-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Victoria Cook, Animesh A Singla, David Herlihy, Juanita Chui, Charles Fisher, Vikram Puttaswamy, Involvement of Kommerell’s diverticulae—a new anatomical risk factor for acute aortic syndrome progression and technical considerations, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 10, October 2022, rjac489, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac489

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present two cases of acute aortic syndromes (AAS), involving an aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA) with associated Kommerell’s diverticulae (KD). One of the cases involves a penetrating aortic ulcer in patients with an ARSA and KD and represents the first reported such case in the literature. Both cases progressed despite optimal medical therapy suggesting AAS with this anomalous anatomy needs a more aggressive operative approach. The involvement of KD in a patient with AAS appears to increase aortic disease progression and this anatomical variation should be considered another anatomical criterion that may place these patients at higher risk of complication. Progression during conservative management and waiting for the patient to be in the traditional safer ‘sub-acute’ time frame after presentation increased the eventual difficulty of the hybrid repair. A hybrid open-endovascular repair was utilized in all cases and is a safe and effective strategy for managing patients with ARSA and KD presenting with AAS.

INTRODUCTION

Type B aortic dissection has become one of the most prevalent aortic emergencies in the 21st century. It has overtaken emergency aortic aneurysm rupture repair due since the advent of endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) and rapid uptake of elective EVAR surgery worldwide. While in Type A aortic dissection, surgical repair is still regarded as mainstay of treatment. For uncomplicated Type B dissection (TBAD), a recent paradigm shift in treatment has occurred. This has largely focused on treatment in the ‘sub-acute’ phase for those uncomplicated dissections deemed to have ‘high risk’ for negative aortic remodeling. The role of any aberrant aortic arch anatomy in aortic dissection is less well defined. In particular, the role of an aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA) with Kommerell’s diverticulum (KD) involved in dissection is unclear. This paper aims to explore a case series of consecutive TBAD with concurrent ARSA/KD.

CASE 1

An 81-year-old female of Cantonese descent presented to the emergency department after being woken from sleep by a band-like upper abdominal pain radiating to the back. Her past medical history was significant for well-controlled hypertension and hypercholesterolemia.

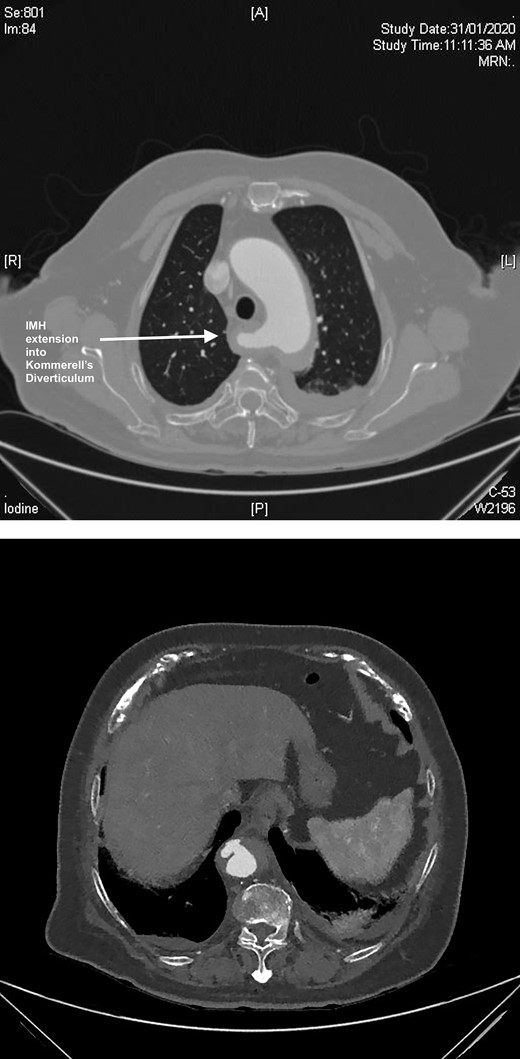

A computed tomography (CT) angiography was performed identifying a penetrating aortic ulcer (PAU) at the level of T11 with an intramural hematoma (IMH) extending to the inferior origin of the left subclavian artery origin (Fig. 1A). The IMH extended into ARSA with an associated KD (Fig. 1B). She was transferred immediately to the intensive care unit for anti-impulse therapy (dP/dt). The patient’s pain initially settled but then recurred during the admission and was refractory to blood pressure control.

