-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Can Sezer, Murat Gokten, İnan Gezgin, Aykut Sezer, Ali Burak Binboga, Mehmet Onay, Spontaneous migration of a bullet in the cerebrum, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 4, April 2021, rjaa420, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa420

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Herein, we report the case of a 32-year-old man who experienced spontaneous migration of a bullet within the brain following a gunshot injury. Emergent computed tomography revealed the bullet located in the posterosuperior side of mesencephalon. During follow-up after 10 days, the neurological status of the patient had worsened. Computed tomography revealed that the bullet had migrated posteriorly and lodged in the occipital lobe. Although a few studies have reported on the spontaneous migration of a bullet within the brain, the present case is unique as the patient examination changed with migration. We recommend serial imaging and surgery in cases of bullet migration in the brain.

INTRODUCTION

Gunshot head injuries (GHIs) are a fatal type of cranial trauma. However, the migration of intracranial bullets is rare, accounting for 0.06–4.2% of all GHIs [1]. The mortality rate is 51–84%. Although GHIs are becoming more common, their management remains controversial.

Intracranial bullets may cause late complications, including intracranial abscess, seizure, ventriculitis and obstructive hydrocephalus. The mechanisms of bullet migration vary. The primary accepted theory is the pulsatile nature of the cerebral ventricles, with a significantly greater gravity of the bullet than that of the brain tissues [2].

Herein, we describe a case of the spontaneous migration of the bullet; the bullet entered through the left parietal lobe and traveled to the contralateral mesencephalon and cerebellar hemispheres, resulting in an improbable survival of the patient.

CASE REPORT

A 32-year-old man was admitted to hospital. He had sustained a single gunshot wound on the left parietal region from a low-caliber weapon. He was immediately intubated. During admission, the patient was unresponsive to commands; however, his vitals were stable. Painful stimuli elicited purposeful movements of the right arm and leg. Moreover, left hemiparesis was observed. He could not open his eyes, and bilateral pupils were equal and reactive to light.

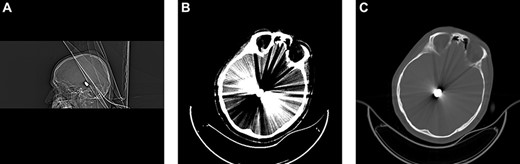

Emergent unenhanced head computed tomography (CT) was performed, which revealed a bone defect in the left parietal region and a metallic object in the posterosuperior side of the mesencephalon. The bullet had entered through the left parietal lobe. Associated hemorrhage was observed along its trajectory in addition to subarachnoid hemorrhage and minimal brain edema. However, the metal artifacts obscured the damage (Fig. 1). The entry wound was debrided and sutured. The patient was admitted to the neurosurgical intensive care unit and was conservatively treated with prophylactic antibiotics, antiedema medications, sedatives (pentobarbital) and antiepileptic drugs.

Brain CT upon admission revealed the bullet fragment located deep to the convexity of the skull. (A) Sagittal bone window. (B) Brain. (C) Axial bone window.

A follow-up control head CT was performed 1 day after admission. No significant change was observed from the initial CT. The patient’s vital signs and neurological status were stable.

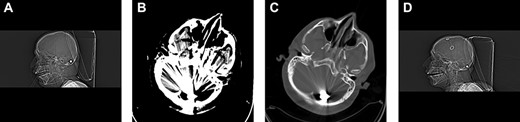

After 10 days, the patient’s neurological status worsened. Painful stimuli elicited purposeful movements of the right arm and leg. However, further examination revealed left hemiplegia with anisocoria. Emergent unenhanced head CT revealed the spontaneous migration of the bullet from the posterosuperior side of the mesencephalon to the occipital region on the left side (Fig. 2). Moreover, hydrocephalus improved. The patient’s cerebrospinal fluid was thoroughly examined for the presence of bacteria. However, the cerebrospinal fluid was sterile. Surgery was performed immediately on the ventriculoperitoneal shunt to treat hydrocephalus. On the third day after surgery, the patient could follow simple commands and showed increasingly purposeful movement on the right side. However, left hemiplegia and anisocoria did not improve. The bullet appeared removable. Therefore, we decided to remove the migrating bullet after the patient’s neurological status improved.

Follow-up CT after 10 days of admission revealed inferior and retrograde migration of the bullet to the left cerebellar peduncle. (A) Sagittal bone window. (B) Brain. (C) Axial bone window. (D) Postshunt operation control. Sagittal bone window. Ventricular catheter is observed.

During the next 3 weeks, the patient’s status improved continually. He received active physical therapy during the postoperative period and was transferred to the rehabilitation center after 4 weeks for the treatment of residual left hemiplegia. During rehabilitation, the patient aspirated stomach contents and then presented with fever and pulmonary infection. The patient was treated with antibiotics. However, he died from pulmonary infections.

DISCUSSION

Spontaneous migration of intracranial bullets is extremely rare. Penetrating bullets create a destructed pathway in the parenchyma. Following injury, early edema in the brain does not permit the bullet to migrate. Time to migration is 2 days to 3 months. The earliest documented case of bullet migration occurred 36 hours after trauma [3].

Nonetheless, the management of migratory bullets remains controversial. Some authors have recommended that the bullet should be removed from the brain if it is accessible and does not cause additional neurological damage. Bullet migration in the brain is primarily attributed to gravitational forces and the sink function of a heavy body [1].

In a retrospective study of a series 213 head gunshots, there were 9 spontaneous bullet migration cases (4.2%) [1]. In another series, the incidence of bullet migration ranged from 0 to 10%.

Castillo-Rangel et al. [3] have reported that the ventricular system supports migration. Moreover, the flow of cerebrospinal fluid and pulsation facilitates bullet migration. Fujimoto et al. [2] have reported on the migration of an intraventricular migrated to the aqueduct of the Sylvius, which caused hydrocephalus.

Kocak and Ozer [4] have emphasized the outcome indicating the absence of neurological deficits. The present case demonstrated that the quality of survival can be improved despite the involvement of vital structures.

The type of damaged tissue, density of the bullet compared with that of the brain tissues and gravitational forces are significant factors that affected bullet migration in our patient.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.