-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ali Alkhaibary, Sami Khairy, Wael Alshaya, Traumatic thoracolumbar fracture–dislocation in an infant: surgical management using posterior thoracolumbar instrumentation, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 8, August 2020, rjaa279, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa279

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Spinal fracture–dislocation in the infantile population is a rare phenomenon, and its surgical management remains poorly discussed in the literature. This article reports a case of traumatic fracture–dislocation in an infant by outlining the surgical management and extensively reviewing the literature. An 8-month-old girl was involved in a motor vehicle accident and was ejected from the car through the windshield. Radiological imaging demonstrated a complete spinal cord injury at the level of T10 and a three-column fracture of T12-L1, with an evidence of kyphosis measuring 47° at the fracture site. Posterior thoracolumbar instrumentation, using the posterior cervical fixation set, was successfully performed. In experienced neurosurgical centers, posterior thoracolumbar instrumentation can be safely performed in infants with traumatic thoracolumbar fracture–dislocation. This allows for the correction of the kyphotic deformity, facilitation of the rehabilitation course and improvement in the health-related quality of life.

INTRODUCTION

Spinal injuries in the pediatric population range from asymptomatic to high-risk, devastating, injuries [1]. Such unstable injuries are commonly associated with fractures of the thoracolumbar junction and lumbar spine [1]. In children, spinal injuries are mainly caused by high-energy forces as in motor vehicle accidents (MVA) [1]. Spinal fracture–dislocation in the infantile population is exceedingly rare, and its possible surgical management has been rarely reported in the literature [2].

spine radiograph showing a compression fracture at T12 and L1, resulting in gibbus deformity.

Considering the rarity of performing thoracolumbar instrumentation in infants, we herein outline the clinical presentation, radiological findings, surgical intervention and outcome as well as review the pertinent literature of traumatic thoracolumbar fracture–dislocation in an 8-month-old infant managed with posterior thoracolumbar instrumentation and thoracolumbar sacral orthosis (TLSO) brace.

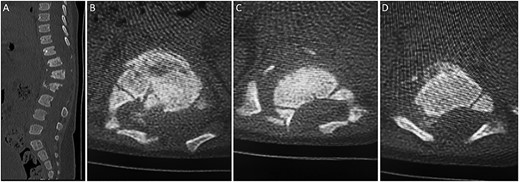

(A) sagittal thoracolumbar CT scan. (B–D) Axial thoracolumbar CT scan. (A-D) There are compression fractures and decreased vertebral body height of T12 and L1 with left pedicle and spinous process fractures. These fractures are associated with bony fragments within the spinal canal causing narrowing of the spinal canal at the same level. There is a nondisplaced fracture at the spinous process of L3 and the left transverse process of T10.

CASE REPORT

Clinical data

An 8-month-old girl, not known to have any medical illness, was involved in a motor vehicle accident (MVA) with her family. The patient was sitting in her mother’s lap in the front seat when she was ejected from the car through the windshield. The patient sustained most injuries among the family members. There was no documented history of loss of consciousness, vomiting or seizures. The patient sustained a complete spinal cord injury (ASIA A) at the level of T12. At that time, she was initially hospitalized at a peripheral medical center for a total of 27 days, and no surgical intervention was performed there. The patient’s general condition was stabilized and then was transferred to our institution, a level-l trauma center, for surgical intervention.

Upon arrival to our hospital, her physical examination revealed that she was vitally stable, conscious and alert. She was active and interactive with no signs of pain, respiratory distress or obvious deformities. The patient was in the ‘frog-like’ position. Power in all lower limb muscle groups was grade 0. Sensation in the lower limbs was absent with a sensory level up to T12. Deep tendon reflexes (DTR) in the lower limbs were absent. Examination of the upper limbs was otherwise grossly intact.

Radiological imaging

A spine radiograph and CT scan (Figs 1 and 2) revealed a three-column fracture of T12-L1 and an L2 body fracture. A multiplanar and multisequential MR images (Fig. 3) of the whole spine were performed utilizing trauma protocol. The images demonstrated narrowing of the spinal canal at the level of thoracolumbar junction secondary to multilevel fractures along with myelomalacia changes involving the lower thoracic cord and conus medullaris. Additionally, the images showed an evidence of kyphosis measuring 47° at the fracture site.

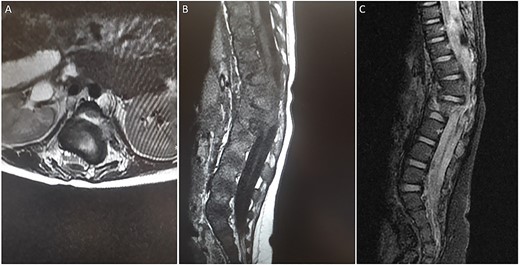

(A) axial T2-weighted MRI. (B) Sagittal T1-weighted MRI (C) Sagittal STIR MRI. (A-C) There are multiple fractures involving the lower thoracic and upper lumbar spine with involvement of the posterior columns and narrowing of the spinal canal. There is a large extramedullary lesion likely representing a small subdural hematoma.

