-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sean Dolan, Anton Alatsatianos, Kerrie McAllister, Thushitha Kunanandam, Concurrent subglottic and carotid sheath haemangiomas in a paediatric patient – an extremely rare clinical entity, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 11, November 2022, rjac542, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac542

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Multiple haemangiomas of the head and neck area have been reported sporadically in the literature. Concurrent subglottic and carotid sheath haemangiomas have not been reported before in the paediatric population. The authors present the case of a 13-week-old child admitted under the paediatric ENT team with stridor. Diagnostic micro-laryngoscopy identified a subglottic haemangioma as the cause of stridor and subsequent magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated an incidental 7 cm carotid sheath lesion extending from the skull base to the superior mediastinum. Subsequent biopsy confirmed a benign infantile haemangioma. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of concurrent subglottic and carotid sheath infantile haemangiomas in a paediatric patient. Here we discuss the clinical features and management of infantile haemangioma.

INTRODUCTION

Infantile haemangiomas (IH) are the most common benign vascular tumours of infancy [1]. There is a reported incidence of 4–5% in white infants (lower in African/Asian infants) of which 60% affect the head and neck region [1].

Concurrent subglottic and carotid sheath haemangiomas are extremely rare in the paediatric population with no cases reported in the literature. The authors would like to report a case of concurrent subglottic and carotid sheath haemangiomas in a 13-week-old child.

CASE REPORT

Presentation

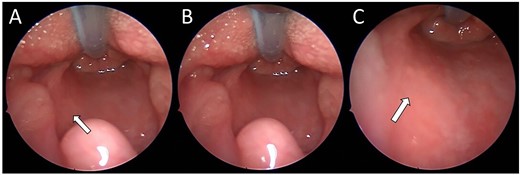

A 13-week-old child was acutely referred to the tertiary paediatric ENT team with stridor. The child had altered breathing for 2 weeks, initially treated as croup. On admission, the child had a tracheal tug, intercostal recessions and significant stridor. A 10 cm facial cutaneous plaque haemangioma was noted. Intravenous dexamethasone was commenced and micro-laryngoscopy showed a subglottic haemangioma occupying 40% of the airway, equivalent to Myer-Cotton classification Grade 1 (Fig. 1). Oral propranolol was commenced at 1 mg/kg/day in three divided doses as per local protocol increasing to 2 mg/kg/day once treatment was established. No neck lesion was apparent on clinical examination.

(A) Endoscopic (MLB) photographs of the supraglottic region. (B–C) Endoscopic (MLB) photographs of glottic and subglottic regions highlighting the presence of a subglottic haemangioma.

Investigations

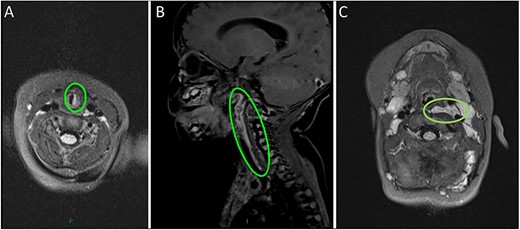

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) head/neck took place due to the presence of a facial plaque haemangioma (increased risk of PHACE syndrome) revealing an incidental lobulated lesion within the deep soft tissues of the left neck, measuring 2.7 × 7.4 cm with hyper-intense signal from the left carotid sheath (Fig. 2). The lesion extended from the skull base superiorly to the mediastinum inferiorly involving the left carotid space. The lesion extended between the internal and external carotid arteries. There was associated mass effect with effacement of the left pharyngeal mucosal space and left posterior oropharynx.

(A) MRI scan highlighting the subglottic infantile haemangioma. (B–C) Sagittal and axial MRI images of the carotid sheath haemangioma.

The patient was discussed at the ENT paediatric radiology meeting and an interval MRI was recommended.

Repeat MRI at 3 months showed a persistent complex lesion involving the left carotid space with unchanged signal characteristics centred at the carotid bifurcation. The urinary sample for catecholamines was negative.

