

The exact aetiology of Cowper’s syringocele remains unclear [2, 12]. Bevers et al. described them as ‘closed’ if the syringocele lacks communication with the urethra, thereby prone to becoming periurethral mass [4]. It has been suggested that ‘closed’ Cowper’s syringoceles develop progressive duct and gland dilatation due to increased intraluminal pressures within the duct and gland [4, 6]. Moreover, there is thought to be an association with stricture of the bulbar urethra [6]. Neither of our cases was specifically investigated for the urethral stricture, but there was no background of previous stricture, significant voiding LUTS or difficult urethral catheterization. Although there was no growth in the pus culture following drainage in the second case, this patient had a recent E. cloacae UTI, and there was no evidence of skin or perianal involvement with the abscess. Similarly, in Case 1, S.anginosus was isolated in both blood and pus aspirate culture. This organism, part of the commensal flora of the gastrointestinal tract, has been implicated in abscess formation [13]. This suggests residual communication of the syringocele with the urinary tract as a source of infection.

Smaller, asymptomatic syringoceles are often managed conservatively [12], whereas those compressing the urethra have been managed with transurethral deroofing or marsupialization [4]. Large, infected syringoceles have previously required transperineal excision [6, 7, 10]. This approach was considered in this case. However, there were significant concerns regarding perioperative morbidity in both cases, especially Case 1. Case 1 had significant cognitive impairment and was heavily dependent on others for activities of daily living. Case 2, meanwhile, was a heavy smoker and a poorly controlled diabetic, with a haemoglobin A1c level of 105 mmol/mol.

Management of this condition is challenging. The approach of defunctioning the urethra and percutaneous aspiration has been attempted elsewhere to good effect [14], but has not prevented a recurrence in other cases [15, 16]. However, surgical management would require a large perineal incision and potentially urethral repair if involved. This has implications of delayed wound healing, persistent infection and has been associated with urethral fistulation [15, 16]. In both cases, the patients remained clinically stable, and there was considerable multidisciplinary discussion and consultation with the patient and next of kin. It was felt that percutaneous aspiration, extended antimicrobial therapy and optimization of medical conditions was preferrable to open surgery. Close follow-up, interval imaging and specialist referral for excision of any significant residual mass are essential following non-operative management.

CONCLUSION

The true incidence of Cowper’s syringoceles in adults may be higher than previously thought. However, large, infected Cowper’s syringoceles are a rare phenomenon. MRI was key to diagnosis and should be employed early when faced with perineal pathology without an obvious superficial cause. Percutaneous aspiration, in conjunction with extended antimicrobial therapy, is a viable management strategy when concerned about significant perioperative morbidity.

References

- antibiotics

- magnetic resonance imaging

- sepsis

- diabetes mellitus

- surgical procedures, minimally invasive

- edema

- perioperative cardiovascular risk

- adult

- bulbourethral gland

- child

- comorbidity

- cysts

- dilatation, pathologic

- emergency treatment

- anogenital region

- diagnosis

- pathology

- penis

- scrotum

- cystostomy, suprapubic

- clinical diagnostic instrument

- older adult

- membranous urethra

- perineal pain

- magnetic resonance imaging of pelvis

- urologists