-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Masahiko Narita, Shingo Kunioka, Tomonori Shirasaka, Hiroyuki Kamiya, Micra leadless pacemaker for bridge use after explantation of infected permanent pacemaker system: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 4, April 2021, rjab094, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab094

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The extraction of a pacemaker (PM) lead may cause tricuspid regurgitation; however, in cases of device infection, surgical intervention or immediate PM system replacement is undesirable in the short term to prevent reinfection. We describe a case where Micra leadless PM was used as a bridge procedure to ensure an adequate period for antibacterial therapy and later replaced with a permanent PM system in the setting of PM pocket infection.

BACKGROUND

There are several reports of tricuspid regurgitation (TR) as a sequela of extracting implanted pacemaker (PM) leads. When explantation of a PM system is needed for proven or suspected device infection, we have found that implantation of the new conventional PM is advisable after a recovery window in which the infection can be adequately treated [1, 2]. Herein, we present a case of severe TR after PM lead extraction, successfully treated via Micra (Medtronic, MN, USA) leadless PM implantation, which resulted in a needed bridge to surgical intervention and conventional PM implantation.

CASE PRESENTATION

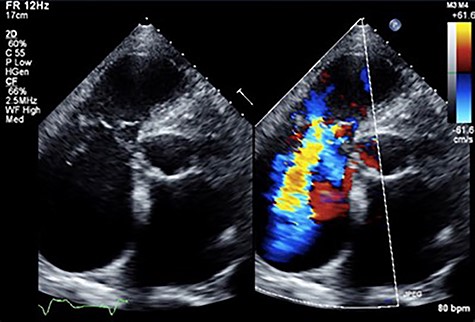

An 81-year-old male presenting with a PM pocket-associated infection was referred to our institution. Twelve years prior, a conventional PM was implanted for bradycardia and atrial fibrillation. A pocket infection was noted after the device generator was changed one month prior. We performed a complete pacing system extraction, but during explantation of a transvenous lead via simple traction, myocardial tissue adherent to the lead was concomitantly removed. Subsequently, the patient developed ventricular fibrillation. An immediate transthoracic direct-current cardioversion resulted in successful defibrillation. Postoperative transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed tricuspid valve destruction and severe regurgitation (Fig. 1). A hasty surgical repair of the tricuspid valve or implantation of new transvenous leads seemed undesirable at the time because of ongoing active endocarditis. In addition, with the hope that the patient could tolerate severe TR as he had moderate TR preoperatively secondary to his PM lead, we considered a leadless transcatheter pacing system, Micra implantation without tricuspid valve repair. Micra implantation procedures went well, and after sufficient antibacterial therapy, the patient was discharged stable (Fig. 2A).

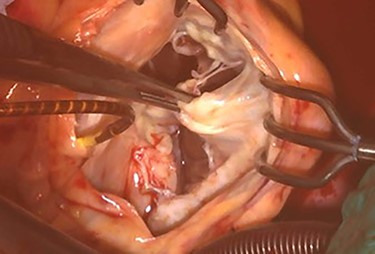

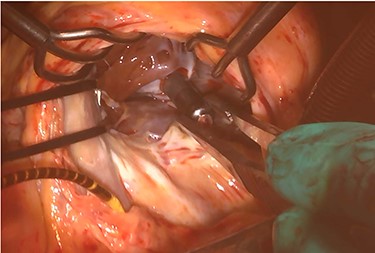

At his 1-year follow-up visit, the patient presented with shortness of breath on exertion and leg edema; thus, we decided to perform surgical correction. After median sternotomy, cardiopulmonary bypass was established with ascending aortic and bicaval venous cannulations. MyoPore (Greatbatch Medical, NY, USA) bipolar sutureless screw-in lead was attached to the left ventricle. A permanent PM was implanted, and left atrial appendage exclusion with AtriClip (AtriCure, OH, USA) was performed afterward. A right atriotomy was performed to facilitate exposure, wherein we found that the septal and posterior leaflets of the tricuspid valve were severely damaged (Fig. 3). Micra was placed over the right ventricular septum and was easily freed under direct vision (Fig. 4). After the leaflets were excised, an Epic (St Jude Medical, MN, USA) 33-mm bioprosthesis was implanted.

Chest X-ray findings; (A) immediately post-implantation of Micra (B) after tricuspid valve repair and implanted epicardial PM system.

Intraoperative photograph; septal and posterior leaflet of tricuspid valve are severely damaged.

Intraoperative photograph; Micra was retrieved under direct vision.

The patient had an uneventful postoperative course during his hospital stay and was discharged on the 22nd day after the operation (Fig. 2B). Postoperative TTE showed trace TR. Six months after the operation, the patient was undergoing outpatient clinical monitoring and was reportedly well.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the application of Micra as a bridge procedure prior to permanent PM implantation. Due to the success of the bridge procedure, we were able to safely perform a more definitive surgical procedure for TR as well as impant a new PM device after a sufficient period, allowing for adequate recovery from an infected PM system explantation and subsequent antibacterial therapy.

TR worsening following PM lead extraction has been described in several studies with a reported incidence of 11–15%, and the increasing risk with lead implant duration, use of mechanical tools and younger age at extraction [3–5]. However, it has been suggested that TR after extraction was not associated with the incidence of right-sided heart failure or subsequent need for tricuspid valve surgery [3]. In the presented case, although the patient was followed-up with an expectation of tolerance for severe TR, surgical intervention for TR was unavoidable due to the progression of heart failure. Thus, one should be aware that the possibility of TR worsening as a sequela of PM lead extraction and these patients require close observation even if a surgical intervention is rarely eventually needed.

While there are no guidelines for the appropriate timing of reimplantation after explantation of a PM system for device infection, in our current clinical practice, corrective procedures are recommended after an adequate period of antibiotic therapy. It has recently been reported that leadless PM placement after infected conventional PM explantation could be a viable option in PM-dependent patients [6, 7]. In the presented case because of leadless PM implantation, the patient underwent a sufficient period of antibacterial therapy without recurrent device infection.

Our search of the literature revealed no report of applying leadless PM as a bridge procedure. As previously described, leadless PM implantation could be a reasonable option after PM explantation for device infection. On the other hand, leadless PM, as with conventional PM, will need to be replaced due to generator limitations. In the presented case, we performed tricuspid valve repair and freed the leadless PM simultaneously. Of note, under direct vision, leadless PM could be retrieved safely. From this experience, we suggest that leadless PM as bridge procedure could be one option for patients who will possibility to need a more definitive surgical intervention in the future.

CONCLUSION

We encountered a case of Micra leadless PM implantation as a bridge procedure prior to further surgical procedures in a patient who underwent PM extraction due to device-related infection. This allowed us an adequate period for antibacterial therapy after device explantation.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Data supporting the conclusions are included in the article.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

M.N. wrote this case report. T.S. and H.K. supervised the writing the report. S.K. and H.K. performed the surgery. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Cactus Communications (http://editage.jp) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was obtained from the families of the patient for scientific activity including publication of this case report.