-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hefzi Alratrout, Mahery Raharimanantsoa, Cecile Brigand, Sébastien Moliere, Yaniv Berdugo, Julien Uzan, Serge Rohr, Biliary pancreatitis in a duplicate gallbladder: a case report and review of literature, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 5, May 2018, rjy112, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy112

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Duplicated gallbladder is a rare congenital anomaly that require special attentions due to its clinical, surgical and diagnostic difficulties. We present a case of a 39-year-old female patient with a duplicated gallbladder who presented with an acute biliary pancreatitis, a case to our knowledge is the first in the literature. A double gallbladder in an abdominal ultrasonography was doubtful, thus a computed tomography scan, a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography were done that confirmed the double gallbladder. A laparoscopic cholecystectomy with an intraoperative cholangiography was performed safely two months after the acute attack. The histopathological report revealed a Y-shaped type 1 double gallbladder according to the Harlaftis et al. classification.

INTRODUCTION

Double gallbladder is a rare congenital variation, with an incidence of 1:4000, twice high in women as in men [1]. An autopsy done by Blasius reported the first accessory gallbladder in 1674. However, it was not until 1911 that Sherren documented the first ever double gallbladder in a living patient [2]. Accurate preoperative diagnosing is crucial, double gallbladder can be missed during preoperative imaging [3]. Abdominal ultrasonography (US) (which is operator dependent) and computed tomography (CT) scans may not give us sufficient visualization of the biliary anatomy to detect theses kind of anomalies [3]. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) has a superior diagnostic capability than US. However, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is considered the gold standard for diagnosing these rare anomalies. When confronting an accessory gallbladder intraoperatively, both gallbladders should be removed to avoid complications [3]. Reinisch et al. [4] re-operated a 73-year-old patient 17 years after his cholecystectomy due to an acute cholecystitis in his accessory gallbladder which was not detected during the first surgery.

