-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

H Woodun, H Woodun, R Vetrivel Vedachalam, H Fassihi, P Achar, Bilateral cochlear implantation in a young patient with xeroderma pigmentosum (XP-D) and progressive sensorineural hearing loss—How to do it?, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 1, January 2022, rjab594, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab594

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), a rare genetic skin condition, causes ultraviolet (UV)-induced neoplasms and possible neurological deficits including sensorineural hearingloss.

We present the first case in literature of bilateral cochlear implantation (CI) in a patient with XP-D with neurodegeneration. Multi-disciplinary team members (national XP team, dermatologist, anaesthetist, theatre team, biophysicists) were involved. UV exposure from equipment and areas where the 14-year-old patient would track was measured. Maximum possible surgery was performed under operating headlights to limit higher-UV microscope exposure. Its bulb light intensity was reduced to achieve safe UV level (0–10 μW/cm2). Skin was protected under surgical drapes. Challenges included drilling unpredicted hard thick bone under low-intensity light and requiring bulkier Nucleus®-7 processor due to unanticipated increased scarring. A delayed left facial weakness was resolved with steroids. He is undergoing hearing rehabilitation.

This highlights challenges of CI in XP. Its impact in preserving cognition and on neurodegeneration should also be observed.

INTRODUCTION

Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) is a rare, autosomal recessive disease affecting 1 per one million in the USA and Europe but is more common in Japan and parts of Africa [1]. It causes photo hypersensitivity to ultraviolet (UV) exposure associated with defective repair of sunlight-induced DNA damage. Patients present with severe sunburn on minimal sun exposure in ~50% of cases which can be misdiagnosed as atopic dermatitis or sunburn [1].

XP results from defects in the nucleotide excision repair pathway, leading to seven XP complementation groups: XP-A through to XP-G. XP-A, XP-B, XP-D or XP-G genes predispose patients to progressive neurological degeneration; ~25% of 106 XP patients seen at the NIH Clinical Center [2]. XP-A and XP-D patients had the highest prevalence of sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL), dysarthria and difficulty walking due to sensory peripheral neuropathy [1].

SNHL contributes to developmental delay, regression and worsening quality of life. We present the first case in literature of a 14-year-old male with XP-D with neurodegeneration who undergoes cochlear implantation (CI) for SNHL following environmental and surgical technique adaptations.

CASE REPORT

A 14-year-old male with XP-D with neurodegeneration was referred to the regional tertiary otorhinolaryngology centre with severe to profound bilateralSNHL.

His background includes XP which affects his skin, neurodevelopment and hearing. Serial neurological assessments revealed plateauing of language, intellectual and visuomotor skills. He requires adaptations: UV blocking glasses, regular sunscreen creams, UV-protecting films in all windows, and vitamin D supplementation. He underwent grommets insertion for recurrent otitis media at 2 years. His hearing deteriorated, and at 6 years, he needed hearingaids.

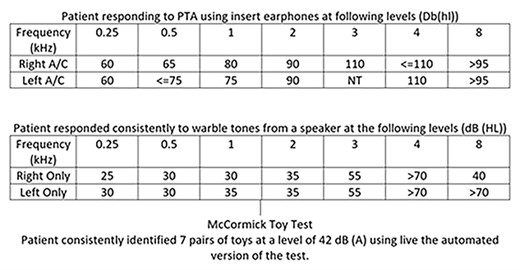

Examination revealed a dull right tympanic membrane and left myringosclerosis. Tympanometry indicated normal bilateral middle ear function. Audiometry is shown in Fig. 1, fulfilling the criteria for bilateralCI.

Pure tone audiometry (PTA) results of patient at presentation for consideration ofCI.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the internal acoustic meatus and central auditory pathway was normal, and skin thickness was 6 mm suggesting the use of a lighter Nucleus® Kanso® Sound Processor. However, there were few concerns.

Our first concern was the requirement of MRI in patients with XP-neurodegeneration as cochlear implants render MRI scans more complex in terms of technique and create artefacts. The national XP team was contacted, and we were reassured that MRI may not be needed as the disease progression is known.

The other concern was patient safety and dermatological complications when exposed to the surgical light field. Preoperative arrangements were discussed in multi-disciplinary teams (MDT) including XP specialist nurse, paediatric dermatologist, anaesthetist, theatre team and biophysicist. A thorough consent procedure was undertaken with parents who agreed to proceed.