Surgical intervention

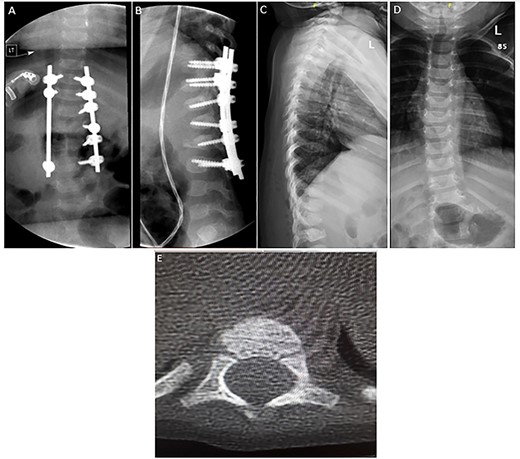

The decision was to perform posterior thoracolumbar instrumentation. The risks and possible complications of the surgery were explained to the family. The aim of the surgery was to correct the kyphotic deformity and facilitate the rehabilitation and nursing course. Posterior thoracolumbar instrumentation using the posterior cervical fixation set was successfully performed (Fig. 4A and B). In the surgery, the facet joint was preserved to prevent fusion and long-term sequelae such as crankshaft deformity. The patient recovered well with no complications after the surgery and was discharged home on a TLSO brace.

(A–B) Spine radiograph demonstrating bilateral paraspinal rods spanning from the level of T10 to L3 transfixed with pedicular screws. The screws and rods are in situ with signs of healed fracture. (C–D) Interval removal of the hardware transfixing the compression fractures of the lower thoracic and upper lumbar vertebrae. (E) Axial CT scan 7 months postoperatively confirming fusion.

Outcome and follow-up

Seven months after the surgery, a follow-up CT and plain radiograph showed healing of the fracture and excellent alignment. The hardware of the posterior thoracolumbar fixation was removed to prevent scoliosis and crankshaft deformity (Fig. 4C–E). The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged with regular clinical and radiological follow-up in the pediatric neurosurgery clinic. Her neurological status remained unchanged, i.e. ASIA A.

DISCUSSION

Posterior instrumentation of traumatic thoracolumbar fracture–dislocations in the infantile age group is rare. A review of the reported data in the literature reveals only one prior case of posterior instrumentation in infancy [2]. We reported an additional case surgically managed at our institution. The patient in the present case is the youngest to be operated on using posterior thoracolumbar instrumentation following thoracolumbar fracture–dislocation.

The application of pedicle screw fixation for fractures was first described by Roy-Camille in 1970 [3–5]. Currently, they are commonly performed for the surgical management in the adult population. However, their application to the pediatric population remains poorly addressed in the literature.

Ruf et al. retrospectively investigated 19 cases of pedicle screws in the management of spinal disorders in young children aged 1–2 years [5]. A total of two patients developed short-term complications, i.e. infection and pedicle fracture [5]. Three patients developed long-term complications. These included failure of screw connections and screw breakage [5]. They have concluded that pedicle screws exerted no effect on the vertebral growth on long-term follow-up in their cohort of patients [5].

Bode et al. reported a case of nonaccidental, i.e. child abuse, traumatic T12-L1 fracture–dislocation in an 8-month-old infant [2]. The patient sustained a T11–T12 cord contusion and was managed surgically with instrumentation with pedicle screws and posterior spinal fusion [2]. Postoperatively, the patient recovered well with no complications and required long-term follow-up visits in the clinic [2].

In the present case, the posterior thoracolumbar instrumentation was removed after 7 months of insertion. This was mainly to prevent crankshaft deformity of the growing, immature, vertebrae and avoid the necessity of subsequent surgeries [6]. In such patients, frequent follow-up visits to the pediatric neurosurgery clinic is essential to confirm the fusion, monitor for any progression of the deformity and assess the long-term outcome.

It is noteworthy to mention that the clinical examination in the general pediatric population can be obscured in cases of thoracolumbar fractures [7]. Additionally, spinal fractures in children are different from those encountered in adults in terms of location, type and their possible sequelae on the vertebral growth [7]. This is mainly due to the unique differences in the anatomical and physiological features of the pediatric spine [7]. In children, the nucleus pulposus is relatively more hydrated, allowing it to absorb pressure effectively [7]. The surfaces of the posterior joints are more horizontal, increasing the risk of anteroposterior displacement of the vertebrae in cases of injuries [7].

CONCLUSION

Comparable to adults, posterior thoracolumbar instrumentation can be safely and effectively performed in infants with traumatic thoracolumbar fracture–dislocation. The neurological outcome of such injuries is dependent upon the severity of the initial spinal cord injury.

FUNDING

None.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.