CASE REPORT

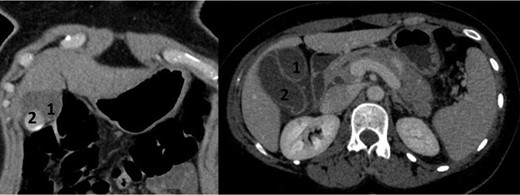

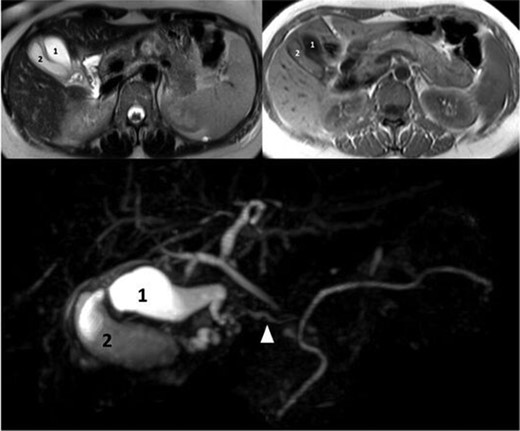

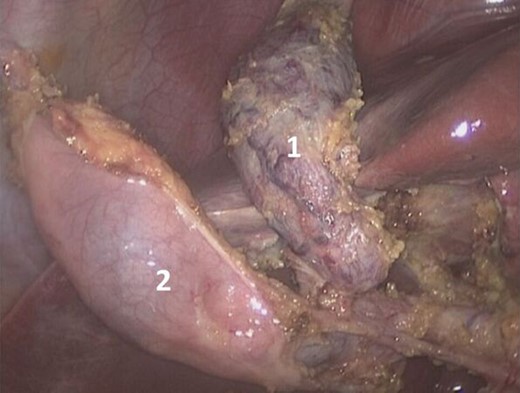

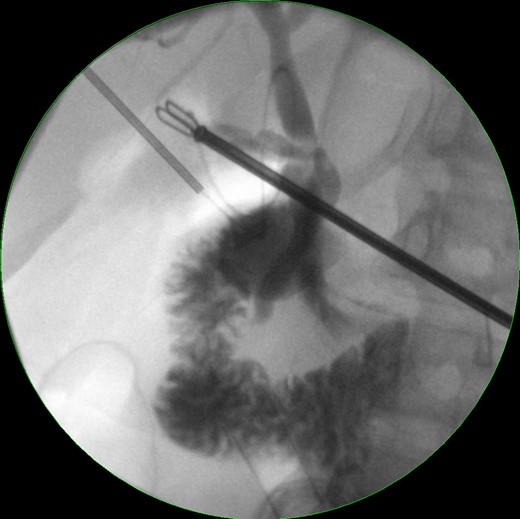

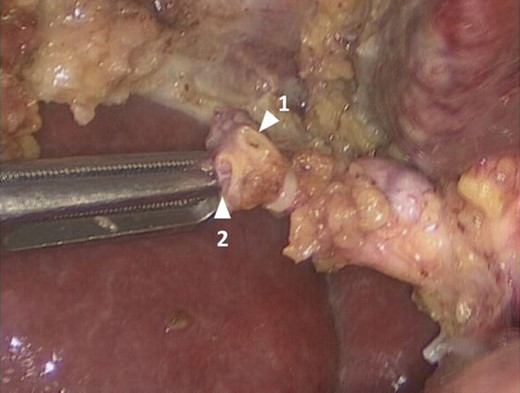

A 39-year-old healthy female, presented to our emergency department due to abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. She was febrile, with a tender right hypochondrial and epigastric region. Her laboratory results showed a normal complete blood count and C-reactive protein level. Liver function test showed an elevation in total bilirubin at: 42 mmol/L, direct bilirubin level at: 29 mmol/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) level at :160 U/L and Lipase level at: 34 000 U/L. An abdominal US showed two separate gallbladders with a sludge (Fig. 1). Abdominal CT scan showed a Balthazar grade C pancreatitis and confirmed the presence of a double gallbladder (Fig. 2). An MRCP confirmed the double gallbladder (Fig. 3). An ERCP was performed with evacuation of biliary debris in the common bile duct (CBD). The patient was discharged home after appropriate medical treatment a couple of days later with a full normal liver function test. Two months later, a laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed where the two gallbladders were dissected with a dome-down technique, from the gallbladder fundus towards the neck (Fig. 4), the cystic duct and artery were identified. An intraoperative cholangiography was performed which showed patent intrahepatic ducts, cystic and CBD (Fig. 5). A Hem-o-lock® clip (WECK Closure System; Teleflex Inc., Morrisville, NC, USA) was then placed on the main cystic duct (Fig. 6), and another Hem-o-lock® clip was placed on the cystic artery. Figure 7 showing the gross specimen. The final histopathology report concluded two separate gallbladders, each having its own cystic duct, with both cystic ducts joining to form a main cystic duct.

Ultrasonography showing the two distinct gallbladders (1 and 2) with sludge in one of them (arrowhead).

CT scan in frontal and axial slices showing two distinct gallbladders (1 and 2) with cholelithiasus in one of them.

MRI with T2-weighted, T1-weighted images and MRCP showing two distinct gallbladders and one main cystic duct (arrowhead).

Laparoscopic view showing two separate cystic ducts joining to form one main cystic duct, with a clip on it.

DISCUSSION

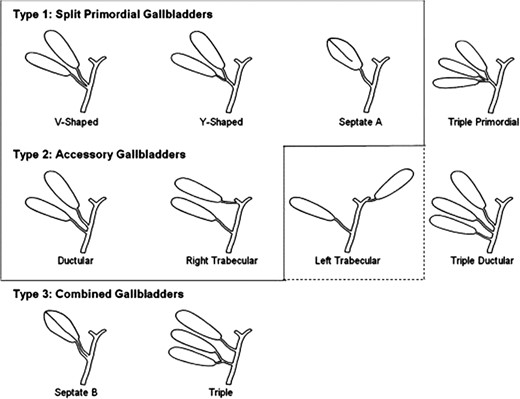

During the seventh week of gestation, the gallbladder arises from the caudal aspect of the hepatic diverticulum which is a ventral outgrowth of the human foregut. The duplication of the gallbladder usually occurs due to outpouching from the extrahepatic biliary system during the fifth and sixth weeks of gestation. If those outpouchings persist, they form an accessory gallbladder [5]. The anatomical variations of accessory gallbladders have been classified by several authors, Boyden being the first in 1929, where he reported 20 cases of double gallbladder in the literature from 1674 to 1929 [6]. He classified these anomalies into: vesica fellea divisa (bi-lobed gallbladder with a single cystic duct), and vesica fellea duplex (true gallbladder duplication). The latter being divided into Y-shaped (two cystic ducts uniting before entering the CBD); and H-shaped (two cystic ducts enter separately into the CBD) duplication. In 1977, Harlaftis et al. [5] modified the classification by describing three main types of gallbladder duplication based on embryogenesis (Fig. 8). Type 1, or split primordial group, has one single cystic duct draining in the CBD, it’s subdivided into septated, V-shaped (two gallbladders joining at the neck level), or Y-shaped (two separate cystic ducts joining to form one single cystic duct that drains into the CBD). Type 2, or the accessory gallbladder group, has more than one cystic duct draining into the CBD. H or Ductular type and right or left hepatic duct trabecular type. In the H or Ductular type, the accessory cystic duct connects to the CBD. In the trabecular type the accessory cystic duct connects to the right hepatic duct. Type 3 accessory gallbladder includes rare anomalies that do not fit either type 1 nor type 2 (e.g. triple gallbladder). A modified Harlaftis classification has been reported in the literature describing a left trabecular variant to type 2 classification [7] (Fig. 8). In our case, the double gallbladder was a Y-shaped type 1. Any complications that can occur in a single gallbladder may occur in a double gallbladder [8, 9]. The most common being stone formation. Preoperative diagnosis of double gallbladder is important to prevent possible surgical complications. However, only one half of all cases of double gallbladders are diagnosed preoperatively.When a double gallbladder is suspected, MRCP, allows visualization of the two independent gallbladders and, as the case may be, the presence of separate cystic ducts. We highly recommend intraoperative cholangiography that provides an outline to the biliary anatomy and reduces the risk of injury to the biliary tree. Some surgeons have recommended open surgery in case of accessory gallbladder anomalies, especially in type 2 double gallbladder [10], because the risk of injuring the CBD or the right hepatic artery during dissection is higher. Yet, we believe that accurate preoperative planning, makes the laparoscopic approach by an experienced surgeon a safe option.

CONCLUSION

Double gallbladder is a challenging rare congenital anomaly. Accurate preoperative imaging and high index of suspicion are required in order to avoid surgical complications. We recommend these cases to be managed by an experienced laparoscopic surgeon or a hepatobiliary surgeon.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Hefzi Alratrout and Mahery Raharimanantsoa Contributed equally to the work.

- congenital abnormality

- computed tomography

- endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- attention

- surgical procedures, operative

- diagnosis

- gallbladder

- laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

- pancreatitis, biliary

- abdominal ultrasonography

- cholangiogram, intraoperative

- gallbladder, accessory