-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hiral Amin, Ruben D Salas-Parra, Lauren Stantley, Nirmala K Rajee, Vinayak S Gowda, Unusual presentation of rectal squamous cell carcinoma perforation—case report and literature review, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 1, January 2021, rjaa565, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa565

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This is an unusual case of an obstructive rectal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), causing perforation and a pelvic abscess, requiring source control and diverting colostomy. A 50-year-old female with chronic constipation presented with worsening right buttock pain for 1 month. On exam, the patient reported right hip tenderness. A computer tomography (CT) revealed rectal wall thickening with a presacral abscess. Due to the concern of rectal perforation with abscess she was taken to the operating room for proctoscopy with biopsy, colostomy diversion and drainage of the abscess over the right buttock. Pathology reported invasive rectal SCC. Rectal SCC presents similarly to rectal adenocarcinoma but its diagnosis must include special markers for cytokeratins. The treatment approach is controversial but adequately treated offers better survival than rectal ADC. Rectal SCC is rare and treated with chemoradiation however it must also be tailored to the variable acute presentations.

INTRODUCTION

Rectal squamous cell carcinoma is a rare finding with only a few case reports published in the past [1–3]. Most rectal cancers are adenocarcinomas (ADC) with a clear treatment algorithm. Etiology and management of rectal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) are therefore unclear given the range of presentations with little experience known to medicine.

We report an unusual case of rectal SCC presenting with a large obstructive rectal mass, causing perforation and a pelvic abscess, which required source control of the infection and diverting colostomy.

CASE REPORT

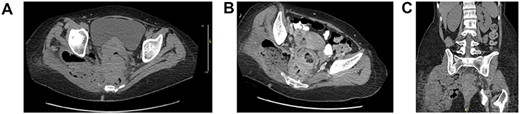

A 50-year-old female with chronic constipation presented to the emergency department complaining of severe right buttock pain, limiting her ambulation for a month, associated with unintentional weight loss of 70 pounds in 3 months. She had no prior colonoscopy. Hemodynamically stable on presentation with right hip tenderness. A CT abdomen and pelvis revealed eccentric rectal wall thickening, pelvic adenopathy, with a presacral abscess of 7.4 × 1.8 × 10.2 cm that appeared to be connected to the right buttock via sciatic notch with the involvement of the right adnexa and uterus as well (Fig. 1). Tumor markers were negative.

Axial (A, B), coronal (C) CT abdomen and pelvis without contrast: complex right adnexal mass containing gas, measuring ~4.5 × 3.5 cm in size. This does appear to be contiguous with small bowel on the right side of the pelvis. Wall thickening of the rectum noted. Perirectal adenopathy, measuring up to 1.4 cm in diameter. There is perirectal soft tissue, which extends to the mesial rectal fascia, posteriorly adjacent to the sacrum and coccyx and to the right side of the pelvis. There are perirectal air collections noted posteriorly. There is a large complex collection which extends through the sciatic notch into the right gluteus muscle, measuring ~9 × 6 cm, containing air and possibly feces. This collection also extends in inferiorly to the level of the ischial spine.

Due to the concern of possible stercoral versus malignant perforation with pelvic and gluteal abscess, she was taken to the operating room for proctoscopy which revealed a large, obstructive, ulcerated and bleeding mass 4 cm proximal to anal verge that was biopsied. Subsequently, a transverse loop colostomy was created, and a separate transverse incision was made over the right buttock with superior extension to the iliac crest to drain 300 cc of purulent fluid.

She did well postoperatively. Further metastatic workup was negative. Pathology was remarkable for invasive rectal SCC with focal basaloid features (Fig. 2). She was then referred to oncology for further management.

![Histopathology invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the rectum: (A) normal anorectal junction, and squamous cell carcinoma of the rectum [Hematoxylin and eosin 4×]. (B) Squamous cell carcinoma with basaloid features with mitosis [Hematoxylin and eosin 40×]. (C) Squamous cell carcinoma with positive stain for P16 [P16 40×].](https://oupdevcdn.silverchair-staging.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/jscr/2021/1/10.1093_jscr_rjaa565/2/m_rjaa565f2.jpeg?Expires=1773724069&Signature=eEU77n7WuX9Gn323Fdz0zBz~9J6CyqFVZiXdb6eS7raKCM0eYihC6cyuflcODs-dLkjcP0xJuQqM-VJutBCJYvRtcoYdPvKuItN1WmTcR~U40j~jxW79te8Add1VvNLn5OxGjmWaLacx3IUt7XVap9U45PFxglsJXR4Klz3mJjV5FewlFRCXpm239GK2ljaoq1CqcKmdUUB8NNUB8a1p~BzJY25daIo868-TWWGL0tmhjfPteCE0P2t~O3io8qzIaAM0VOutudQu~wfeotN5m4tg-cp1tJ6Ss-crEosZg~aBIL7bQFGLD5-MT9GQGHxmVfHbdFU9xiwZdZkoT~~m0g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIYYTVHKX7JZB5EAA)

Histopathology invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the rectum: (A) normal anorectal junction, and squamous cell carcinoma of the rectum [Hematoxylin and eosin 4×]. (B) Squamous cell carcinoma with basaloid features with mitosis [Hematoxylin and eosin 40×]. (C) Squamous cell carcinoma with positive stain for P16 [P16 40×].

