-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Obed Rockson, Mohammed Mhand, Houssam Aabdi, Tariq Bouhout, Tijani El Harroudi, Badr Serji, Colostomy orifice complications: a case report of a prolapsed colostomy with necrosis of the eviscerated greater omentum, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 11, November 2021, rjab513, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab513

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Evisceration and necrosis of the greater omentum at the site of a prolapsed colostomy is a rare situation. Considered an early stoma complication, it often occurs during the first month after surgery. We report the observation and our attitude to such a situation in a 56-year-old patient who underwent initial surgery for a locally advanced rectal adenocarcinoma after receiving neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy. A loop colostomy for decompression was performed due to large bowel obstruction. On the 10th day after surgery, he was readmitted for an oedematous prolapsed colostomy and a necrotic end of the greater omentum, which eviscerated through the colostomic hole, secondary to severe ascites. Emergency re-intervention involving resection of the prolapsed stoma with the necrotic segment of the omentum was performed. The three factors associated with the development of this rare peri-colostomy complication were: emergency surgery, locally advanced rectal tumor, and increased intra-abdominal pressure.

INTRODUCTION

The necrosis of eviscerated end of the greater omentum through the orifice of a prolapsed stoma is a rare entity. It is considered a non-dermatological complication observed in 1–2% of cases of early stoma complications [1, 2]. They always occur in three situations: when the musculoaponeurotic orifice is too large, a hypoplastic abdominal wall, or an increase in intra-abdominal pressure. Immediate surgical re-intervention is necessary to reduce the high morbi-mortality associated with this rare entity [3]. We decided to report this case due to its rarity and high morbidity, discussing the contributing risk factors, diagnostic assessment, management and prevention.

CASE REPORT

A 56-year-old patient, active smoker at the rate of 20 pack-years was referred to our oncology center for the evolution in the past 5 months of a locally advanced well-differentiated, infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the middle rectum located at 8 cm from the anal margin. The patient received total neoadjuvant therapy based on a long course of pre-operative radiotherapy associated with the addition of oxaliplatin to standard 5-fluorouracil based chemoradiotherapy. A loop colostomy for decompression for large bowel obstruction and high intra-abdominal pressure secondary to ascites of great abundance was performed. We suctioned ~5 liters of the ascitic liquid without placing intra-abdominal drains. Ten days later, with a functional colostomy, he developed prolapse and oedematous colostomy due to intra-abdominal hyperpression. Physical examination revealed a cachectic patient with signs of mucocutaneous dehydration, malnutrition, a distended abdomen and intense pain at the colostomy site.

Biological work-up showed pancytopenia with a hemoglobin level of 11.3 g/dl, erythrocytes of 3.21 M/mm3, platelets of 106 000 mm/m3, hypokalaemia of 2.75 mEq/L, natremia of 137 mEq/L, creatinine of 7.4 mg/L, uremia of 0.29 g/L, prothrombin level of 100% and hypoalbuminaemia of 20 g/L.