(A) CT axial slice demonstrating PAU. (B) CT axial slice IMH seen extending into the KD.

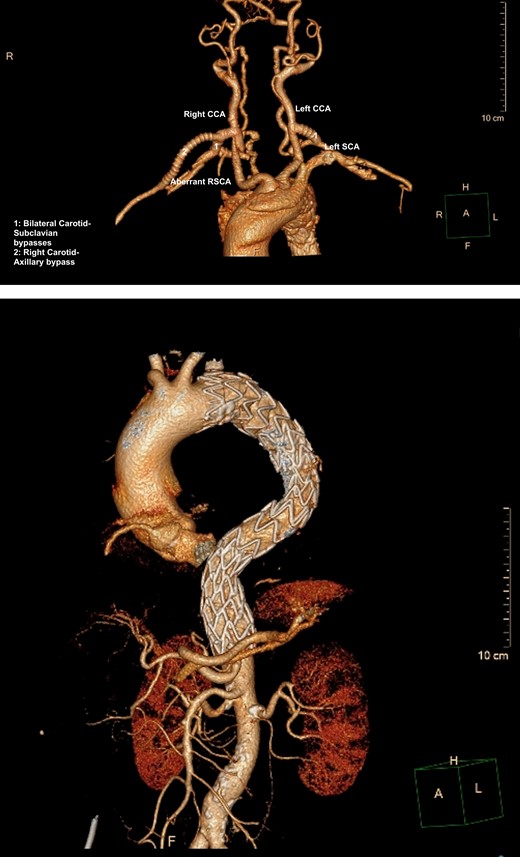

A semi-urgent endovascular thoracic aorta repair (TEVAR, Navion, Medtronic) was performed, with bilateral carotid–subclavian (C-S) bypasses. Intraoperatively, the IMH was noted have progressed to involve the usual mid-segment of the subclavian artery. As a result, a further bypass onto axillary artery was required. She made an uneventful recovery with follow-up imaging at 7 days and 1 month postoperatively showing slow resolution of her IMH and patent bypass grafts (Fig. 2A, B).

(A) 3D-CT reconstruction of extra-anatomical debranching of supra-aortic vessels with bilateral C-S bypasses. (B) 3D-CT reconstruction of thoracic endovascular repair.

CASE 2

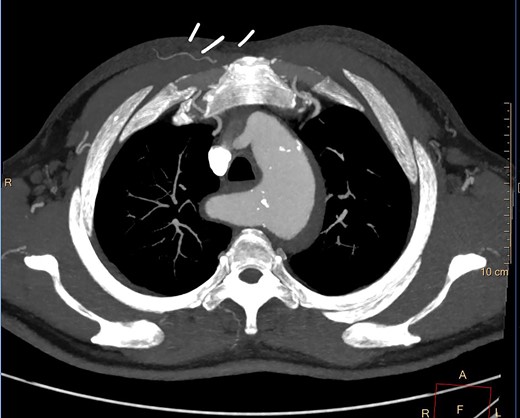

A 61-year-old male presented to a peripheral hospital emergency department with a 12-hour history of central chest pain with onset during sexual activity. He was an active smoker with poorly controlled essential hypertension. CT angiography showed an IMH from the left common carotid artery origin to the distal descending thoracic aorta, also involving the proximal ARSA and KD (Fig. 3).