DISCUSSION

Rectal SCC is extremely rare, encompassing 0.25% of the total colorectal cases [1–4]. Patients diagnosed with SCC of the rectum have ranged from 40 to 90 years old, with an average age of 60, more commonly in females, with no apparent ethnic or geographical predisposition [5]. Pathophysiology is based only on hypotheses related to metaplastic transformation of columnar to squamous epithelium, chronic inflammatory states (radiation, parasitic infection) and transformation of pluripotent stem cells into squamous differentiation [1, 2, 4, 6]. Association with human papilloma virus (HPV) is not as clear as for ADC, but could be involved in the transformation of ADC into SCC [1]. Staining with p16 potentiate this hypothesis in our case.

In order to meet the criteria for rectal SCC the tumor should not be metastatic from a distant site, should not have a squamous cell-lined fistulous tract, and should not be an extension of SCC of the anus [1–3]. Weight loss, abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, change in bowel habits are some of the symptoms, associated with an obstructive mass found on sigmoidoscopy as in our case [1–4]. Retroperitoneal perforations of the large bowel are rare [7]; if perforation occurs gradually, it forms a localized pericolonic abscess at the perforation site rather than florid intra-abdominal sepsis. [8]. Interestingly, our patient presented with a perforation of the rectum causing a pelvic abscess likely related to delay in the presentation which has been not reported. Since retroperitoneal abscesses without cause are rare [7], it is likely that our patient’s abscess was a complication of a primary undiagnosed rectal SCC or secondary to stercoral perforation. Differentiation of either is critical in determining the appropriate treatment plan and predicting the prognosis of the patient [8]. Because the diagnosis of suspected malignancy was compounded by an abscess, a transverse loop colostomy and abscess drainage for temporization was performed until further workup could be completed. Patients with colon cancer perforation show eccentric wall thickening at the distal portion, and pericolonic lymph nodes [5, 8]. Nodal involvement of SCC demonstrated worse prognosis [9]. Overall 5-year survival for rectal SCC was found to be 48.9% [significant variation by stage; Duke B 50%, Duke C 33% and Duke D 0% [4]], compared with 62.1% for ADC [5].

Workup of rectal SCC includes tumor markers (CEA, CA 19-9) and CT or magnetic resonance imaging depending on the presentation. Colonoscopic biopsies of any abnormalities are crucial. Transrectal endoscopic ultrasound provides improved local lymph node evaluation [3, 4, 6]. Other markers such as cytokeratins AE1/AE3, CK 5/6 (34BE12 stains CK5), and p63 stain for cells of squamous origin assist in the differentiation from rectal ADC [5]. Cytokeratin CAM5.2 aids in the differentiation of rectal from anal, characteristically staining for rectal squamous cell or ADC, but not anal SCC [5]. Staging focuses on the importance surrounding the level of invasion through the rectal wall, nodal involvement and presence of distal metastasis. Rectal SCC has the same route of lymphatic spread as ADC to the liver, lung and bones [5]. Patients with diagnosis of rectal SCC present more commonly with locoregional disease [5]. Features associated with poor prognosis are ulcerated or annular carcinomas, node-positivity and advanced stages [6].

Rectal SCC is a rare malignancy for which consensus of the ideal mode of treatment is lacking. Historically, rectal SCC patients were managed similarly to rectal ADC, primarily relying on low anterior resection which is reserved for proximal 2/3 rectal lesions, and abdominoperineal resection which has significant morbidity and mortality but allows to explore advanced disease [9]. Surgical approach is the gold standard treatment for colorectal SCC according to some authors within the existing literature. The option of local excision would be limited to low-risk T1 lesions, characterized as being well-differentiated, without lymphovascular involvement, nodal or metastatic disease [5]. Studies have suggested improved outcomes with preoperative chemoradiation therapy. Several case reports have utilized it as the primary therapeutic intervention in high-risk surgical candidates [9], but there is little known regarding what approach increases long-term survival. It can be presumed that for short-term improvements in comfort and symptom management, in the case of our patient, the decision to begin with colostomy diversion, incision and drainage were appropriate at the time.

CONCLUSIONS

Rectal SCC is rarely reported throughout the literature and there is sparse information over standardized diagnostic and treatment algorithms, therefore acute illnesses must be addressed depending on patient presentations.