-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Austin C Kassels, Joshua Melamed, Austin Rogers, David Johnstone, Thoracic chordoma in a 36-year-old female, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 12, December 2022, rjac541, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac541

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Chordomas are rare tumors that occur in the bones of the skull base and spine, affecting 1 in 1 000 000 people per year. Thoracic chordomas comprise just 1% of chordomas. A 36-year-old female underwent a right video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical resection for a cystic mass at the level of T2-3 which was well-circumscribed. Despite efforts to achieve an intact resection, there was tumor spillage due to friability, and it was taken off the bony vertebral body with no margin. The final pathologic diagnosis was chordoma. Thoracic chordomas are rare, slow-growing, recurring neoplasms that require proper preoperative diagnostic imaging and ideally preoperative trocar computed tomography-guided biopsy from a posterior approach if anatomic access is possible. They are prone to dissemination and sarcomatous differentiation. The surgical approaches for reported thoracic chordoma tumors vary due to their rarity and the variation in tumor location and presentation.

INTRODUCTION

A chordoma is a bone tumor that displays notochordal differentiation from the persistent notochordal elements of embryonic development [1]. Chordomas are rare tumors that occur in the bones of the skull base and spine, affecting 1 in 1 000 000 people per year [2, 3]. They present in the sacrum, skull base or mobile spine, with a prevalence of 50, 30 and 20%, respectively [1]. Thoracic chordomas comprise just 1% of chordomas [4–6]. Negative prognostic factors include larger tumor size, positive surgical margins, microscopic tumor necrosis, Ki-67 > 5% and local recurrence [7]. Data have shown that the only factor associated with a disease-free state for >5 years is margin-free en bloc resection [5].

CASE REPORT

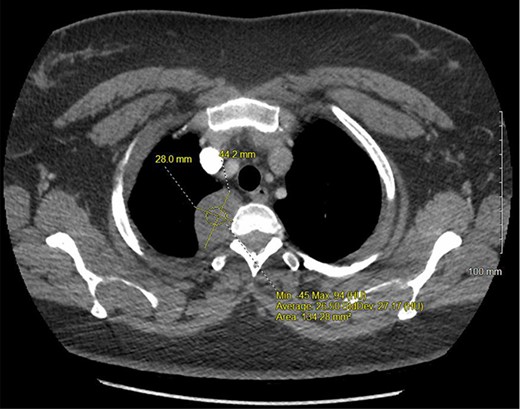

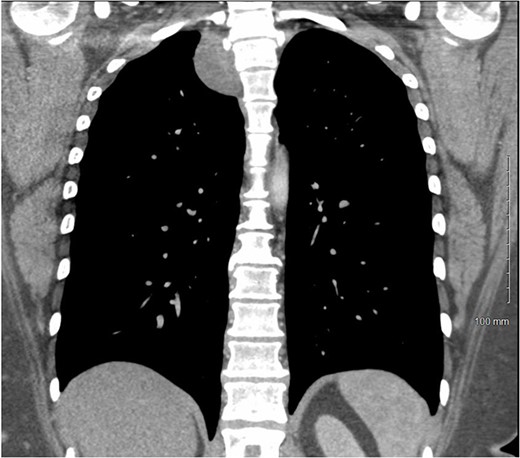

A 36-year-old female presented to an outside emergency department reporting chest pain, dizziness and abdominal pain for 7 hours. A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the chest revealed a right paraspinal 4.2 × 2.8 × 3.3-cm cystic mass at the level of T2-3, which was well-circumscribed (Figs 1 and 2).

CT chest with IV contrast transverse view with detailed measurements of right T2-T3 paravertebral mass.

CT chest with IV contrast coronal view of right T2-T3 paravertebral mass.