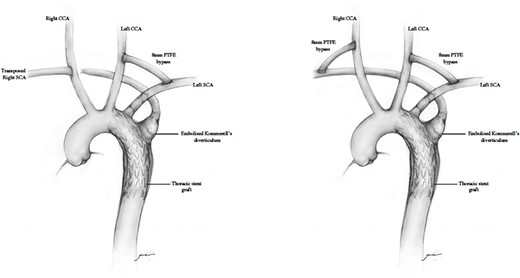

Despite optimal anti-impulse therapy, the patient had refractory chest/upper back pain. The patient underwent a left C-S bypass and right subclavian to common carotid artery transposition (with oversewing of proximal subclavian stump). This was followed by deployment of covered thoracic endovascular graft (Navion, Medtronic) from left common carotid artery (CCA) to 5 cm proximal to celiac artery proximally. The left subclavian artery was occluded using endovascular plugs. His postoperative 2-week CT showed good stent apposition and no endoleak (Fig. 4A, B). He was discharged Day 14 and returned to regular work at 1-month time interval.

(A) 3D-CT reconstruction showing post op repair and Right subclavian to carotid transposition. (B) 3D-CT reconstruction showing post op repair and left C-S bypass.

DISCUSSION

Aberrant anatomy—arteria lusoria, a trick of nature

An ARSA or ‘arteria lusoria’ is found in 0.7–2.0% of patients [1]. It results from the persistence of a portion the embryological right dorsal aorta that should normally regress [2,3]. Tanaka et al. in a comprehensive review of KD suggest that high rates of rupture and dissection associated with these vascular anomalies may be explained by a combination of unusual mechanical stress on the walls of aberrant vessels and pathological involution of abnormal vascular tissue [4–10].

Current treatment paradigms

The presence of a Type B IMH involving an ARSA with KD is exceedingly rare with only one case found in the literature [11]. Type B aortic dissections associated with ARSA and KD are also rare but case reports are available all of which were managed with open surgery [12–18].

The acute management of a Type-B acute aortic syndrome (AAS) is initially dependent on whether it is complicated or uncomplicated. Traditionally, initial management of uncomplicated patients is by optimal medical therapy. There is a subgroup of patients in this so-called uncomplicated category, which are more at risk of developing aortic deterioration leading to early morbidity and mortality. In patients with IMH these include persistent pain despite requiring opiate analgesics, hemodynamic instability despite being on multiple antihypertensives, native aortic diameter >40 mm, mean diseased aortic diameter >60 mm, intimal defect or entry tear on the inner curve of the aorta, significant periaortic hemorrhage, pleural effusions and focal intimal disruption [19]. PAU were previously thought to be a relatively benign entities; however, there is growing evidence to suggest that IMH with an associated PAU have a higher rate of progression to complication than classical type B aortic dissection or IMH without PAU and may warrant more aggressive management [20–23].

If TEVAR is considered for treatment of TBAD cases, the generally accepted wisdom is to wait to the subacute phase that has been defined as after the initial 2 weeks of symptom onset. The rationale for this is that in the most acute phase, the aorta is at its most fragile. Historically treatments of acute phase TEVAR for TBAD were complicated by a high incidence of retrograde Type A aortic dissection.

Generally treatment for uncomplicated ARSA with KD is also typically conservative. Tanaka et al. [6] described high rupture and dissection rates in patients regardless of diverticular size, leading to the recommendation for surgical intervention for Kommerell’s with >5 cm maximal diameter or ARSA orifical diameter exceeding 3 cm. None of our cases met the recommended size criteria for intervention, and no case presented with compressive symptoms. In our first case it appears that the involvement of the ARSA in the AAS was incidental with the culprit lesion being a descending thoracic aorta PAU. In the second case, there was no clear intimal disruption associated with the IMH, and the possibility of the originating lesion being associated with the KD cannot be ruled out.