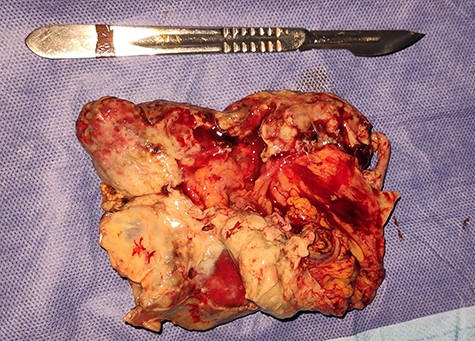

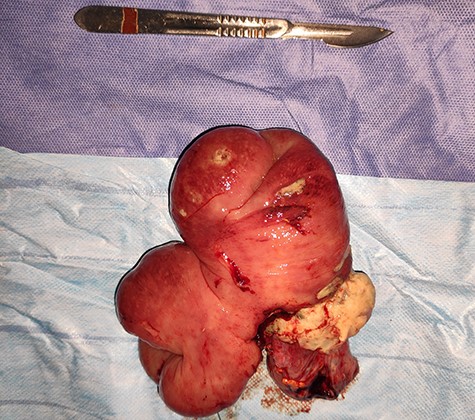

After fluid resuscitation and correction of hypokalaemia, the patient underwent urgent surgery for stoma revision, with a surgical approach through the colostomy site. After an elective peristomal incision, the unusual finding was necrosis of the eviscerated segment of the greater omentum through the colostomy hole of the prolapsed stoma (Fig. 1), and the presence of ~2 liters of ascites. After aspiration of the ascitic fluid, the eviscerated and necrotic end of the greater omentum and the protruding stoma were resected (Figs 2 and 3) by incising the mucocutaneous junction, mobilizing and amputating the prolapsed segment. A new, more proximal stoma was then rematured. Two drains were placed in the pouch of Douglas and the diameter of the peritoneum aponeurotic hole was tightened, by using simple suturing, with separate stitches of unabsorbable thread. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on Day 7. After two months of clinical follow-up, the patient is doing well with the resolution of ascites and is being re-evaluated for tumor resection.

Oedematous and prolapse colostomy with necrosis of the greater omental eviscerating through the colostomy site.

Surgical specimen showing the resected necrotic segment of the greater omentum.

Surgical specimen of the resected prolapsed and oedematous colostomy.

DISCUSSION

General stoma complications have steadily decreased over the last twenty years, but complications at the stoma site are common and occur mainly in the immediate postoperative period [4]. Most if not all of the complications are linked to a lack of technique. The performance of a colostomy, considered by many surgeons to be a simple operation, can have a relatively high rate of complications: around 10–60%, with morbidity of between 20 and 30%, and mortality of around 1% [1, 3, 5]. Regardless of the type of colostomy, a distinction must be made between early complications occurring during the first month after surgery and late complications. Necrosis, retraction, mucocutaneous separation, stoma evisceration and parastomal abscess are considered early complications, whereas parastomal hernia, prolapse and retraction are late complications [3].

Stomal or peristomal evisceration is a clinical manifestation that often occurs between the sixth and seventh postoperative days. It is defined as acute dehiscence of the surgical stomal incision. The risk factors for this stoma-related complication are anemia, increased intra-abdominal pressure (resulting from ascites, cough, acute urine retention and vomiting), GI cancer surgery, emergency surgery, surgical re-intervention, surgical duration >3 hours, malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, older age >65 years, multiple organ failure, digestive fistulas, systemic arterial hypertension, hypoproteinemia, jaundice, surgical wound infection, peritonitis, inadequate suture material, corticotherapy, chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy and technical failure, among others [3, 6–8]. Relevant to our case, emergency surgery, malignant rectal tumor and increased intra-abdominal pressure due to ascites were considered the three main triggering factors. Stoma prolapse is a full-thickness protrusion of the bowel through a stoma occurring in 2% of colostomies [9]. Loop colostomies protrude more frequently than end colostomies and usually involve the efferent (distal) limb. It is considered a sliding prolapse when it is due to an increase in intra-abdominal pressure. The risk factors for this complication are all patient-related and include old age, obesity, and bowel obstruction at the time of stoma creation, as was in our case [3, 10]. Symptoms may include pain, skin irritation and, in rare cases, obstruction, incarceration or strangulation [3].

Emergency re-intervention is indicated with the reintegration of viable omentum into the abdominal cavity or resection in case of necrosis. The surgical approach to the evisceration can be either by exploratory laparotomy with the creation of a new stoma or by a procedure limited to the colostomy site [2, 5, 11]. Stoma prolapse repair includes the reversal of temporary stoma (when possible and feasible), resection, revision or relocation while performing extra-peritoneal tunneling and adapting the size of the aperture to the intestinal size [12]. In our case, both complications of stoma prolapse and greater omentum evisceration were due to ascites and not to a lack of technique. We propose that intra-abdominal suction drains should be placed when performing a loop colostomy for large bowel obstruction due to rectal tumor with the presence of significant ascites in order to prevent recurrence and thus complications of the stoma.

In conclusion, evisceration of the greater omentum through the stoma orifice of a prolapsed colostomy can be a challenging entity for clinicians especially when it is covered by necrotic segments. It is critical for the surgeon to possess a thorough understanding of the multiple factors involved in the occurrence of this complication to be able to manage them accordingly.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors testified to the care of the patient and the writing of the manuscript. The authors have read and agreed with the contents of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.