Surgery

On review of the imaging, the child underwent a biopsy of the lesion for a tissue diagnosis. Direct inspection revealed bulging of tissue from the left parapharyngeal space (Fig. 3). The mucosa was incised, constrictor muscles were divided and incisional biopsies were obtained. Histopathology samples showed lobules of haemangioma, strongly positive for GLUT-1 on immunohistochemistry confirming a carotid sheath infantile haemangioma. The patient continues to be followed up in the outpatient setting.

(A–C) Intra-operative endoscopic photographs highlighting the left sided asymmetric parapharyngeal fullness immediately inferior to the inferior pole of the left tonsil where the biopsy was undertaken and macroscopically abnormal tissue identified.

DISCUSSION

Subglottic haemangiomas have been widely documented in the paediatric ENT literature, and carotid sheath haemangiomas have been described in the adult population. There are no cases of concurrent subglottic and carotid sheath haemangiomas in the paediatric population, to our knowledge, with no cases reported of carotid sheath IH.

Literature review

A literature search of Cochrane Library, Embase, Medline and PubMed found four case reports detailing carotid sheath haemangiomas in the adult population (age range 51–87). A case report in 2014 discussed a 9-year-old girl who developed an epithelioid haemangioma of the internal carotid artery after several cannulations of the ipsilateral internal jugular vein for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as an infant [2]. The authors suspected the development of the haemangioma was related to the traumatic effect of repeat cannulation of the internal jugular vein [2]. A 1963 Japanese case report detailed a 16-year-old patient who was diagnosed with a neck mass and subsequently found to have a mass at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery that was diagnosed as a non-specific haemangioma on post-operative angiography [3].

Vascular lesion classification

Vascular lesions are broadly divided into vascular tumours and vascular malformations based on the modified International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies classification [4]. Haemangiomas are benign thin-walled blood vessel tumours and the most common soft tissue tumour in infants and childhood [4].

IH usually occur within the first 8 weeks of life in comparison to congenital haemangiomas that are rarer and present from birth, with limited growth thereafter [4]. IH exhibit a classical period of growth to a spontaneous involution phase usually by 5 months of age [4]. 80% of the absolute growth is completed by 3 months followed by growth stabilization and regression with 90% undergoing complete regression by 4 years of age [5]. IH occur in 4.5% of mature neonates and have a higher incidence in female, premature, low birthweight babies [4].

Clinical appearance of infantile cutaneous haemangiomas depends on the distribution and depth [6]. IH can be classified as superficial, mixed or deep based on their depth and focal/solitary, multifocal and segmental based on the involvement or morphological pattern [6]. Focal/solitary lesions are the most common accounting for 80% of all IH [1, 7].

Subglottic haemangiomas account for 1.5% of congenital laryngeal abnormalities [8]. They present in a paediatric population with biphasic stridor (usually a few months after birth) or as suspected recurrent episodes of croup [8]. Children with cutaneous haemangiomas have a 0.5% risk of having a concurrent subglottic haemangioma and these usually occur in the segmental subtype [7]. Cutaneous IH in the ‘beard’ region (chin and anterior neck) in a child with respiratory distress may indicate the presence of a subglottic haemangioma.

Management of infantile haemangioma

Medical management of IH usually occurs in complicated haemangiomas including ulcerated lesions, anatomical locations likely to cause impairment, syndromic haemangiomas or lesions that will cause disfigurement [9].

Propranolol is a mainstay in the management of IH after being first described in 2008 and acts via a postulated mechanism of inhibition of angiogenesis [9–11].

Rebound regrowth of haemangiomas can occur after propranolol cessation, which is estimated to occur in 19–25% of cases [9]. 0.9% of IH display resistance to propranolol, as in our case [10].

Surgical excision and laser treatment modalities were previously used for the management of certain haemangiomas but are now only used in propranolol unresponsive IH in life-threatening cases [8].

GLUT-1, which was strongly positive in our patient’s histopathology specimen, is an erythrocyte-type glucose transporter that is expressed in the endothelium of blood-tissue barriers [11]. GLUT-1 is strongly positive in IH but negative in other vascular malformations and tumours [12].

Concurrent subglottic and carotid sheath IH remains a very rare condition with no previous paediatric cases reported. This highlights the difficulty in diagnosing paediatric vascular lesions especially if there is no response to propranolol.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT

S.D. (Principal Author), A.A., K.M.A., T.K. agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.