-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

William T McSweeney, Rasika Hendahewa, Incidental leiomyosarcoma within an ischaemic gut: a review of the management of visceral sarcoma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 2, February 2020, rjaa007, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa007

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Leiomyosarcomas are rare, primary malignancies that can be found in the small bowel in a minority of cases. The management of these visceral sarcomas remains controversial, with surgical resection forming the mainstay, being optimally achieved in a unit familiar with the management of sarcomas. These tumours are difficult to diagnose based on history and are challenging to localize on conventional imaging modalities. We report a case of a 61-year-old female who proceeded to emergent laparotomy with imaging suggestive of small bowel ischaemia secondary to portal venous thrombosis. Incidental leiomyosarcoma was noted on histology and was discussed at local multidisciplinary meeting regarding further management.

INTRODUCTION

Primary tumours of the small bowel are extremely uncommon entities, with leiomyosarcoma being the most common sarcomatous tumour, but falling well short of adenocarcinoma and carcinoid [1]. Historically, these tumours were considered as a similar entity to gastrointestinal stromal tumours, with recent advances in immunohistochemistry allowing differentiation of leiomyosarcoma as a distinct entity. These malignancies are difficult to diagnose based on elements of patient history and are often elusive on conventional diagnostic modalities such as endoscopy and colonoscopy [1]. Effective evaluation and management of patients with suspected leiomyosarcoma hinges upon early referral to specialist sarcoma unit and appropriately planned surgical resection, with limited evidence for chemotherapeutic options [2].

CASE PRESENTATION

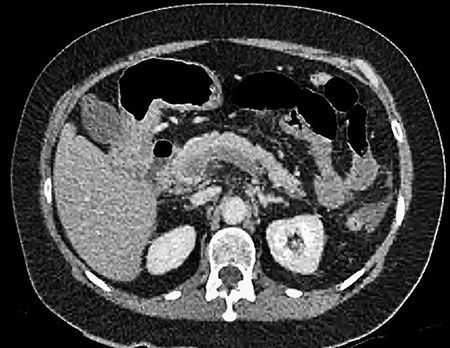

A 61-year-old female presented to a regional hospital with a 3-week history of intermittent diarrhoea, vomiting and generalized abdominal pain. She had a diffusely tender abdomen but was not peritonitic, and was shocked with a heart rate of 110 beats per minute, blood pressure of 89/45 mmHg and was peripherally cool. Her blood tests revealed a lactate of 7.2 mmol/L, which worsened to 7.8 mmol/L during resuscitation with intravenous fluids, and white cell count was 30.9 × 109/L, with an international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.4. She had an acute kidney injury with a creatinine of 119μmol/L and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 43 mL/min/1.73m2. Computed tomography (CT) revealed extensive thickened loops of non-enhancing small bowel with pneumatosis, moderate free fluid and a large splenic infarction. There was extensive thrombosis of the splenic vein and superior mesenteric vein extending into the portal vein to the level of the porta hepatis. Her background history included factor V Leiden and protein S deficiency, for which she had been non-compliant with warfarin during this illness. She had no surgical history (Figs. 1–5).

CT showing multiple thick-walled, non-enhancing loops of small bowel.

CT showing complete occlusion of the portal vein at the level of the porta hepatis.

CT showing an area of splenic infarction due to venous ischaemia.

After initial assessment and fluid resuscitation, she was given broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics and proceeded to emergent laparotomy. Intraoperative findings included an 80-cm segment of ischaemic jejunum, which was resected, with a laparostomy performed and transferred to the ICU. During laparotomy, a small 1.5-cm mass was observed arising from the antimesenteric border of the ischaemic segment, presumed to be a jejunal diverticulum and was included within the specimen. Peritoneal survey revealed splenic infarction but otherwise no other observed organ injury. She was noted to have a dusky-appearing right foot with no palpable peripheral pulse; however, arterial Doppler revealed midperoneal, posterior tibial and anterior tibial arterial stenoses, suggesting ischaemia due to a low-flow state. She was commenced on intravenous heparin. She returned to theatre 36 h later, at which time no further ischaemia was encountered, and anastomosis was performed and the abdomen subsequently closed. She recovered over a period of 1 week and was discharged home on warfarin.

Subsequent pathology revealed an incidental 45-mm, ulcerated spindle cell tumour, with immunohistochemistry in keeping with a smooth muscle tumour. A subsequent second-opinion pathology report supports the diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma of the small bowel, with the tumour being strongly positive for desmin and h-caldesmon and negative for c-kit, DOG-1, S100, MelanA, SOX10, HMB45, CD34, AE1/AE3 and CK8/18. The mitotic index was 9 mitoses/mm2. Staging CT of the chest revealed an 11-mm pretracheal lymph node, which did not show fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avidity on PET scan. Multidisciplinary team discussion recommended only surgical follow-up, with no adjuvant therapy.