A UV reader, Solarmeter® Model 5.7, was acquired and calibrated before and postdelivery to our surgical department. UV-A and UV-B levels were measured in relevant equipment and all areas where the patient would track during his stay within hospital, including surgical operating lights, microscope lights and anaesthetic laryngoscope lights: UV-B levels were undetectable, UV-A levels with the UV filter ranged from 4 to 18 μW/cm2. Surgery was planned with microscope bulb light intensity 5–7 (usual bulb intensity used is 7–10) so that the hypothetical safe level of UV (0–10 μW/cm2), suggested by the national XP team, was achieved. Anaesthetists were alerted early, and an overnight stay was planned instead of daycase.

On the operative day, he applied extensive sunblock. UV exposure intra-operatively was reduced by protecting the skin under surgical drapes and performing maximum surgery under operating headlights safely to limit exposure under higher-UV microscope lights. During cortical drilling under low-intensity light, the patient’s thick and hard temporal bone was an unexpected challenge. A total of 3 days postoperatively, he was readmitted with left facial weakness. Initial concerns included unpredicted tissue necrosis due to XP or damage over the facial canal but he improved with steroids and antibiotics, which confirmed an aetiology of postoperative oedema.

Another encounter was the Kanso® 2 Processor not adhering well to the receiver-stimulator due to unforeseen postoperative increased skin thickness related to scarring. Kanso® processor was swapped to Nucleus® 7 Sound Processor.

He is undergoing hearing rehabilitation and psychological therapy with MDT involving dermatology, psychologist, implant audiology, biomedical scientists, specialist nurses, speech therapists, paediatrics team, National XP team and teacher of the deaf, and has found the cochlear implant useful in terms of hearing and communication during his last visit 4 months after surgery.

DISCUSSION

Progressive SNHL contributed to our patient’s worsening quality of life. Totonchy et al. [3] discussed that the degree of hearing loss is correlated to neurological involvement. Patients with XP-neurodegeneration had significant hearing loss 54 years before unaffected population. Hearing declines more rapidly in the XP-neurodegeneration group, possibly because they accumulate DNA damage to their auditory system faster.

Pathophysiology of SNHL in XP suggests degeneration of the organ of Corti and spiral ganglion cells [4], patchy atrophy of the stria vascularis, severe loss of cochlear neurons and particularly dendritic fibres compared with age-match controls [1]. CI theoretically would have limited benefits as CI work by directly stimulating the spiral ganglion [5]. However, it is difficult to quantify the loss of neurons and identify the exact pathogenesis for hearing loss in these patients. Successful outcomes have been seen in patients with retrocochlear pathology [6]. Considering all these caveats, CI with appropriate consenting on a guarded prognosis was offered.

XP patients are 10 000 times more prone to non-melanoma skin cancers and 2000 times for melanoma [2]. Evidence on the effect of light on the inner ear is lacking. Therefore, national and local advice and significant adaptations are important to minimise iatrogenic UV exposure to patients. However, reduced light intensity makes drilling hard thick temporal bone (which may be due to faster accumulation of DNA damage [7]) challenging.

Morris et al. [8] report the case of a 25-year-old patient with Cockayne syndrome (CS) and photosensitivity, close to XP-CS complex [9], who underwent CI and maintained good function at 3.5-year follow-up but no technical details were specified. Another case at 21 years old, however, did not benefit from CI [8]. A total of two paediatric patients with CS underwent successful management of progressive SNHL with CI [10].

There is no cure for XP, and it is useful to predict patients with XP with neurological degeneration, as prognosis is poor [1]. Targeted novel therapies (including rapamycin, which reactivates autophagy; amitriptyline, which restores synaptic contacts by triggering neurite growth; antioxidant therapy with CoQ10) are being investigated [11] but management is mostly preventative and symptomatic, including regular skin and ophthalmological examinations. Audiometric status, XP complementation group and acute burning on minimal sun exposure are important early indicators [2]. Exposure to loud noise should be avoided, and regular audiologic screening and monitoring is required to facilitate timely intervention [2].

Our case demonstrates that bilateral CI could be a management option for eligible XP patients to improve quality of life, albeit its impact in preserving cognition and long-term effect on neurodegeneration needs a careful follow-up.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Queen's Medical Centre, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust: 1. Nottingham Auditory Implant Programme Team 2. Medical Physics and Clinical Engineering Team 3. Queen's Medical Centre Theatre Team National XP team at Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust:4. Sally Turner, XP Clinical Nurse Specialist, 5. Other Team Members at National XP Service

References

- cicatrix

- cochlear implantation

- cognition

- sensorineural hearing loss

- nerve degeneration

- audiologic / aural rehabilitation

- skin disorders

- steroids

- surgical procedures, operative

- xeroderma pigmentosum

- genetics

- neoplasms

- skin

- facial paresis

- surgical drapes

- microscopes

- neurologic deficits

- headlamps

- light intensity

- dermatologists

- anesthetists