Precedence for management of these cases, particularly endovascular treatment was not available. Only one case in the literature describes an attempt at conservative management of a Type B AAS involving an ARSA and KD reported by Guzman and colleagues. In this case persistent pain necessitated open surgical repair [16]. Feraz de campos [11, 24] report a case of conservative management of a thoracic aortic aneurysm with IMH and ARSA; however, there is no longer-term follow-up reported. Despite our initial trials of conservative management, both patients had persistent opiate dependent pain. Our experience would suggest that ARSA with KD in IMH and PAU represents an additional risk for progression to complicated AAS and should be considered an additional criterion for intervention for AAS, irrespective of KD size criteria and traditional TBAD classification.

Choices for surgical repair

This case series demonstrate successful hybrid TEVAR with extra-anatomic de-branching. Single-stage procedures were performed with TEVAR reinforcing the aorta and associated IMH, bilateral open C-S revascularizations and endovascular occlusions of the ARSAs and LSAs. An illustration of the two repairs for the above cases is demonstrated (Fig. 5).

Diagram representing hybrid supra-aortic debranching, TEVAR and endovascular occlusion of subclavian origins.

There is no standard surgical approach for Type B AAS involving an ARSA. The use of an open surgical method with left thoracotomy, aortic replacement and revascularization of the right subclavian artery is fraught with significant morbidity and mortality. The use of TEVAR avoids the thoracotomy and aortic and pulmonary related morbidity. The limiting factors for TEVAR are related to the size and quality of the sealing zone in the aortic arch [22] and then need for adjunctive treatment to the ARSA. The ARSA needs to be disconnected to stop retrograde arterial flow and then revascularization is generally performed with C-S bypass or transposition. Another option would be to occlude the ARSA and not revascularize; however, high levels of ischemic complications in patients who underwent ARSA ligation have led to the recommendation that aberrant subclavian artery flow should be preserved [6].

Total endovascular treatment of this problem has been previously reported with preservation of the left subclavian artery origin with a chimney graft and coil occlusion of the ARSA origin without revascularization [22]. Ding et al. [25] report one case of endovascular aortic repair with periscope technique to preserve perfusion to the ARSA.

In our cases, a hybrid endo-open repair allowed the creation of an adequate proximal landing zone, by facilitating the TEVAR coverage of the ostia of both the left subclavian and ARSA after bilateral upper extremity extrathoracic revascularization. Of particular interest in the first case, the initial trial of conservative management and delay in definitive surgical intervention increased the difficulty of the revascularization component. The IMH progressed further into the ARSA to involve the site of the C-S bypass, necessitating bypass onto the axillary artery.

The pre-existence of the KD, an area of known arterial weakness, puts this small subgroup of TBAD patients at higher risk than those without this anomaly. The failure of optimal medical therapies in these two patients is telling and suggests that medical treatment alone is unlikely to be an adequate protective option for this complex patient group. Though these KD patients may not have the traditional criteria of what is deemed to be a complicated TBAD, this series of cases suggests that the presence of a KD with TBAD should be a warning sign; that this is another new subgroup of TBAD morphologies, along with traditional criteria such as aortic size, as a subgroup that should be considered for TEVAR as the primary method of treatment.

In addition, the rapid progression of these patients despite optimal medical therapy (OMT) and the complex and deteriorating state of the ARSA, suggest that these patients should be treated by TEVAR in the acute phase rather than waiting for the subacute timeframe.

CONCLUSION

We present a series of AAS variants, all involving ARSAs with KD. This includes the first PAU with IMH involving a KD reported in the literature. Our institution’s experience suggests that the presence of AAS in ARSA and KD invariably progress and that optimal medical treatment is inadequate to control acute disease progression. We describe the use of TEVAR, in conjunction with bilateral subclavian artery occlusive procedures combined with bilateral C-S artery reconstructions as a safe and durable treatment strategy for this difficult management problem. We believe that the presence of KD in the context of AAS and TBAD, in particular, should be classified as an additional anatomical criterion to stratify these TBAD patients as higher risk of aortic morbidity and that early TEVAR intervention should be considered in this subgroup of patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

There are no conflicts of interest to declare and no financial interests in writing of this case series.

FUNDING

No funding was provided in writing of this paper.