DISCUSSION

Primary tumours of the small bowel are extremely rare and comprise only 5% of all gastrointestinal tract cancers, with an incidence of only 22.7 cases per million. Only 1.2% of these are sarcomas [1]. Furthermore, leiomyosarcoma is an exceedingly rare malignancy of the small bowel, falling well below carcinoid and adenocarcinomas in terms of incidence. These tumours are the most common of sarcomas, but there remains only a small number of case reports of primary small bowel leiomyosarcoma. Such is the rarity of these tumours that a meta-analysis of English publications over a 10-year period only found 26 reported cases, while a retrospective analysis of 252 gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumours confirmed only three cases [3, 4]. These tumours are differentiated from gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) by the lack of c-KIT, DOG1 and CD34 staining, as well as positivity for markers like desmin and h-caldesmon [1]. They remain a very difficult entity to diagnose, often presenting late or with metastases, as traditional modalities such as colonoscopy and endoscopy, which may be employed for symptoms such as weight loss, constipation and bleeding per rectum, may miss these tumours. Other imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance enterography, CT colonography or capsule endoscopy may need to be employed. These cancers tend to metastasize via haematogenous spread, especially when larger than 5 cm. They do so to the liver, followed by other GI tract organs or the lungs. Other modalities of spread include lymphatic or peritoneal.

The prognosis of these tumours is generally poor, with a median survival reported to be 12 months and a 5-year survival when the tumour is over 5 cm of 5–27%. Tumour size and histological grade are independent prognostic factors for 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS) [1]. A large review of 14,253 small bowel tumours revealed a 5-year DSS of 38.9%, with a median survival of 34.1 months. Patient age, sex, tumour size, grade, histological subtype, nodal status and whether or not surgery was performed were significantly correlated with DSS [1]. Of note, leiomyosarcoma histology was favourable in prognostication.

There is currently no universally accepted histological grading system; however, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) system or the French Federation Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer (FNCLCC) are both commonly used [5]. The NCI system is based on evaluation of tumour histology, location and amount of tumour necrosis, while FNCLCC is based on tumour differentiation, number of mitotic figures per 10 high-powered fields and degree of tumour necrosis [5, 6]. A comparative study of the two grading systems suggested that the FNCLCC had a slightly increased ability to prognosticate in terms of distant metastasis development and mortality [5].

Staging of sarcomas is generally limited in relevance and is widely cited as needing improvement [7]. The ESMO-EURACAN guidelines recommend the use of the Union for International Cancer Control stage classification system, which makes a specific mention of the importance of malignancy grade, as well as size and depth. They define tumour ‘T’ staging as confined to a single organ (T1), invading serosa or visceral peritoneum (T2a), microscopic extension beyond serosa (T2b), invasion into another organ or macroscopic extension beyond serosa (T3), or multifocal tumour (T4) [7].

The guidelines from the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual [8] differ in defining the tumour, node, metastases (TNM) staging of soft-tissue sarcomas. These define a ‘T1’ lesion as <5 cm in size, while >5 cm is nominally defined as ‘T2’. The designation of the suffix ‘a’ or ‘b’ depends on whether it is a superficial or deep lesion, of which intra-abdominal is defined by convention as deep. Regional lymph node metastases are scored as either ‘N0’ if absent or ‘N1’ if present, as are distant metastases. Importantly, they recommend histological grading of sarcomas as paramount and recommend the use of the FNCLCC grading system owing to ease of use and reproducibility, as well as slightly superior performance. The scoring system as outlined earlier produces a grade 1, 2 or 3.

The local guidelines to the authors are those of the Clinical practice guidelines for the management of adult onset sarcoma [2]. Of key importance, these patients should be referred to a specialist sarcoma unit when this diagnosis is suspected. Any lesion greater than 5 cm, deep to or attached to fascia, should be considered a sarcoma until it is proven otherwise. These guidelines would suggest that CT is usually adequate for the assessment of abdomino-pelvic masses and that CT chest is mandatory to assess for metastatic disease. PET-CT is also useful in soft tissue sarcomas and is superior to whole body bone scan. In the case of a primary diagnosis of soft tissue sarcoma outside of a sarcoma unit, a referral to an expert pathologist for second opinion should be undertaken. After a suspicion is formed, referral to a specialist unit is also suggested to reduce incomplete excision, reoperation, recurrence and to improve survival [2].

When planning surgery, a biopsy should be performed preferably under CT guidance to facilitate determination of the track of biopsy and to confirm that the biopsy is representative of the lesion. Once surgery is undertaken, local recurrence is related to the adequacy of surgical margins, and wide margins should be sought here, except when planned adjuvant chemotherapy/radiotherapy is employed [1].

After surgery, the use of post-operative chemotherapy in adult-type soft tissue sarcomas is not the current standard of care neither it is a pre-operative chemotherapy. An initial meta-analysis by Pervaiz et al. [9] found a marginal efficacy of chemotherapy in localized resectable soft-tissue sarcoma with respect to local and distant recurrence, overall recurrence and survival. Furthermore, the benefits of a doxorubicin-base regimen are improved with the addition of ifosfamide but should be considered with regard to toxicities. However, a subsequent multicentre randomized controlled trial by Woll et al. [10] found that adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin and ifosfamide showed no benefit in relapse-free survival or overall survival [2]. This is the subject of continued research, and these patients should be referred for clinical trial participation if considered for chemotherapy.

In terms of follow-up for these patients, there are a number of recommendations. Where the primary site is difficult to examine, including the retroperitoneum or visceral primary as in this case, routine imaging may be appropriate. Recommended follow-up intervals are three to four months for the first and second years after diagnosis, then six months in the third and fourth years and annually thereafter [2]. There is no universally accepted stopping point. For patients that are considered to be potentially suitable for pulmonary metastasis resection in terms of surgical fitness and prognosis, low-dose non-contrast CT chest is the modality of choice for ongoing surveillance.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

W.T.M contributed to the conception and design of the study. R.H contributed to the critical revision of the concept and study. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

An informed consent was obtained from the patient.