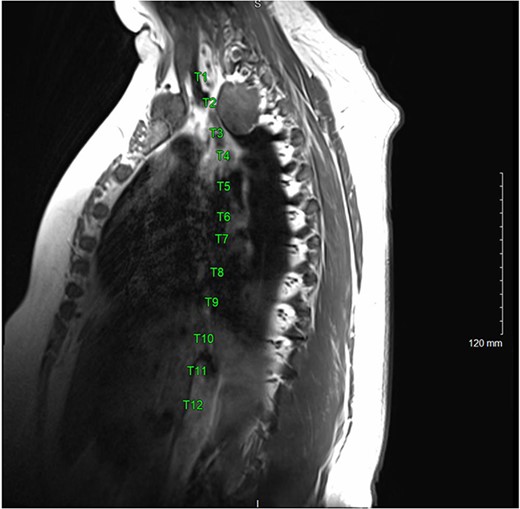

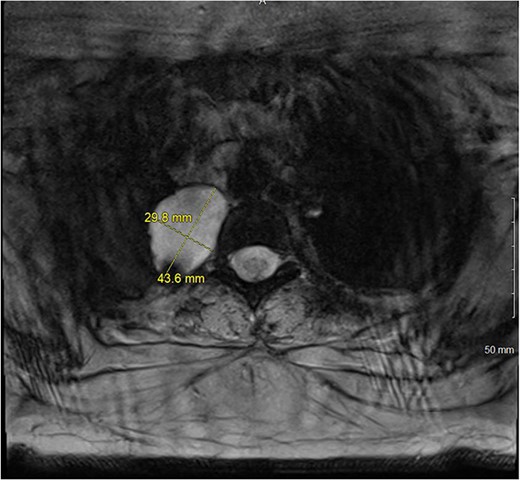

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that the tumor extended into the outer aspect of the right T2-T3 neural foramen and could represent a nerve sheath tumor. Sixteen months later, neurosurgical consultation repeated her MRI, which showed that the mass had grown 2 mm (Figs 3 and 4). There was no extension into the neural foramen or bone erosion.

The patient underwent a right video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical resection. The mass was found to be gelatinous, not well-encapsulated and intimately involved with the sympathetic chain at the level of the first rib. Despite efforts to achieve an intact resection, there was tumor spillage due to friability, and it was taken off the bony vertebral body with no margin. The patient was discharged with a minor Horner’s syndrome which eventually resolved. The final pathologic diagnosis was chordoma. After multidisciplinary review, the patient was referred for proton beam therapy and received intensity-modulated radiation therapy to the tumor bed and then was referred for consideration of additional proton therapy.

DISCUSSION

Thoracic chordomas are rare, slow-growing and recurring neoplasms that are prone to dissemination and sarcomatous differentiation [8]. Two publications, from 2012 and 2016, note finding ~30 reports since 1902 of thoracic spine chordomas [4, 9]. With regard to chordomas overall, most occur in middle age with a peak during the sixth decade of life [4–7]. Thoracic spine chordomas, however, present earlier with mean age at presentation of 35.7 years [4]. It is important to consider prognostic factors, such as age, sex, treatment history, tumor location, pathological grade, surgical margin, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, while determining long-term prognosis and considering treatment plans [10]. There is no effective systemic treatment of chordomas, and radiotherapy is combined with surgery to improve local control [10].

The surgical approaches for reported thoracic chordoma tumors vary due to their rarity and the variation in tumor location and presentation [4]. If possible, en bloc resection followed by proton beam therapy can be utilized as a treatment method to yield the longest disease-free period and highest rate of overall survival [4–6]. A major advantage of proton beam therapy over standard radiation therapy is that protons deposit the majority of their radiation dose directly in the tumor and do not travel further through the body. As a result, healthy tissues and organs receive less radiation [11].

The 5-year survival after surgical resection and radiation of spine chordomas vary between 50 and 60% [4–6]. The 10-year survival rate for chordomas is 40%, and the median overall survival for patients with these tumors is 7 years [12]. The Chordoma Consensus Group has classified surgical margins: wide resection with at least 1-mm margin, marginal resection with <1 mm around the tumor and intralesional resection with visible tumor left behind or tumor cells spilled into the surrounding area [13]. In this case, an intralesional resection occurred [5, 7].

Ideally, a preoperative tissue diagnosis would have been useful in this case. The preoperative findings were not specific. The preoperative presentation (constant, moderate and non-positional pain anteriorly in the right first and second intercostal area), while characteristic of a chordoma, may also be caused by other neurogenic lesions which are more common [14]. For spine tumors, a trocar CT-guided biopsy is recommended and should be done from a posterior approach [14]. Additionally, tissue samples should be evaluated for the presence of brachyury, which is expressed in high levels in chordomas [15]. A high index of suspicion would be required to pursue such workup, as these tumors often lack specific symptoms and present with non-specific findings on imaging [12].

Thoracic chordoma tumors are very rare tumors that require proper preoperative diagnostic imaging and ideally preoperative trocar CT-guided biopsy if anatomic access is possible. Non-specific symptoms and imaging characteristics, however, pose difficulties while developing differential diagnoses for cases involving thoracic chordomas because such a diagnosis is extremely rare. Ideally, chordomas should undergo margin-free en bloc resection to minimize recurrence. A combination of preoperative diagnostic results and intraoperative strategy should direct the excision of unknown thoracic tumors to be resected in the safest way possible to ensure complete resection and to prevent seeding during resection.

AVAILABILITY OF MATERIALS AND DATA

As this paper is a case report, all data generated or analyzed are included in this article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors wrote, read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

The listed authors have not received funding for this manuscript.